Vernon Handley Records Bax in Manchester – A Session Report by Richard R. Adams

Vernon Handley Records Bax in Manchester

THE SIR ARNOLD BAX WEB SITE

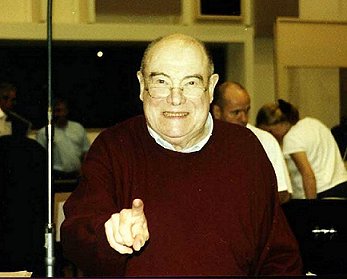

Vernon Handley Conducting the BBC Philharmonic in August 2003

Session Report by Richard R. Adams

Vernon Handley’s mad dash to record the Bax symphonies for Chandos in time for an October 2003 release date continued in August with the recording of the Fifth and Seventh Symphonies in Manchester. I had the privilege of being able to attend the sessions and witness the extraordinary playing of the BBC Philharmonic as well as the technical brilliance of the BBC Manchester recording team who are producing and engineering the recordings for Chandos. Most importantly, I was able to watch first hand the mastery of a great conductor in music that he has known, loved and performed all of his life.

Like most Baxians, I have been waiting for a Handley-led cycle of the symphonies ever since I first became familiar with the composer. Almost intuitively I could tell that earlier efforts to record the symphonies, whatever their merits, fell short of what was possible in this music. My suspicions were confirmed when I first heard Handley’s broadcast performances of the Bax symphonies from the 1970s and 80s. Despite the less then perfect sound and often uneven playing, the interpretations revealed what I had missed in most other performances and that was a feeling of total conviction as well as a rock-solid command of the music’s architectural design. Where other conductors sounded timid and reluctant to follow Bax’s demands for sharp accents, sudden attacks and often very fast tempos, Handley was brave enough to take Bax at his word and as a result his performances revealed an icy brilliance and hard core that related these symphonies more to the elemental sound world of Nordic and Russian music then the more introverted romanticism of Bax’s British contemporaries. Handley’s Bax is a good deal leaner and more austere than what we’ve heard before and those who were raised on Bryden Thomson’s Chandos cycle are in for quite a shock.

Admittedly, I was a little worried because most of the Handley/Bax symphony recordings that I have heard are more than 30-years old and I wondered if the great Maestro’s conducting may have mellowed a little in the passing years. After all, that was true of his great mentor, Sir Adrian Boult, whose recordings from the 1940s and 50s are a good deal more energetic than those he made during his Indian summer for EMI and Lyrita. Just compare his earlier Decca Tintagel with his Lyrita account and you’ll see what I mean. I really wasn’t sure what to expect when I arrived at the BBC Manchester Studios on Tuesday Morning August 5, 2003. I entered into the huge auditorium where I found the players of the BBC Philharmonic going over their parts. Maestro Handley was on the podium talking to the players but as soon as he saw me he stepped off the podium and came over to welcome me to the sessions. He appeared a little tired but he was full of enthusiasm for the work that was ahead of him and he informed me that he had heard the edits of the previous recordings in this cycle and he said he was very pleased with the results. All the time he was speaking I was thinking how amazing it was for him to have bothered to come over and welcome me knowing the kind of pressure he was under but that kind of graciousness is wholly characteristic of the man. His manner with the orchestra, the production team and the few guests who had been invited to attend the sessions was always warm and affectionate even during those few moments when tensions were high and things weren’t going as smoothly as they should. Never once did I see him lose his temper or the control of all that was going on around him even though he had a Herculean task to achieve – the recording of two symphonies and an overture in just four days. I understand now why orchestral players love him so deeply. In fact, once while I was speaking to him, a string player came up to him and told him how much she enjoyed working with him and added that she wished he would conduct the orchestra more often. This was the typical response of just about every player I spoke with — they all expressed their admiration for “Tod” even those who, remarkably(!), don’t share his enthusiasm for Bax’s music.

As the rehearsal was about to begin, I quickly took my place on the seats immediately in front of the orchestra. I was soon joined by my good friend Graham Parlett, the eminent Bax musicologist and frequent guest to these sessions. He is an indispensable part of the team due to his encyclopedic knowledge of Bax’s music and manuscripts. Bax’s printed scores are full of errors and Graham is the authority who is called upon whenever there is a question about the parts. Graham and I sat together, both with our scores open and ready to follow along but as Handley began his rehearsal, both of us put down our scores and focused all attention on what was taking place in front of us. While Handley is now in his early 70s, you would never guess that from his energetic conducting. His opening tempo for the first movement of the Fifth Symphony was very brisk – much more so even than his earlier broadcast performance. He played through most of the first movement almost without a stop and at several points throughout I shook my head in disbelief that the BBC Philharmonic could sight read so well. As a result of Handley’s vital conducting, the music sounded incredibly tight and flowed more naturally then is sometimes the case in this movement. Whatever concerns I had that Handley’s conducting of Bax may have mellowed with the years was immediately dispelled. In fact, the opposite was true and I was hearing Bax in a manner unlike I had ever heard before.

Graham Parlett and Vernon Handley review a problem in the score.

The rehearsals were broken up into three-hour segments with one or two short breaks within. Handley and the orchestra ran through the entire Fifth Symphony, the raucous Rogue’s Comedy Overture and the first movement of the Seventh Symphony the first day. The second day began with another rehearsal during which the orchestra played through all three movements of the Seventh Symphony. Handley appeared even more energetic and youthful than he had the first day. The music appeared to be revitalizing him and the orchestra was responding with even more incisive playing. The fact that they were working from handwritten scores in the Seventh Symphony and Overture only confirmed the extraordinary abilities of these players. Again the tempos that Handley adopted for the Seventh Symphony were faster than any I’d heard before. In fact, I thought the playing was almost too quick, especially in the moody lento middle movement which seemed to lose some of its atmosphere being driven at such an urgent pace. The recording of the Seventh Symphony began that afternoon and Graham and I were invited into the control booth with engineer Stephen Rinker and producers Brian Pidgeon and Mike George. Not being able to see the orchestra very well from where I was sitting, I decided to follow along with my score while Handley began recording the first movement. What I noticed immediately was the scrupulous attention to detail as well as the slower tempos he adopted from those he had taken in the rehearsal. Now Handley was allowing for more romantic phrasing and much slower tempos in the quieter passages. Handley later told me that he deliberately adopts faster tempos when first rehearsing a work in order to allow the orchestra to later “relax” into the music. Still, the overall tempos for the recording were on the urgent side and Handley revealed the Seventh Symphony to be a much more dramatic and even conflicted symphony than what I had previously believed. Handley’s recording will prove that the Seventh Symphony in no way demonstrates a falling off of inspiration on Bax’s part. In fact, as conducted by Handley, it has to be ranked among his very greatest works.

Special mention must be made of the BBC Philharmonic’s leader Yuri Torchinsky’s many solos throughout the work – especially the very tricky “In Legendary Mood” section of the middle movement. In some of the other recordings, the violin solos sound perfunctory but here Yuri really invested himself in the music and managed to convey its strange atmosphere with playing that was as delicate as it was virtuosic. Indeed, the final recording of that middle movement was a revelation – more impassioned and cohesive than any other recording I’ve heard including the very fine Leppard account on Lyrita. Handley’s tempos for the last movement of the Seventh were the most urgent of all yet all the variations were shaped with tremendous character and Handley drew extraordinary playing from the winds in particular. The whole movement seemed to rush along until the transition into the epilogue where Handley gradually allowed the momentum to subside and relax into the most beautiful performance of the epilogue that I’ve yet heard. Handley believes the epilogue to be “Bax’s Farewell” and he inspired the orchestra to play with extreme attention to dynamics and it was here that Handley allowed for a little more rubato. I know I was fighting back tears at those closing pages and I suspect many will do the same when they hear this music played from the CD.

Thursday and Friday were spent recording the Rogue’s Comedy Overture and Fifth Symphony. The overture is a very difficult work and more time was taken to get this one overture recorded then for any of the individual movements of the symphonies. All involved in these productions are obsessive perfectionists and no slip-shod playing was allowed – not that that’s ever a problem with the BBC Philharmonic! And as I said before, for a man of 72-years, Handley has extraordinary energy. It was remarkable to watch him record a section and then practically sprint into the recording studio to hear the playback – usually followed by several players from the orchestra. At this point, Handley and Mike George would then carefully review what had just been recorded, notate on the score what errors there were and then Handley would go out and record another take. Their preference was to record complete takes of entire movements and then patch in only those few sections that needed fixing. With a very fixed recording schedule to observe, this process can be quite tense and I could see that Handley was under a lot of pressure to get a lot of music recorded in a very short period of time. It helped that all involved were giving their all, especially the orchestra and this was due in large part to Handley’s ability to create a joyful working atmosphere through the use of his razor-sharp use of humor. All were relieved when the overture was recorded and equally surprised that a work, virtually unplayed since its premiere (Handley actually recorded this work once before for Lyrita but that performance has never been issued) could turn out to be so infectiously enjoyable. It will be a pleasant discovery for all Baxians.

The Fifth Symphony was recorded last and again Handley managed to secure a performance that is more urgent and concentrated than any I’ve heard before. I believe it will be one of the highlights of the set. Handley was particularly pleased with his handling of the tricky transition into the epilogue of the final movement of the Fifth Symphony. This section has confounded just about every other conductor who has recorded the work and Handley navigates his way through the epilogue to the coda without having to resort to any of the awkward tempo shifts that can cause the music to bog down. Handley said that his interpretation of the Fifth Symphony has probably changed the most over the years and he now feels that he has managed to get it right. All who witnessed the recording were in agreement.

During the breaks in the recording of the Fifth Symphony, I spoke with several players in the orchestra as well as the recording engineer, Stephen Rinker, and executive producer, Brian Pidgeon, whom we all have to thank for this project taking place for it was Brian who first invited Handley to record the Third Symphony and Tintagel with the BBC Philharmonic in January 2002. Those recordings were originally intended to be released as a BBC Music Magazine companion disc but after hearing the brilliance of those performances, Pidgeon decided to invite Handley to record all the symphonies for BBC Radio 3. He said he knew how eager Handley was to do the entire set and here was an opportunity to get all the Bax symphonies recorded in time for the 50th anniversary of Bax’s death. Because the BBC Philharmonic has such a close relationship with Chandos, he approached that label with a proposal to release the recordings commercially. To his great surprise, Chandos agreed. This was a remarkable turn of events due to the fact that Chandos already has the Thomson Bax cycle in its archives but evidently they too were impressed by the performance of the Handley Bax Third and agreed it would be great to release a new set of symphonies from Bax’s great interpreter. Pidgeon said Radio 3 will broadcast the performances the first week of October during their afternoon orchestra program. Handley’s public performance of the First and Sixth Symphonies in early September will be broadcast that same week as well. Pidgeon has also produced two other forthcoming Bax discs for Chandos including the complete score to Oliver Twist, conducted by Rumon Gamba and a disc of Bax choral works for orchestra including To the Name Above Every Name and St. Patrick’s Breastplate with Martyn Brabbins conducting, all with the BBC Philharmonic. These discs will also be released this autumn.

During the breaks in the recording of the Fifth Symphony, I spoke with several players in the orchestra as well as the recording engineer, Stephen Rinker, and executive producer, Brian Pidgeon, whom we all have to thank for this project taking place for it was Brian who first invited Handley to record the Third Symphony and Tintagel with the BBC Philharmonic in January 2002. Those recordings were originally intended to be released as a BBC Music Magazine companion disc but after hearing the brilliance of those performances, Pidgeon decided to invite Handley to record all the symphonies for BBC Radio 3. He said he knew how eager Handley was to do the entire set and here was an opportunity to get all the Bax symphonies recorded in time for the 50th anniversary of Bax’s death. Because the BBC Philharmonic has such a close relationship with Chandos, he approached that label with a proposal to release the recordings commercially. To his great surprise, Chandos agreed. This was a remarkable turn of events due to the fact that Chandos already has the Thomson Bax cycle in its archives but evidently they too were impressed by the performance of the Handley Bax Third and agreed it would be great to release a new set of symphonies from Bax’s great interpreter. Pidgeon said Radio 3 will broadcast the performances the first week of October during their afternoon orchestra program. Handley’s public performance of the First and Sixth Symphonies in early September will be broadcast that same week as well. Pidgeon has also produced two other forthcoming Bax discs for Chandos including the complete score to Oliver Twist, conducted by Rumon Gamba and a disc of Bax choral works for orchestra including To the Name Above Every Name and St. Patrick’s Breastplate with Martyn Brabbins conducting, all with the BBC Philharmonic. These discs will also be released this autumn.

John Bradbury, principal clarinet for the BBC Philharmonic, has been a Bax admirer ever since he first played the Bax Clarinet Sonata while he was in college. He can be heard as the solo clarinet in the Chandos recording of Concertante for Three Solo Wind Instruments, conducted by Martyn Brabbins. Bradbury is drawn to Bax partially because of the way he writes for his instrument. “I think Bax must have liked the clarinet,” he says. “Technically, his writing is very difficult especially in the fast passage work but the many slow solos are very rewarding to play. I also love his sense of rhythm and he writes a lot in the low register, which is a sign of a composer who really knows and is exploring the instrument.” I asked John how the orchestra was responding to playing the music. “Well,” he said, “when you record two symphonies in a row like what we are doing this week, the process can be quite tiring. But it is a very exciting project and the orchestra is realizing that — especially as it’s being done with Tod.” I then asked John what makes Handley’s Bax so remarkable. “Well, the music is obviously completely within him and he drives it when it could get stuck or become too sentimental and that marks him out from any other conductor of Bax that I’ve worked with. He knows the music phenomenally well and his enthusiasm for it is quite infectious.”

David Chatwin is the principal bassoon of the BBC Philharmonic and his experience with Bax began in the late 1960s when he played the Garden of Fand in the Royal College of Music Orchestra conducted by Handley. “I just fell for that music hook, line and sinker partially because the bassoon parts are so well written and I could also see that the orchestration was superior to so much other English music,” he said. “After that experience of playing Fand, I went out and photo copied every single Bax score I could find and taped everything of his that came on the radio. I just adored that music.” I asked Chatwin, who incidentally conducted the premiere performance of Cathaleen-ni- Hoolihan in 1970, what it feels like to be taking part in this project. “It’s absolutely amazing – especially to be able to do all the symphonies and I love the sound that Handley is getting from this orchestra in Bax’s music. He has lived and breathed these symphonies all his life and there is still so much that he wants to put into the music. He still feels so much passion for it.” I asked David how the orchestra seems to be responding to playing these scores and he said that has been varied. “I think some people are upset because the scores are very hard to play with lots of changes in key and some of the parts are very hard to read. The parts for the Seventh are very badly written out and I suppose some people just find it embarrassing to be playing music by an English composer that is passionate and wears its heart on its sleeve – some people have a real problem with that.”

The sound engineer, Stephen Rinker, is also a devout Baxian and has engineered all the BBC Philharmonic Bax recordings. He says he got to know most of Bax’s scores from the earlier Chandos recordings with Bryden Thomson although his very first experience with Bax came from sight-reading the opening bassoon part in Bax’s Third Symphony when he played in the London Repertoire Orchestra conducted by Ruth Gipps, whom he says was a great Bax enthusiast. I asked Stephen how he would compare his engineering with that of the earlier Chandos set. “I think some of the earlier Chandos Bax recordings were overly reverberant and processed and of course they were all done at various venues. Our recordings are all done in the studio and what we’re trying to do is reflect Tod’s approach and get all that amazing detail that he is drawing from the orchestra. Bax was an amazing orchestrator and we’re simply trying to do justice to his music. We’re all committed to do the best by Bax because this is such an important project.” I asked Stephen what it is like to work with Handley. “He’s been a musical hero of mine for years so it’s a fantastic opportunity to do all these symphonies with him.”

When the sessions ended on the 8th of August, the orchestra began a much-deserved three week holiday. For the production team, on the other hand, the arduous process of editing the recordings was still before them. In early September, the same production team, Handley and the BBC Philharmonic reunited to record the last two symphonies in this project, the First and the Sixth. All will be edited and then prepared by Chandos for an October release date. Everyone involved in this project seems to understand that this set is being more keenly awaited than just about any other project they’ve been involved with and because of that, every effort has been made to assure its success. For Handley, these recordings are the culmination of a life-long devotion to Bax’s music and for the rest of us, they will likely become the benchmark by which all future recordings of Bax’s symphonies will be judged.

Photos by Richard R. Adams – Photo Editor Christopher Webber

Copyright © Richard R. Adams

POST NOTE: Vernon Handley’s recordings of the Bax Symphonies won the Gramophone Award for Best Orchestral Album for 2003.