Richard R. Adams interviews David Owen Norris

Editor’s Note: David Owen Norris is one of the best-known and beloved figures in British music today. He is a pianist, broadcaster and composer as well as Professor of Musical Performance at the University of Southampton, Visiting Professor at the Royal College of Music and at the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester, a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Music, a Fellow of the Royal College of Organists, and an Honorary Fellow of Keble College, Oxford.

Editor’s Note: David Owen Norris is one of the best-known and beloved figures in British music today. He is a pianist, broadcaster and composer as well as Professor of Musical Performance at the University of Southampton, Visiting Professor at the Royal College of Music and at the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester, a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Music, a Fellow of the Royal College of Organists, and an Honorary Fellow of Keble College, Oxford.

David Owen Norris was the first winner of the Gilmore Artist Award and has played concertos all over North America and Australia and in the BBC Proms. Solo recitals, all over the world, have particularly featured the music of Brahms, Schubert, Poulenc, Bax & Elgar. Lately, David Owen Norris’ own compositions have been gaining a large following and critical acclaim including the oratorio Prayerbook, the Piano Concerto in C and the Symphony. Two large-scale works appear in 2015: Turning Points, a celebration of democracy supported financially by the Agincourt600 Committee, and HengeMusic a multi-media piece for organ and saxophone quartet with film and poetry, supported by Arts Council England. David Owen Norris frequently performs the music of Bax and this October will be premiering several works at the Guildhall Art Gallery..

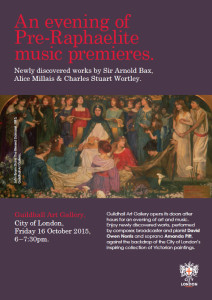

Richard Adams (RA): As adventurous programs go, your October-scheduled “An Evening of Pre-Raphaelite Music Premieres” pretty much carries off all honors as you’re presenting three Bax premieres as well as unknown songs by Alice Millais and her husband Charles Stuart Wortley. How did you discover these works and what prompted you to present them in one program?

Richard Adams (RA): As adventurous programs go, your October-scheduled “An Evening of Pre-Raphaelite Music Premieres” pretty much carries off all honors as you’re presenting three Bax premieres as well as unknown songs by Alice Millais and her husband Charles Stuart Wortley. How did you discover these works and what prompted you to present them in one program?

David Owen Norris (DON): I’ve been giving recitals that blend music & pictures for years – and not just song recitals. Most recently I’ve created movies that accompany two suites of piano portraits. For Sir Hubert Parry’s Shulbrede Tunes, a series of musical pictures of his daughter Dolly, her family and the beautiful mediaeval house they lived in, Shulbrede Priory, I filmed the house (where Parry’s great-grand-daughter now lives), its gardens, and many items of Parry memorabilia, blending them into short films that match the shapes of the ten individual pieces. Just last week I performed them to a select audience in the Priory itself, on Sir Hubert’s own piano – a wonderful experience. Poulenc’s >Les soirées de Nazelles is a series of portraits of people we can know only through the composer’s ironic titles – Old but Spry,Heart on Sleeve, and so on. I asked a famous political cartoonist, Martin Rowson, to listen to me playing each portrait until he ‘saw’ the characters, and as he proceeded to draw them, I filmed him in the act. For performance, we simply speed up the film so each portrait is painted in the time it takes to play the piece. At the first performance, Martin delighted the audience by painting an encore live on stage, to Poulenc’s Valse-Caprice sur le nom de Bach (At present I’m developing the technical discoveries I made in these projects by composing a piece of my own for organ & saxophone quartet, to accompany films of a Neolithic henge with a ruined Norman church at its centre, and, at its entrance, a yew grove still functioning as a place of prayer, as the ribbons, messages, photos and treasures hung about the boughs firmly attest.HengeMusic it’s called, and it’s a homage to the great tradition of English landscape music. The world premiere will be in Keble College Chapel in Oxford on October 29 this year.)

Messing about with pictures all the time, then, meant that Amanda Pitt and I were the ones who were asked to provide a recital for the opening of the important re-hang of the Victorian collection at the City of London’s wonderful Guildhall Art Gallery back in January. One of the pictures is Byam Shaw’s Blessed Damozel, and when I mentioned this in conversation with my friend Lewis Foreman (the great Bax-man, as readers of this website will know very well), Lewis bethought himself of Bax’s as yet unperformed recitation to Rossetti’s great poem. Turned out there was an unperformed William Morris song too, as well as the little-performed published one. Pre-Raphaelites everywhere!

That chat with Lewis reminded me of an interesting folder of tatty old songs someone had given me after a concert in Southampton. John Everett Millais was born in Southampton, which may have had some bearing on the astounding fact that the folder contained a song by – Alice Millais! The painter’s daughter. Now, I’m a devout Elgarian, so Alice Millais, Elgar’s windflower, is a very familiar figure. My double CD recorded on Elgar’s own piano includes the first version of the tune that became the Cello Concerto, which he sent to Alice with the title ‘?’, and a note ‘for a good Windflower’. Back in 2007, in an Oxford magazine, The Owl, I published an article that brought together for the first time paintings by Vicat-Cole (Elgar’s landlord at the Brinkwells cottage) that show the idyllic garden studio (since removed) where Elgar did his late composing, and Elgar’s favourite painting, Millais’ Lorenzo & Isabella, along with Elgar’s letters about it to Alice. And it was I who recorded the re-construction of the fragmentary Piano Concerto Elgar wrote with Alice in mind.

But despite all that, I had no idea at all that Alice was a composer. A few days searching brought more surprises. There was another song, to words by – Christina Rossetti! And, very surprising indeed, there were two songs by her husband, a Member of Parliament and later a Baron, no less, Charles Stuart Wortley. You know, it’s strange how you find things out. Just the other day, popping in to the Royal Academy of Music (the new building of 1911, not the one Bax knew), I bumped into the Curator, Janet Snowman, and in the course of our casual conversation I suddenly learned that a picture hanging in the Duke’s Hall, a picture I know well from my own twenty continuous years (1971-1990) at the Academy as student and professor, was painted by Charles’s brother Archibald, who was – J.E. Millais’ only pupil! You simply couldn’t make this stuff up. (Just to tie that one up, Archibald married Nellie Bromley, who was the first Plaintiff in Gilbert & Sullivan’s Trial by Jury. So Alice suddenly becomes a link between Elgar & Sullivan.)

Well, the January performance was only a brief affair amongst the speeches, so we decided to make a special occasion later in the year for all these remarkable premieres. October 16th2016. The reason to put them all in one programme is that the opportunity to perform Alice’s songs in the presence of some of her father’s greatest pictures (including the famous ‘Sermon’ pictures of her sister Effie), and to recite The Blessed Damozelin the presence of the Blessed Damozel herself, comes but rarely.

RA: What can the listener attending your recital expect to experience at the Guildhall Art Gallery on Friday Oct. 16th. ?

DON:The listener will first be a viewer, wandering freely about this amazing collection, glass in hand. It’s a fine, lofty room, seating about 180, with ceremonial staircase. To reach it, you pass fine old churches and the ancient Guildhall, the beating heart of the City of London. In the gallery’s basement are traces of the Roman London of two thousand years ago. After this feast for the eyes, the concert will follow, in the gallery itself, about an hour in duration. I shall be playing a fine Bösendorfer piano.

RA:Two of the Bax premieres you’ll be performing are recitations. Can you explain what that means?

DON: Recitations are a genre that links the piano recital with its original model, the poetry recital. When Liszt started to call his concerts ‘recitals’ it was to present himself as a poet – a Tondichter, as he and his son-in-law, Richard Wagner, might have put it. In those days, a ‘recital’ meant ‘poetry’. Now, Liszt’s perversion of the phrase has usurped the original, and a ‘recital’ means music – you’d have to specify ‘poetry recital’ if that’s what you meant. In a recitation, poetry is recited while a piano plays. The one I’ve performed most often, with such actors as Gabriel Woolf and Timothy West, is Richard Strauss’s setting of Tennyson’s Enoch Arden. (I was just last month in the great Chapter House at Lincoln Cathedral, giving a song recital – that word again! – of Tennyson settings, accompanying the young choral scholars of the cathedral choir, with Tennyson’s statue just outside – he was a Lincolnshire man.)

RA: Who will be your speaker?

DON:Actors are very difficult to pin down! There might always be a film come in. Watch this space.

RA: Amanda Pitt will be the soprano soloist in the songs. What can you tell us about her?

DON: Amanda and I have given many song recitals together, including pictorial ones. Our recordings include Entertaining Miss Austen (in fact, just last night we performed songs from Jane Austen’s own music collection in her brother’s house at Chawton), the Elgar CD I mentioned, the songs of Trevor Hold, and Roger https://phenadip.com Quilter’s folksong settings.

RA: The program also includes a ballad by Elgar called “As I laye a-thynknge” from a text by Thomas Ingoldsby. What is the background of this work and how does it relate with the other pieces in the program?

DON: ‘The Ingoldsby Legends’ were very much in tune with the back-to-the-mediaeval-past ethos of the Pre-Raphaelite painters. Many writers have suggested that Elgar is THE Pre-Raphaelite composer, in works likeFroissart. I’d say Sullivan has an even greater claim to that title, while Elgar, like Millais, went on to more complicated philosophies, but certainly in his earlier works, Elgar’s music perfectly catches the brilliant colours and narrative verve of the painters. This particular song is rarely heard, because through an accident of publishing history, it was never printed during the twentieth century.

RA: You exhibit a missionary-like zeal when it comes to promoting neglected music. Where does this passion come from?

DON:‘Music is an activity by which Societies define themselves. It can be recognized by the noise it makes.’ That’s one of the definitions I polished when I was Gresham Professor of Music twenty years ago (City of London again – oldest Music Professorship in the world, founded in 1597 under the will of Sir Thomas Gresham, who coined Gresham’s Law – ‘bad money drives out good’.)

If I walk round a city I’ve not visited before, I’m as interested in the people as the buildings. If we apply that thought to Music, the ‘buildings’ are those great masterpieces that are so very familiar to us, standing there, rock-like in the estimation of the world. Fine, if a little stained by the soot of familiarity and the bird-droppings of a million performances. It’s often easier to hear the humanity in a less well-known piece, something that can surprise us and make friends with us, just like a person.

RA: You wrote the Foreword to Lewis Foreman’s third edition of his monumental biography on Bax so I think it’s fair to say Bax’s music means a lot to you. When did you first come to Bax?

DON: I was honoured when Lewis asked me to follow Felix Aprahamian in prefacing his book – a very tough act to follow. I first came to Bax through his Second Sonata, which I played at an Academy concert forty years ago – the occasion I first met Lewis, who came backstage in the interval to interrogate me on a new detail of Bax’s life I’d put in my programme note, which turned out, much to Lewis’s disgust, to be a simple error. Funny start to such an enduring friendship. I delved deep into Bax’s music at that time – friends noticed a similarity between my playing and recordings of Bax at the piano, and some of the more eccentric of them still firmly believe I’m his reincarnation! The dates don’t quite fit, in fact, and pianistic similarities are down to the great Tobias Matthay tradition that still survives at the Academy. But I found there were similarities between our musical minds – an approach to harmony, an interest in controlling form – and I happily joined in with any Bax event I could.The Blessed Damozel won’t be the first Bax premiere I’ve given by any means. When I won the Gilmore Award that took (brought?) me to America twenty-five years ago, it was Bax’s Second Sonata I played, and I’d played it, too, in the Sydney Piano Competition in 1980 that brought me a Daily Telegraph headline I still cherish: ‘Piano Contest’s dazzling loser’.

RA: You recorded the Piano Quintet for Chandos and more recently the Viola Sonata for EM Records. What do you recall about those recordings and are there other works by Bax that you’d like to record?

DON: I’m particularly proud of that Viola Sonata with Louise Williams. We’ve played together since we were both Academy students, and we both have the deepest love of the piece. When we performed it at the Viola Congress on the Isle of Man, her fellow violists were kind enough to say that we brought something different to the work, and we planned there and then to record it, though it took many years to bring the project to fruition. My liner-note analysis of the sonata is the fullest that’s been published – it’s on the EM Records website, I think. The main thing is to take Bax seriously. He knew a thing or two about diabolism – he fell under the influence of Peter Warlock, after all – so if, rather than playing what have perhaps become musical clichés, you play what the clichés mean, then you do Bax justice. You can hear the same problem in Holst’s Uranus, which is too often infected by Mickey Mouse and the Sorcerer’s Apprentice.

Other works of Bax that I’d like to record? Well, these premieres are good stuff. My recording plans for the future, however, centre for the moment upon early pianos, and then upon Constant Lambert. And there’s no point in recording just for the sake of it.

RA: Despite the advocacy of musicians such as yourself, Bax’s music continues to be neglected in the concert hall. Why do you think this is?

DON: Bax’s mind was very complicated. As with all great composers, his music is the mirror of his mind. Bax’s music is therefore very hard to understand.

RA:Which pieces by Bax do you believe represent his very best work?

DON: The Piano Quintet, the Second Piano Sonata, and the Viola Sonata. Yes, I know he’s a master of the orchestra!

RA: Are there any recordings of Bax’s music that you’re especially fond of?

DON:I often listen to David Lloyd-Jones’s Naxos symphonies.

RA: What’s the chance that a Bax work might appear in one of you BBC Radio 3 “Building a Library” programs?

DON: That’s a good idea! But my next one will be the Poulenc Flute Sonata, which I used to play with Jean-Pierre Rampal, who gave the first performance.

RA:Has Bax had any influence on your own music?

DON: He’s enriched my harmony, and echoes of his harmonic transformations of melodies can still be heard in my music. Some of my early works, now withdrawn, dabble with his formal complexity. But my music, like my broadcasting and my writing, has moved closer to the ideal of saying complex things in simple ways. Bax’s ways are rarely simple!

RA: How would you describe your music to someone who hasn’t heard a note of it before?

DON: Complex things in simple ways. Tunes, chords & rhythms.

RA: How much time do you now spend composing and what do you consider to be your most important work?

DON: Nothing like enough, and always the next one.

Seriously, my student ambition was to be a composer, but in 1970s Britain the musical establishment was unthinkingly in favour of whatever the latest aspect of a rather faded ‘modernism’ might be. Of my tunes, chords, and rhythms, only rhythms were really acceptable to my teachers, but not THOSE rhythms! I failed my Oxford B. Mus (having got a First Class in my B.A., winning a composition scholarship in the process) because in the obligatory serial piece that we had to compose in perfect silence in three hours, I obligingly appended a serial analysis, showing that, although the piece was firmly in E minor, it nonetheless obeyed all the injunctions of serial theory. At my viva I was told that this was not the point. I take great satisfaction from the fact that neither I, nor the musical public, can remember who the famous composer was who told me that. But I should be grateful to him, I suppose, since that was the impetus for my very enjoyable career as a performer. When I turned fifty, I realized that I’d done most of what I wanted to do as a pianist. I’d performed recitals and concertos all over the world, including the BBC Proms, I’d accompanied great singers and violinists: the future could just be more of the same, or I could follow new paths as well.

So, though still continuing those enjoyable activities, I turned to playing early pianos, and to composing. When you start a serious composing career at the age of fifty, you don’t have time to waste. No point people puzzling over which of my little piano pieces or songs they might try to shoehorn into a programme. So I concentrate on big pieces, of which the ones I like best are my Symphony and my Piano Concerto. I’m just orchestrating a piece that celebrates Democracy,Turning Points, based on the events of 1215 (Magna Carta), 1415 (Agincourt) & 1815 (Waterloo), which will be premiered this autumn a month before HengeMusic (see Answer No. 1). So my autumn is very full. Even more important to me than the Bax concert is the London premiere of Piano Concerto, Symphony and Turning Points, in St Paul’s Church Covent Garden, on October 1 Don’t miss it!

18. What else can we look forward to from David Owen Norris later this year and beyond?

www.davidowennorris.com will keep you up to date.

Many thanks for inviting me onto the website.s