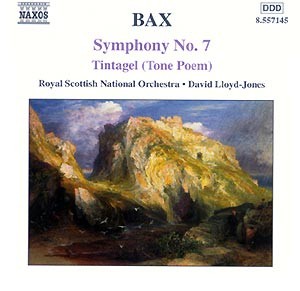

New Naxos recording of Bax’s Seventh Symphony and Tintagel reviewed by Christopher Webber

Bax: Tintagel, Symphony No.7

Royal Scottish National Orchestra

David Lloyd-Jones

THE SIR ARNOLD BAX WEB SITE

Last Modified October 14, 2003

Naxos CD: 8.557145 (56:55)

Review by Christopher Webber

Home at last. David Lloyd-Jones and the Scottish National have completed their cycle of Bax symphonies for Naxos, begun (can it really be?) in 1995. Their achievement has been to present clean, uncluttered readings in modern sound, which have induced many to dip a modest toe into Bax’s swirling symphonic waters. It’s worth emphasising that this is the first truly integral cycle – Bryden Thomson’s for Chandos was begun with one orchestra and ended with another – and bouquets are surely in order for all concerned.

The opening Allegro of Bax’s 7th, last and most mellow symphony offers a good example of the considerable strengths of the Naxos cycle. There is no hanging around, and the direct muscularity of the first few, turbulent bars is bracing stuff. As in the very best of his Naxos set, the 6th, Lloyd-Jones is secure enough in his grip of structure to allow the virtuoso Scottish woodwinds time to phrase musically without sacrificing momentum, and there’s certainly no lack of atmosphere.

What brickbats there are must be hurled at the usual suspects: thin strings, balance problems (a peripatetic harp, an inaudible flute line) and the conductor’s sometimes unsmiling efficiency. It’s not a question of his brisk tempi, but Lloyd-Jones’s literal phrasing too often runs the risk of throwing Bax’s “brazenly romantic” baby out with the bathwater. There’s too little playfulness and too little poetry, especially in the Lento middle movement, a refusal to indulge the sensuality of the moment, and many of Bax’s best musical strokes go for little. The central section of the Lento (“In Legendary Mood”) makes less musical sense here than in Thomson’s flabby but affectionate LPO reading. Only Raymond Leppard, with the same orchestra on Lyrita, really brings it off. His version remains the best in the catalogue, at least until Handley’s Chandos set emerges. Having said which Lloyd-Jones and his RSNO drive the final Theme and Variations through with gusto, and the Epilogue – Bax’s sunlit-farewell to symphonic writing – brings their cycle to a close with exquisite, poised beauty.

With one or two exceptions, notably the luxuriant Nympholept which rescued Lloyd-Jones’ disengaged traversal of the 4th Symphony, Naxos’s tone-poem fillers have done Bax scant justice. Tintagel here is no exception. It is sluggish, noisy and coarsely recorded, much more so than the slightly dry but congenial sound-picture given the Symphony. The exhilaration of the opening seascape does not last more than a few bars, as the surging, big string tune gets swamped by overenthusiastic brass. From then on the music flounders between lacklustre playing and rhythmic inertia, until the dying echo of the ill-tuned final chord brings merciful release. Although hardly the highlight of the set – the supercharged 6th is that – the main work here avoids any serious pitfalls. Graham Parlett’s lucid programme note is a bonus, and given the modest outlay this 7th Symphony offers a commendable conclusion to the Naxos cycle.

Copyright © Christopher Webber

Bax: Symphony 7;

Tintagel

Review by Roger Hecht

Appears by the kind permission of American Record Guide

The Issue (e.g. March/April 2004)

www.americanrecordguide.com

Toll Free Phone: 888-658-1907

Royal Scottish National Orchestra

Conducted by David Lloyd-Jones

Naxos 557145–57 minutes

The Seventh (1941) is Arnold Bax’s final symphony and last major work. It is a work of exuberance, reflection, and invention that is held together by Bax’s most cohesive symphonic structure. Once I accepted the common view of it as the untroubled aftermath of a struggle that raged in five of Bax’s previous symphonies before dissipating in the Epilogue of the Sixth. Now it sounds like a final battleground. I am also coming to regard the Seventh as Bax’s most accessible symphony and one of his best.

The first movement is a seascape. It begins with a roiling theme from the ocean’s depths that gives way to a heroic fanfare that rises like a sphinx from the ocean. Bax develops these two ideas, plus a stirring, limber tune in the strings, a bubbling idea for the woodwinds, and a jaunty march with a tightly constructed development that cuts back, forth, over, and beneath the waves in a kaleidoscope of colors. Effects vary from nostalgic looks backward, eerie night scenes, glowing sunlight reflecting the flutes off the horns, and bass clarinet gurglings from the ocean depths. The recapitulation begins with a wry take on the fanfare theme by the woodwinds before the brass resound it properly. A grinding climax ensues, then a troubled processional, before the movement disappears back into the depths.

The outer sections of the slow movement express Bax’s “summer languor”. ‘A’ contains a quiet swaying theme, interspersed with sharp climaxes and brooding. The trio, marked ‘In Legendary Mood’, opens with the musings of an Irish fiddler. A nightmarish waltz tune emerges and turns into a quiet processional that leads back to a more uneasy “summer languor”, where the climaxes are harsher and more drawn out. Tranquility is restored, but not without restless churning from the bassoons before the movement dissipates into the mist.

If the opening fanfare of I is heroic, the one that introduces III is triumphant. A tune of quiet dignity from the low strings begins a “theme and variations” (actually a passacaglia, since the theme changes little). At one moment it comes into conflict with a grotesque remnant of the opening fanfare, whose harsh trumpets mock the symphony’s claim of triumph. Eventually the theme reestablishes itself and moves to a sublime epilogue in the language of the prelude to Wagner’s Lohengrin.

From the ebullience of his reading, Lloyd-Jones does see the Seventh as the composer’s freedom from struggle. His performance grabs you from the opening fanfare, lifts you up, carries you along, and sets you safely on the ground, leaving you to rue Bax’s farewell, “this is as far as I can go”. Textures are bright and tipped to the upper instruments. Tempos are fast, with crisp, incisive rhythms. Generally, he leans to Bax’s impressionist side, touching occasionally on the modern in II, with an acerbic trio and some edge to the brass climaxes. The outer movements are especially good, missing neither Bax’s chimera in I nor his triumph in III, and there is plenty of vision and sweep. While he could relax more in the quieter sections of I and be more indulgent with Bax’s “summer languor” in II, he would be straying from his interpretation. The Scottish orchestra sounds thin here and there, but given the approach, this is not serious. Naxos’s wide acoustic is distant and not as detailed as usual in this series, but this is not a serious problem.

All told, Lloyd-Jones is immediately appealing, but Raymond Leppard’s more romantic Lyrita recording goes deeper. It’s more down to earth, with slower tempos, fuller textures, darker colors, and more even tonal balance. He also gives us more of II’s “summer languor”. If Lloyd-Jones’s protagonist seems young to have known such a struggle, Leppard’s hero is older and bears the scars. The greater finesse and fuller strings of the London Philharmonic help with Bax’s subtle orchestration, as does Lyrita’s richer, fuller sound and stronger bass. Each presents a vital side of Bax’s symphony. Both are required listening, and both are superior to Thomson’s too-impressionist and languid view. Now I look forward to hearing what Vernon Handley has to say in his Chandos recording.

Lloyd-Jones approaches Tintagel as a prelude to the symphony–an idea seems to support by waiting this long to give us Bax’s most popular tone poem and then placing it first on the program. After the opening grandeur of the Cornish cliffs, the vast ocean dominates, as it flows with long-limbed melody. Rubato is controlled; articulations are broad, and the bassoon rivulets pushing from below are unusually clear. The final climax is magnificent. Boult (monumental and powerful) and Barbirolli (romantic and surging) focus more on the cliffs and waters pounding below than the sea. Both probe more deeply, with Boult topping the list, but Lloyd-Jones is a solid third. All are superior to Falletta (good but lacking power and continuity) and the rather limp Thomson.

COPYRIGHT American Record Guide 2004