More Compact Disc Releases

NEW COMPACT DISC RELEASES

THE SIR ARNOLD BAX WEB SITE

Last Modified: June 20, 1999

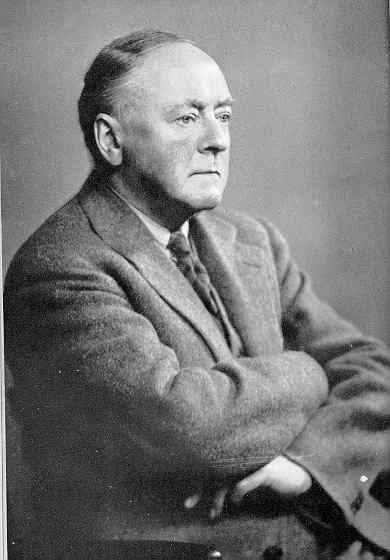

Studio Portrait of Sir Arnold Bax in 1945

NEW ISSUES

Symphony No. 2, November Woods

Royal Scottish National Orchestra conducted by David Lloyd-Jones

Naxos 8.554093

by Ian Lace

November Woods

My reason for reviewing November Woods before the Symphony will become clear later so please bear with me. Bax’s Tone Poem November Woods, written in October 1916, not only depicts the turbulence of an Autumn storm as it wracks a woodland but it also reflects the composer’s passion for Harriet Cohen. The lovers would meet clandestinely in a small pub in Amersham near the woods, covering the nearby Chiltern Hills, where Bax had once

sheltered from such a storm.

Bax’s poem Amersham sets the scene:

…..Storm, a mad painter’s brush, swept sky and land

With burning signs of beauty and despair

And once rain scourged through shrivelling wood and brake

And in our hearts tears stung and the old ache

Was more than any God would have us bear.

Then in a drowsy town the inn of dreams

Shuts out awhile October’s sky of dread

Drugged in the wood reek, under the black beams

Nestled against my arm her little head

The music of November Woods is Bax’s musical realisation of the hostile elemental forces and passionate sentiments of these verses. One of Bax’s loveliest romantic passages, sensuous, tender and passionate, is bracketed by stormy violence that is both sudden and sustained as boughs creak and branches heave under howling gales, driving rain and flashes of lightning. Lloyd-Jones’s evocation is every bit as thrilling and vivid as that of Boult (on Lyrita SRCD 231). I must say that I also admire Bryden Thomson more leisurely, but not unexciting, approach on CHAN 8307 in really opulent Chandos sound.

Symphony No. 2

Bax’s magnificent Symphony No. 2 was written between 1924 and 1926. It is the second episode in the continuing saga that is Bax’s seven symphony cycle. Its first movement catapults us straight into the violent world that was unleashed in the First Symphony (1921-22). As Lewis Foreman stated in his notes for the 1971 Myer Fredman recording of this work (Lyrita LP SRCS. 54): “The mood in this movement is that of November Woods in which an emotional crisis was depicted in terms of stormy nature, and is even more convincingly argued.” Bax described it as being “heavy with impending catastrophe.” The music is passionate and tempestuous, heavy with conflict the music tugging and grinding against itself fitfully with only brief moments of respite.

The second movement is reminiscent of Holst in his unworldy mode until Bax quickly asserts his own style with the horn call in the second and third bars. This movement is predominantly lyrical and passionate. Lewis reminded us that it had been suggested that the whole work might be viewed as “one vast love song.” Personally I think this is very much of an over-simplification but certainly the slow movement might qualify for such a description. Lloyd-Jones realises all its tenderness and passion and his climax hits you with all the force of a tidal wave. Lloyd-Jones interpretation of this symphony is a triumph – read with scorching, white-heat intensity. The ferocity of the catastrophic finale comes across with great impact. Lloyd-Jones also heeds the detail too. Note that extraordinary passage about 5 minutes into the finale where Bax creates a sound world entirely of his own a magic domain created by imaginative use of harps, tremolando strings in mid-register, percussive piano and close snare drumming in crescendo.

I would just quote again from Lewis’s notes: “The psychological interrelation of the first three symphonies of Bax has often been remarked upon, but is worth restating. The demon that possessed Bax in the First Symphony is really only presented in that work; having relieved himself of its stating, Bax expiates it in this Second Symphony, which can be regarded as a chart of his spiritual and emotional wanderings in the mid ‘twenties. Thus in the Third Symphony, written in 1928 and 1929, after the composer had discovered what was to become his artistic retreat at Morar in Scotland, he attempted a stylistic and emotional synthesis finding repose in the serene Epilogue.”

I wonder if Naxos really appreciate the value of their investment in this Lloyd-Jones Bax cycle. The release of its component parts seems slow and widely spaced in the extreme and its presentation with only a four page booklet (with no language translations) seems niggardly. And as yet there seems to be no news of the project’s completion. Keith Anderson’s notes are scholarly. He tends to have got lost in the detail of the notes rather than communicating the equally if not more essential human psychological and elemental elements of these works.

My colleague Richard Adams agrees with me that this new Lloyd-Jones album now supersedes the other existing Chandos recording with Bryden Thomson. Personally, I think it is the equal of Myer Fredman’s 1971 Lyrita recording which I hope one day we shall be able to more properly assess in a refurbished digital CD edition. As Richard has mentioned, Fredman had the huge advantage of an inspired LPO and a much better recording engineer.

Richard has also commented (and I would generally agree) “…that the sound on the Naxos Bax 2 is inferior to the sound given to Naxos Bax 1 where the strings have much more body. Bax 2 was recorded first and I suspect Naxos had not yet figured out how to record in the Glasgow Hall and Lloyd-Jones was relatively new to both the RSNO and Bax. Given all that, I think he did an admirable job and he certainly displays a strong feeling for Bax and a command of Bax’s symphonic structures.” On that last point I agree absolutely!

by Richard R. Adams

Assuming the Bax symphonies will someday receive the popular attention they so obviously deserve, I predict at least three of his seven symphonies will come to be ranked with those of Elgar and Vaughan Williams as the greatest examples of British music in that form. While Bax’s Third Symphony was for many years his most popular symphony, its reputation in recent years has suffered (rather unfairly, I think) in comparison with those of the Fifth, Sixth and Second Symphonies which are regarded by most Baxians as his most characteristic and brilliant orchestral works. Surely, one listen through of this new Naxos recording of Bax’s Second Symphony with David Lloyd-Jones conducting the Royal Scottish National Orchestra should convince any sympathetic listener of Bax’s limitless musical imagination and brilliance at writing for a large symphony orchestra.

The Second Symphony is the most deeply personal of Bax’s works, which is saying a great deal considering how much of his music is autobiographical. He poured more of himself into this work than any other. Its composition consumed him for the greater part of two years and at its completion, he said he felt physically and emotionally exhausted. Any successful performance of this work must convey the deeply troubled state of mind the composer was going through at the time of its composition. David Lloyd-Jones’ performance most certainly succeeds in this regard. From the unbelievably ominous opening with its bass drum roll and sinister motif for cor anglais, clarinet and bassoon through the middle movement’s impassioned outbursts for organ and running strings to that most desolate and inconsolable of Bax’s famous epilogues, Lloyd-Jones’ interpretation is one that emphasizes the dramatic and descriptive elements of the score. His fastidious attention to detail uncovers a wealth of instrumental color and invention. Naxos has provided a very clean but also very dry recording which allows the listener to hear much more of what is going on in the orchestra than could be heard on the Chandos recording with Bryden Thomson. I myself would have welcomed a little more ambient warmth which might have provided more richness to the string tone. The nearly 30-year old recording made by Lyrita with Myer Fredman conducting the London Philharmonic is still the preferred recording in terms of sound.

This budget Naxos recording is in almost every way preferable to the Chandos recording. Lloyd-Jones’ interpretation is as spacious as Thomson’s but he is much more successful in navigating the intricate shifts in tempo and mood and, most importantly, in keeping the music moving. So often with Thomson’s Bax the impression is given of the music being pulled out of shape in order to accommodate that conductor’s desire to wallow in Bax’s gorgeous harmonic textures. Lloyd-Jones is a much more disciplined conductor, and like that greatest of all Baxians, Vernon Handley, his aim is clearly set at giving the music shape and assuring that its structure holds together. Mention should also be made of Fredman’s Lyrita account which is currently unavailable. That fiery performance is a classic and nicely compliments this weightier and more broadly conceived performance. Its release is an absolute must but in the meantime I want to wish this new Naxos disc every success because I believe it could make many new friends for Bax and this symphony in particular. I can’t think of a more underrated masterpiece in British music.

The companion work on this disc is November Woods. The standard recording by which all new versions of this work are judged is Sir Adrian Boult’s definitive account on Lyrita with the London Philharmonic Orchestra. Both Neville Marriner and Bryden Thomson give similarly conceived performances which ultimately fail to impress as much as the Boult. Lloyd-Jones, perhaps wisely, approaches this work differently. His is the more literal interpretation of a violent autumn storm with the more introspective elements of this tone poem being underplayed. This is a brilliant, on the edge-of-your-seat performance which I suspect will be controversial but which also goes to show that great music can be played in more than one way. The playing by the Royal Scottish National Orchestra is both works is sensitive and virtuosic. I now look forward to Lloyd-Jones’ recording of the beautiful Third Symphony which is scheduled for release later this year.

Naxos 8.554093

In Memoriam, Concertante for Piano (Left Hand) and Orchestra

The Bard of the Dimbovitza, Jean Rigby (soprano); Margaret Fingerhut (piano);

BBC Philharmonic conducted by Vernon Handley

Chandos CHAN 9715 [76:40]

by Ian Lace

These are all premiere recordings and most welcome additions to the Bax discography. How splendid the orchestral version of In Memoriam sounds; Vernon Handley and the BBC Philharmonic give a really spine-tingling performance. Dating from 1916, In Memoriam commemorates Pádraig Pearse, one of the leaders of the 1916 Dublin uprising, executed soon after the rebellion was quashed. Bax was clearly greatly moved when writing this music for it conveys all the anguish he felt at learning about all the suffering in his beloved Ireland and of the veneration he felt for Pearse. Readers of Bax’s Farewell, My Youth may recall how Bax remembered meeting the martyred hero: “Scarcely had Pearse shaken hands shyly than he sat down by the fire and stared into the blaze as though absorbed in a private dream but his eyes were lit with the unwavering flame of the fanatic. Somebody said, ‘Pearse wants to die for Ireland you know.’ Indeed he did not have much longer to wait before his desire was granted. As he was leaving he said to his host, ‘I think your friend Arnold Bax may be one of us. I should like to see more of him.’…I could not forget the impression that strange death-aspiring dreamer [ Pearse] made upon me when on Easter Tuesday 1916 I read, by Windermere’s shore, of that wild, scatter-brained but burningly idealist adventure in Dublin the day before. I murmured to myself, ‘I know that Pearse is in this’…”

Bax had fallen deeply in love with all things Irish and the English censor later declared his verses, written under his pseudonym, Dermot O’Byrne, to be subversive. In Memoriam includes the theme that Bax later used for Mr Brownlow in his score for the film Oliver Twist but here it is treated with that extra passion and deeper conviction appropriate to Pearse. In Memoriam is part-elegy, part-funeral march, and partly a furious remonstration against a cruelly suppressed bid for Irish independence. (Perhaps Bax, in more reflective and prudent mood, put it aside for it was never heard and indeed, until recently it was thought that Bax had never orchestrated it). Marching rhythms with insistent side drum and bugle calls contrast with music that suggests Irish Elysian Fields fit for heroes. A wonderful musical experience.

The Concertante for Piano (Left Hand) and Orchestra was written at Storrington in 1948 for Harriet Cohen who had injured her right hand. Lewis Foreman, writing in his book, Bax, A Composer and his Times regarded this work as “watery” and “…[it] is not a successful work, and unfortunately for Bax’s reputation had the misfortune of being widely played for several years. The critical sneers it received, were by implication, extended to the rest of his music… Nevertheless, Left Hand Concertante, patently Bax’s worst extended work was widely heard. The first movement is laboured although there are some attractive ideas. The slow movement is probably the best; beautiful if limited…But the theme of the finale, a rondo, is tawdry. His heart was not in the work. He wrote to the Dutch cellist-composer Henri van Marken during its composition: ‘I find it terribly difficult to think of anything effective for the one hand…’ Except in the finale, Bax seldom brings the soloist away from the lower half of the keyboard, and so the left-hand limitation is thus rather more pronounced than it might have been. Ravel in his left-hand concerto, which Harriet never played, allowed his soloist a much wider compass…” In an interview with Colin Anderson reproduced in this CD’s booklet, Vernon Handley comments: “Margaret [Fingerhut] showed immediately that it’s not directionless – It’s very clean and clear. I admire in Bax that he doesn’t mind writing something simple. By terming it ‘Concertante’ he’s saying that the orchestral role is as important as the soloist’s…He’s written – better than Britten (Diversions) and as well as Ravel – something that uses the left-hand colour and register extremely well. The Concertante occupies a lighter emotional world but he touches moments of depth as he does in every work….”

So, the individual listener must decide. For myself, I found the slow movement to be the most appealing and in the sensitive hands of Fingerhut and Handley, often beautiful. The opening movement has many Baxian characteristics, including northern-mythological-type figures but at some points I felt these were caricatured and I could not dismiss from my mind’s eye a picture of North American Indians that the music seemed to create – maybe it was “oddities” like these that attracted such derision? The rhythmically exhilarating final Rondo is an odd mix of the sturdy and heroic with some grotesque and quirky figures plus some intriguing Brahmsian influences. Clearly Fingerhut and Handley have brought out the very best in this oddity amongst Bax’s major works.

The Bard of the Dimbovitza was composed in 1914 and it clearly shows the influence of the Russian composers, that so impressed Bax in his earlier years, as well as the French impressionists. The Bard of the Dimbovitza comprises Romanian Folk Verses collected from the peasants by Héléne Vacaresco and translated by Carmen Sylva (the nom de plume of Queen Elizabeth of Romania who was probably was more involved in their composition than she admitted) and Alma Strettel. Published in London in 1892, they became as popular as Omar Khayyam although they bore as much direct relevance to Romanian folk-poetry as Fitzgerald’s verse had to Persian verse. Bax eschews any local Romanian colour. Most of the poems in The Bard of the Dimbovitza are designated as ‘Luteplayer songs’ or ‘Spinning songs’. The influence of Rimsky-Korsakov and Sheherazade is immediately apparent in the beginning of the opening “Gypsy Song”; and there are echoes of Tchaikovsky later (‘There where on Sundays…’). It is dreamy, sultry and sensual with Bax richly evoking lines like: ‘The brook ripples by so clearly there…’ The second song, the ghostly and mysterious “The Well of Tears” again is sumptuous but chilling too as the singer sees spectres at the bottom of a well full of tears. “Misconception” appears to be about lovers’ embarrassed silences whereas simple confessions of love would have eased everything and saved the sadness that Bax later implies. This is a more fragile creation and nearer to the impressionism of Ravel and Debussy. In the more light-hearted “My Girdle I Hung on a Tree-top Tall”, with Bax’s cheeky cuckoo figures, the singer, a clearly head-strong and independent young woman scorns the attentions of a young man. Here Rigby has to sing a dialogue between swain and maid. The latter’s arrogant scorn is well represented but the former’s masculine ardour could have been more strongly communicated. The final song, “The daughter” (clearly from Bax’s treatment, a spinning song) is, again, another dialogue piece, this time between a young girl, poetic, naive and eager for love and her mother disillusioned and laconic. Rigby, in the main, sings sensitively and expressively with warmth and a fine sense of the lines of the songs and Handley provides rich, evocative support. This album is a must for all Bax enthusiasts.

LEWIS FOREMAN WRITES:

When I wrote my book on Bax I had only heard one performance of the Left Hand Concertante, that given by Douglas Fox at Oxford on a very snowy night in 1969. Later, between the two editions of my book, I encountered Harriet Cohen’s French Radio performance which, frankly, was no better. In both the orchestra could not really cope. So it was wonderful to hear it played by a top line orchestra, with Margaret Fingerhut’s crisp yet poetic performance of the solo part. For me it was a revelation.

When I suggested that its frequent performance during Bax’s last years did his reputation a disservice, I meant that by being represented by an “easy” and comparatively lightweight piece, the virile, epic, romantic Bax was forgotten. The same was true when the First, Second and Sixth Symphonies were little heard, and Bax tended to be represented by numbers Four and Seven. Lovely works, but lacking the grit of the ones that were then neglected, before even they fell out of performance altogether.

In fact, now hearing the Concertante so beautifully presented, one becomes aware of the music’s strengths. I must say I do not always care for Bax’s late music when he is using those “Indians coming down the Hudson” rhythms, as early on in the first movement. But the second subject of the first movement, particularly at its reprise, is so close to the poetic moments of the earlier epic piano concerto Winter Legends, exploring that work’s most magical vein in two wonderful passages, that we realise that Bax is not entirely divorced from his pre-war romanticism.

Then the slow movement, which on its own is revealed as a lovely encore, well able to replace the delightful “Morning Song” on any recorded music programmes. While the whole work is not on the scale, emotional or musical, of the Symphonic Variations or Winter Legends, nor is it a work on which a great reputation could solely rest, it is nevertheless a worthwhile one, and I hope it will may be taken up again from time to time.

Mentioning Winter Legends, it is interesting that this programme includes three works where Bax alludes to himself in all three; looking back to Winter Legends in the Left Hand Concertante and to Into the Twilight in the second song of The Bard of the Dimbovitza; while in In Memoriam he looks forward to the exultant climactic moment of the slow movement of the Second Symphony, in a remarkable thematic link which must set thinking all who have wondered at the tragic Second Symphony’s motivation. I find that all such resonances and allusions add to the enjoyment and understanding of this remarkable composer.

While I cannot review this record as I devised the programme and, on behalf of the Sir Arnold Bax Trust, promoted the performance and recording. But I must say that to my mind it has turned out remarkably well and illuminates so many aspects of Bax’s life and music; while each piece is one that one will surely return to again and again on this CD. A truly heartfelt “thank you” is due to the artists involved for making such a success of the scheme.

CHAN 9715

Symphony No 6 (1934), Tintagel (1920), Overture to Adventure (1937), Munich SO/Douglas Bostock. (63:08 secs)

by Robert Barnett

Of the cordillera of Bax’s Seven Symphonies, the Sixth is the undoubted peak. Including this one, there have been only three commercial recordings: Norman Del Mar’s Lyrita from 1965 which has never been transferred to CD and Bryden Thomson’s Sixth. Del Mar’s still stunning account remains unavailable and would be a strong contender despite its vintage and the oddly spot-lit recording. The Thomson on Chandos is a modern recording but is afflicted with astrange lassitude. Bax’s symphonies tempt a certain Delian meandering but benefit from a strong forward pulse even in the most lyrical moments. Bostock (a Thomson pupil) captures the spirit of fantasy and adventure so well in an account drenched in a potent blend of magic and violence. He does not allow proceedings to descend into an invertebrate dream but injects a sense of urgency and conflict and keeps things moving. He is clearly sensitive also to Bax’s love affair with beauty just out of reach and suggests this in the sense of joy lost and the peaceful but enchanted resignation of the closing pages. Tintagel is given the best performance I have heard bar only the original Eugene Goossens set of 78s from the 1920s. Bostock and his German orchestra are concentrated and passionate in projecting a sea-spattered and urgently romantic canvas. This vies only with the early Decca Boult recording and is of course a much better recording than the Decca. Lastly we have a recording premiere in the brightly swashbuckling Overture to Adventure written for Dan Godfrey’s successor at Bournemouth, Richard Austin. The orchestra is enthusiastic and accomplished lacking only the last ounce of sumptuous tone in the strings by comparison with Del Mar’s mid-sixties Philharmonia. The overture is in the spirit of many British overtures of the 1930s and 1940s having something in common with Moeran’s ENSA-commissioned Overture to a Masque. Fine recording. Good notes though anonymous. A very strong cross-section and a recommended collection featuring the key masterwork in the Bax output. Confidently recommended.

ClassicO CLASSCD 254

Fantasy Sonata; Harp Quintet; In Memoriam (1916); Sonata

for flute and harp; Valse solo harp. Marcia Dickstein (hp), Angela

Wiegand (fl), Leslie Reed (cor ang), Natalie Leggett, Rene Mandel

(vns), Evan Wilson, Simon Oswell (vas), Timothy Landauer (cello).

RCM CD: RCM 19801

by Graham Parlett

We have been treated to some really excellent CDs of Bax’s chamber works over the last couple of years, notably the two complementary collections on Hyperion (CDA66807) and Chandos (CHAN 9602). Now comes a new disc containing wonderfully full-blooded performances of Bax’s harp music from the Los Angeles-based label RCM. (This has nothing to do with the Royal College of Music, by the way; the initials stand for ‘Rubedo Canis Musica’, which the company translates as ‘Red Dog Music’, though what Bax – not to mention my old Latin teacher – would have said to that I’m not sure.) The programme begins with the world première recording of a short Valse that the composer wrote for Sidonie Goossens in 1931 as a ‘thank you’ after she had given the second performance of his Fantasy Sonata. This is a curious jeu d’esprit-Bax’s only work for unaccompanied harp-with a ‘key’ signature unique in his output, namely an F sharp and a B flat, indicating a combination of the Lydian and Mixolydian modes centred on C. It receives a vigorous performance from Marcia Dickstein, who has also edited and published the score (Fatrock Ink, through Theodore Presser in the USA and Universal Edition in the UK). After waiting eighty-one years for a first recording, In Memoriam (1916) for cor anglais, harp and string quartet (1917) can now boast two performances on CD. The Chandos recording is slower and in places more reflective than the new one, which brings out the passionate feelings that underlie the score, its ‘inspiration’ deriving from the terrible events in Ireland during 1916. Both interpretations are very good indeed, though the RCM first violinist sustains her final high notes more securely than in the rival recording. There have been no fewer than nine recordings of the Fantasy Sonata for viola and harp (1927): two on 78s (both with Maria Korchinska, the dedicatee), two on LP, one on cassette only, and four on CD (including one, on the Koch label, still to be issued); there is also a version with the harp part played on the piano (Olympia). Some performances of this work have been rather lacklustre, but this new one stands among the very best. The viola tone is strong and rich and Evan Wilson plays with great feeling and authority. Perhaps the opening could have been taken slightly faster-the marking is Allegro molto-but thereafter the tempi are very well chosen and the players are able to integrate a structure that, in lesser hands, can sound rambling and episodical. The dance-like second movement in particular goes with a real swing, while Dickstein and Wilson play the closing pages of the work with ecstatic fervour. The Harp Quintet (1919) has not fared nearly as well on disc. Neither the Chandos nor the Hyperion version really does the work justice, and my favourite recording has hitherto been the old 1950s one played by Laura Newell with the Stuyvesant Quartet on a mono LP (long out of print and never reissued) on the American Philharmonia label. However, I think this new version is even finer. Bax’s initial tempo indication, Tempo Moderato, tends to inhibit performers, and it is refreshing to find Ms. Dickstein and her colleagues playing the opening with a greater sense of forward movement than usual. There is great fire and passion in the faster sections and delicacy in the quieter passages. An altogether heart-warming version of this beautiful work. To end the programme, Marcia Dickstein and Angela Wiegand give a marvellous performance of the Sonata for flute and harp (1928), which Bax later arranged as a Concerto for septet (to be found on the recent Chandos chamber music disc). This again was only recorded for the first time a few years ago but has now notched up three versions. The Beynon sisters’ performance on Metier (MSV CD92006) is first-rate, better played, I feel, than the French version on the Arion label, which also includes several wrong notes thanks to the inaccurate printed score that the performers used. In the outer movements both the Beynons and Dickstein/Wiegand give sparkling performances, but in the beautiful slow movement the newcomers reveal a wider variety of moods than their rivals, especially the music’s unexpected sinister side. Incidentally, the title of this piece is given on the CD as ‘Sonatina’, which is how it appears on the manuscript. However, it was first performed as ‘Sonata’, and this seems to have been Bax’s preferred title and the one under which it has been previously recorded. Before making her own recording, Marcia Dickstein made a thorough study of a photocopy of the manuscript and found a huge number of errors in the score published in the USA. Her own definitive edition is published, like the Valse, by Fatrock Ink. The quality of the recording is excellent (‘true 20-bit digital’), and the attractively produced booklet is enlivened by Ms Dickstein’s enthusiastic notes. However, the Arnold Bax Society to which she refers to several times hasn’t existed for twenty-five years: I think she must mean the Sir Arnold Bax Trust. And in case anyone who has read the notes gets hot under the collar at the implication that Lewis Foreman and I have been despatching original manuscripts across the Atlantic, I should point out that it was photocopies of the Sonata and Valse that were provided, not the holograph scores themselves. Marcia Dickstein, who devised the programme and plays superbly throughout, is to be warmly thanked for all the hard work that she must have put into getting this CD made. I hope that it may now be possible for her to record Bax’s remaining harp works: Elegiac Trio, Threnody and Scherzo, Concerto for seven instruments, the Vivaldi Concerto arrangement for harp and string quartet, and perhaps even Of a Rose I Sing, a Song for chorus, harp, cello and double bass, and the Variations on the Name Gabriel Fauré for harp and string orchestra. Strongly recommended.

(c) Graham Parlett

RCM CD: RCM 19801

ARNOLD BAX (and others) – CASSETTE REVIEW

BAX: Piano Sonata in E flat (1921)

SCRIABIN: Fantasy Op 28 (1900)

FRANCK: Prélude, Chorale and Fugue (1884)

Noemy Belinkaya (piano) Max Sound Bnai Brith cassette ONLY MSCB104

by Rob Barnett

I was pleased to discover the existence and survival (it was issued in 1989) in the catalogue of the Jewish Musical Heritage Trust. The Jewish connection here is in the soloist who is a Latvian living in Israel. The works were recorded during 1989 in the ample though not over-plush acoustic of London’s Wigmore Hall.

The sonata dates from 1921 and was the famous (well at least among Bax fans) work which signalled that Bax had in fact written a symphony. His friends Arthur Alexander and Harriet Cohen persuaded him to produce a symphony from it. This became Symphony No 1 (recently issued on a Naxos CD) although the central movement of the piano sonata was discarded and a completely new one written. Here we have the original piano sonata with the two outer movements we are familiar with from the symphony. The sonata receives a glimmeringly powerful performance at a high voltage. The Russian temperament comes across very well in a work obviously influenced by Bax’s romantic adventure in Tsarist Russia in 1910. The language much affected by Balakirev, Glazunov and Scriabin is similar to the tumultuous bell-like music of the numbered first piano sonata. This performance was also available on an Ensemble cassette (again no CD) ENS136. The Ensemble cassette had the advantage of more Bax as a coupling though the unbelievably off-key title of ‘Bax Bonanza’. For the record the other items on the cassette were Fantasy Sonata for viola and harp and the Polish Christmas Carol Fantasies. There is some pre-echo on the Maxsound tape but no more than expected and only apparent at very high listening volumes. There used to be a CD of this sonata (Continuum CCD1045) but I believe that Continuum are now no longer available. In any event the performance by John McCabe was uncharacteristically low voltage or at least lower than the flood unleashed by Belinkaya.

The Scriabin and Franck works receive romantically free-wheeling performances though the Franck tends toward the turgid. Whether this is the work or the performance I cannot say. The recording is fine but with the inescapable though very discreet tape hiss. The cassette is certainly worth seeking out by any Bax enthusiast. A no-compromise performance of a commanding Bax score.

© Robert Barnett

The cassette (there is no CD) can be ordered from the Trust for £7.99

plus £1 Post and Packing in UK and £2 outside UK. Phone 0181 909 2445

Fax 0181 909 1030. E-mail enquiries to [email protected]

Octet (horn, piano, string sextet) (1934), String Quintet (1933), Concerto for flute, oboe, harp and string quartet (1936), Threnody and Scherzo for bassoon, harp and string sextet (1936), In Memoriam for cor anglais, harp and string quartet (1917) – (All Recording Premieres)- Margaret Fingerhut (piano); Academy of St Martin-in-the-Fields Chamber Ensemble. (71:43 secs)

by Robert Barnett

Here, in a lovingly recorded and generous anthology, is the answer to Baxians’ entreaties and prayers. In one lacuna-filling disc Chandos have given us five recording premieres. All of these are works which are rare even on radio … never mind in concert! With the Chandos CDs of the Piano Quintet (an epic symphony for a chamber group and not to be missed!); String Quartet No. 1 and the Nash Ensemble’s excellent Hyperion collection of more ‘mainstream’ chamber Bax, this CD fills out yet more of the landscape of Bax’s music. It also means that ageing radio tapes can be relegated to the back of the cupboard.

Recording quality is rich and deep without being too plush. All strands come over clearly and make a telling effect. The performances are lovingly shaped by the Academy of St Martin-in-the-Fields (ASMF).

The core around which other soloists come and go throughout these works is a string quartet lead by veteran Kenneth Sillito. The harpist is Skaila Kanga who was also the soloist on the very early Chandos LP (and then CD) which coupled String Quartet No. 1, the Piano Quartet and the Harp Quintet. In the Octet the ASMF are joined by Margaret Fingerhut whose artistry has already given us the Bax Saga Fragment, Winter Legends and the Symphonic Variations, all on Chandos. Perhaps her Irish and Ukrainian ancestry account for her obvious empathy for the music.

None of the five works is all that long. The longest, at about 20 minutes, is the Concerto; the shortest is In Memoriam (1916). All but this last work date from Bax’s vintage Northern years: the 1930s. Echoes of the symphonies of that era can be heard but in a format which is perhaps less intimidating. Certainly these works avoid the clichéed criticism of dense glutinous textures. Speeds are brisk but there is plenty of repose and that essential willingness to dream momentarily. There is much tough magic and glimmering beauty in these scores and it is well caught in these performances.

The Octet opens as if a horn concerto with plenty of exposure for this super-romantic instrument. The performance has a nice sense of poise, playfulness and heroism. Fingerhut makes her contribution as one of the ensemble though commandingly presented here and once or twice Winter Legends-like rippling figurations call to mind that symphony manqué. Highly attractive and certainly high-water-mark Bax.

The String Quintet (1933) is an intense work and is well presented here. Interesting to hear at least one echo of RVW’s ‘Snows at Christmas’ from On Wenlock Edge. It is not a work I will want to return to that often but I am glad it is there for discovery and reappraisal.

The Concerto (1936) is the longest work here with three movements of varying emotional landscape and incident. The first is bright and flowing. The second offers an evocation of a Curlew-like wasteland without quite the intensity of bleakness and devastation of Warlock’s cycle though still powerful and attention-holding. The third movement offers bright and arresting music. The richer variegated palate offered by these forces is well used and we should be grateful that Bax transcribed it from its original format as a sonata for flute and harp. The ensemble matches that of Ravel’s Introduction and Allegro and ensembles should seriously consider this piece as an unhackneyed companion to Ravel’s delicate world.

Among the rarest works here is the Threnody and Scherzo. The Threnody harks back to the Third Symphony in its main theme. There is a tranced otherworldliness about the piece which is not without bubbling wit which is in much in evidence in the Scherzo.

With In Memoriam we come back to Bax’s Irish soul. The sense of concentration is at its highest here and Bax was clearly gripped when he was writing the piece. The power of this recalling of happy days and heroes lost still has the power to shake. The textures are almost orchestral and the spectre of The Firebird stands over a number of incidents in what Bax called his Irish Elegy. It stands as one of Bax’s strongest works.

The CD is topped off by notes by Lewis Foreman. These are, as usual, informative and well written. The booklet is in Chandos’ usual trilingual format. Booklet design is excellent. Too easy to overlook the acknowledgements on p. 22 of the booklet which note the help and support of the Bax Trust and Nicholas Briggs who appears to have played an important part in bringing this disc into existence. Thanks then go to Chandos, the Trust and to Mr Briggs. The disc is warmly recommended. © Robert Barnett

Chandos CD CHAN 9602

In the Faery Hills; The Garden of Fand; Symphony No. 1. Royal Scottish National Orchestra conducted by David Lloyd-Jones. CD only. 64:05. Naxos 8.553525 DDD stereo. Bargain

by Robert Barnett

Here at last is the first issue in this Naxos project which, when completed, will give the first ever Bax symphony cycle with one conductor and one orchestra. Lyrita used various orchestras and conductors and Chandos regrettably switched away from the Ulster Orchestra after recording Symphony No. 4 and some tone poems with them. Something went out of the veins of that project when that happened. Rumours of a Handley Bax symphony cycle (on EMI Eminence) to match his RVW cycle never came to anything. Although I have not given up hope yet, our best chance of hearing Handley in Bax symphonies may well be the reissue of radio tapes from the early 1970s though even then he did not broadcast all them (only 3, 5, 6 and 7).

The warmest of welcomes then to this Naxos project. This is the first issue in a series which will encompass all the Bax symphonies and major tone poems. The series is planned to be complete by the end of 2000. Symphonies 2, 3 and 5 are already, I believe, in the can along with a selection of tone poems. The ‘cordillera’ of the Bax symphonies has many and varied summits. No. 2 is a peak but so also are numbers 5 (dedicated to Sibelius) and pre-eminently No. 6 (dedicated originally and revealingly to Szymanowski but finally switched to Sir Adrian Boult). Personally I hope that Naxos will extend the series to include Spring Fire and Winter Legends and it might even be worthwhile to look at some of the even earlier orchestral efforts.

I first came to hear any of Bax’s music while a business studies student in the very early 1970s. This was while I was living in Torquay in Devon miles away from the main cultural centres. At that stage I relied on radio broadcasts and LPs borrowed from the library. Buying a Bax LP was out of the question: all of the Lyrita orchestral series were at full price.

Naxos are to be thanked in the most practical way by buying their recordings. They have made available a wealth of rare, worthwhile and often masterful and enjoyable music at bargain and super-bargain price. Naxos are also remarkable because their CDs are also sold in places other than specialist CD outlets. Large racks of Naxos CDs can be found in Woolworths and other venues. They have played a role in democratising music; surely significant at a time when my (rather distant) impression is that the average age of concert audiences is increasing. Let’s start hearing Bax’s music being used in commercials and getting some more exposure! His music has been used as background to adaptations of children’s TV and radio serials (Tintagel in ‘Treasure Island’) and I recall November Woods being used in the ‘Onedin Line’.

Well, enough of the polemics and the nostalgia! What about this recording? The Royal Scottish National Orchestra is a full-size orchestra needing very little, if any, augmentation. Its approach to repertoire is liberal (note its successful forays into film music). Alexander Gibson and Neeme Järvi established its Northern and international credentials. Now they have ventured into Bax a composer whose soul-allegiances were assuredly both Northern and Western, Atlantic and Gaelic. Bax’s regard for Sibelius and his music (which was also reciprocated) is well-known. The RSNO are no strangers to Sibelius having recorded the symphonies and tone poems under Gibson. Gibson’s Classics for Pleasure/EMI LP of Sibelius Pelléas and Mélisande was and remains a classic. It will be interesting to hear the accents and approach of the orchestra in the more centrally Northern works such as Symphonies 5 and 6 and Tale the Pine Trees Knew.

The pieces on this CD all have an Irish accent and subject matter. Personally I would not get too wound up in the stories and plots behind the two tone poems. I have always found literary plots distracting. The emotional ‘plot’ of the music is all you need. However it is good that in Keith Anderson’s notes all of the plot details are there if you really want them. But I repeat that tussling with which part of each section of music represents a particular episode is a pretty destructive and arid exercise.

The pieces are all comparatively early, with the symphony being the latest. In any event the music dates from well before Bax (or listeners) had any grounds for thinking that his inspiration had burnt low or flickered out. In these years Bax’s compositional confidence was high and musical invention flowed strongly.

The insert booklet has very full notes. The main section of the notes are also in French and German omitting artist profiles and some of the background on the Bax piece. Booklet design is simple but effective. Irish green predominates. Everything is legible and no sign of the arty effects so beloved of those often given free rein for these things – we can all think of examples. I fail to see why imagination in design of such things is often at the expense of utilitarian qualities such as legibility. The eldritch green-toned painting ‘Twilight’ by William J Webbe (can anyone tell me more about him?) is in character with the preternatural elements of the music.

The recording is strong on clarity and depth. If anything the recording favours the exuberant brass and it does so to very great effect. I say this despite the very modest and rather ancient nature of my hifi setup.

The sessions were in the Henry Wood Hall, Glasgow on 31 January 1996. The engineer and producer is Tim Handley (a relative of Vernon Handley?)

I wonder if some of the excitement with which this series has been deservedly greeted is the sense of joy that there is to be a sequel to the Chandos Bryden Thomson series. I bought each of those Chandos CDs as they were issued but with few exceptions I found that they presented the music less than ideally. Bryden Thomson’s Symphony No. 4 with the Ulster Orchestra was, and remains, wonderful as also does his Winter Legends and one or two other items. However much of the series was afflicted with a somnolent approach to the driving forces in Bax’s music. My impression is that the many beauties of the music tempted Thomson into slower tempi and not enough variation. This was accentuated by the plush and resplendent Chandos recording textures. There are static, almost Delian, moments in Bax but they must be allowed to stand as part of an overall forward-moving, driven approach. This is something which Vernon Handley has commented on before in interview with Ian Lace. David Lloyd-Jones, a conductor with the strongest British music credentials, is clearly sensitive to the need to keep the music moving forward. His approach is responsive and plastic with the ability to adjust the pulse of the music so that the many incomparable poetic moments are allowed to grip the listener. He also has a fine feeling for accenting of phrases and balancing of the complex scheme of dynamics. Bax’s preoccupation with yearning for the unattainable comes over very strongly and there is a crippled sunset splendour about the wilder moments, particularly in the symphony.

Symphony No. 1 is dark-hued and barbaric. It strikes me as being one of a kind, not just among the symphonies but also among all his works. Recently I have been reading ‘The Cauldron of Annwn’ (the trilogy of poetic plays by Lord Howard de Walden set as a cycle of music-dramas by Joseph Holbrooke) and much of the strange atmosphere and preoccupations of that cycle seem to fit with Bax’s first symphony. It is dedicated to John Ireland but it is Holst and especially the Holst of Egdon Heath that is often recalled. This is especially true in the darkness of the second movement (lento solenne). The Symphony receives here a performance to match. This is quite a short symphony running just over 32 minutes in this performance. The performance (last on the disc; Tracks 3-5; 13:41, 10:21, 8:26) is passionate and completely eclipses the Chandos/Thomson version. The Lyrita CD which couples Myer Fredman’s performance of Symphony No. 1 and Leppard’s of No. 7 remains a strong contender though inevitably out-pointed on recording quality. Fredman’s performance is imaginative and the orchestra share his vision and commitment completely. The Symphony No. 7 is a substantial and generous coupling but the Lyrita is at full price. Overall, though, on recording quality, interpretative qualities and on the basis of a well-balanced coupling the Naxos is at the head of the field. What of the tone poems? Fand has been recorded by Beecham, Thomson, Boult, Barbirolli and Slatkin (ed. as part of a Chicago Symphony Centennial Set ). It is an evanescent piece the charms of which are moth-wing fragile. For me the Beecham still has the edge. The Beecham, by the way, is the recording which was used in Ken Russell’s sensational film of an (imagined) episode in Bax’s later life when he takes an exotic dancer to the Cornish scene of his earlier romantic idyll with Harriet Cohen. She is shown dancing in the sunlight beside the waves while Bax plays the 78s on a wind-up gramophone. The Lloyd-Jones version (Track 2 16:32) has its magic but does not give the wildest rein to fantasy in the way which Beecham does. The Barbirolli version is also very highly rated. These perfectionist observations must not detract from the virtues of the Naxos version. The more I listen to it the more am I drawn to it and the recording is so impressive and analytical that one keeps discovering new details in the score. If you were to discover Fand via this recording you would be hearing a very fine performance. I wonder what the same team will make of Tintagel? I am still waiting to hear a version of that piece which rivals the first recording on 78s which was conducted by Goossens. A small cavil: the opening of Symphony No. 1 follows without sufficient pause after the closing bars of Fand. The silence should have been allowed to continue for longer.

In the Faery Hills has been a favourite of mine ever since I first heard it in an early morning broadcast by the BBC Concert Orchestra conducted by that unsung hero of British music, Ashley Lawrence. Please do not be put off by the twee title. Try to think of it as being a natural step onwards from Balakirev’s Tamara, Rimsky-Korsakov’s Sadko and Scheherazade (echoes of the latter in the Bax Violin Concerto) or Rachmaninov’s Isle of the Dead. In fact the liberating Russian element is also strong in the other two works. This performance (Track 1 15:04) has all the fantasy and dreamlike beauty you could ask for. The pellucid quality of the recording displays Bax’s interweaving musical strands to great advantage. The horns and brass appear rich and forward. At 6:39 the viola, underpinned by a harp ostinato, sings the theme with great tenderness and this is taken up by cor anglais, bassoon, and then French horn, each with the harp figure making a consistent pulse. The hopeless despair and inhuman epic quality of the music is brilliantly caught by everyone at 8:40.

HNH International Ltd through Naxos/Marco Polo are to be congratulated for their ambitious recording plans. These have been very publicly announced. I am sure that there was some initial scepticism. Issues such as this go a long way towards dispelling doubts. In fact they fuel the highest hopes that Naxos will go from strength to strength and that not only will we see, by the end of 2000 the complete Naxos series of the orchestral works of Vaughan Williams, Bax, Parry, Stanford and Moeran but also orchestral works by Frank Bridge, Arthur Butterworth, John Veale and Derek Bourgeois among others. I should add that these latter names represent only my wishful thinking.

I look forward with keen anticipation to the second release which may well contain two of my favourite Bax pieces: Symphony No. 2, November Woods (his strongest tone poem which also bids fair to be his best work of all) and, if I am very lucky, the often derided Sibelian tone poem The Tale the Pine Trees Knew (actually I believe this may be reserved as a coupling for Symphony No. 5). The Symphony is a work of wonderful drama – a great love poem with an epic grandeur borne high on tunes out of Bax’s top drawer. I am sure Ian Lace is spot-on in tracing its molten invention to the love affair with Harriet Cohen.

Anyway, enough about the next instalment. If you have never heard Bax before, then buy this CD. You will rapidly become an addict. This is also for those who were none too sure about Bax or British music generally and would like to explore. This is music by a British composer which is an antidote to pastoralism. If you have enjoyed the Russian or French romantics you will want to try this. It will open doors for you into a world of wild imagination and, that rare commodity, beauty. Bax addicts will already have bought the CD and will be enjoying it now. These same people will be clearing a space on the shelves in readiness for the next six volumes. Meantime warmest thanks to Klaus Heymann (a British Music Society member) of HNH. We need visionaries like him. Long may this venture continue and please record the other Bax symphonies as soon as possible.

Naxos 8.553525

The Piano Music of Arnold Bax – Volume 4

by Ian Lace

The Slave Girl/Legend/What the Minstrel Told Us/Whirligig Toccata/In the Night/A Mountain Mood/Mediterranean/Serpent Dance Ceremonial Dance/Dream in Exile/Paean/Salzburg Sonata Movement

Some seven years separate Vols 3 and 4 in this entrancing series for it was in 1990 that Chandos released the previous volume of Bax Piano Music. This time 13 pieces are included but it is definitely not an unlucky collection in the sense of quality and enchantment. The usual Bax heady romance is here and there is a dreamy feel to many items especially those associated with Harriet Cohen such as What the Minstrel Told Us, Dream in Exile and A Mountain Mood which is hardly rugged but very feminine and lyrical. Even more romantic is In the Night, here receiving its premiere recording. It is dated 1914 but was never performed or published in Bax’s lifetime. Some non-musical imagery can be inferred from Bax’s poem of the same title telling of a cathartic walk with a girl friend, starting “Along the quiet streets I walked with her, While pale enormous stars froze in the sky.” Could the girl friend have been Harriet I wonder? She was certainly established in his circle of friends by then. Anyway the music seems to suggest some very private feelings and of lovers transported and lost in a little world of their own. A more exotic and sensual number The Slave Girlis definitely associated with Harriet for Bax wrote it for her at the high point of their romance. Two of the pieces are associated with Bax’s ballet The Truth About the Russian Dancers – i.e. Serpent Dance which is quite Russian sounding and is a sly dig at typical ballet steps; and Ceremonial Dance which is a slightly truncated piano reduction of the overture to the play The Truth About the Russian Dancers while the second idea comes from Bax’s earlier unperformed ballet Tamara. Whirligig, premiered too, is a brilliant and cheerful bit of whimsy; and the other premiered piece, the Salzburg Sonata (Lento espressivo) movement is a clever pastiche of Mozart. Eric Parkin, as usual, penetrates to the heart and spirit of these works, his interpretations are unhurried yet agile, carefully considered and articulate. I should add that my colleague Richard Adams who administers the Bax web site feels that Parkin needs to drive the assertive Paean a little harder.

by Richard Adams

I’ve been waiting for this disc a long time. This is Volume 4 in the Chandos Bax piano music series with Eric Parkin. The first two volumes in this series were released nearly a decade ago and they contained the four sonatas as well as some smaller works. Volume 3 was released in 1990 and it was made up entirely of smaller (in size — not necessarily in scope) miniatures. While Volume 3 was a very full program, it nevertheless left out several gems. I’m delighted to see that many of those magnificent miniatures have turned up on this disc and I’m even more happy to report the performances by Eric Parkin are perfectly judged in almost all instances. In fact, my only complaint is with the rather subdued approach Parkin takes with Paean – – a wonderful study in ostinato in Lewis Foreman’s words – – which should sound a little more driven than it does here. Otherwise, the tempos are ideal and Parkin’s performances are intensely expressive without ever becoming too sweet. Anyone who has ever attempted to play these works will know the pianist is faced with layer upon layer of ornamental detail that must not be allowed to overwhelm the primary melodic line. Parkin succeeds with playing that is utterly clear and translucent. His agile finger work in such pieces as Whirligig, Toccata and the very Debussyian The Slave Girl is marvelous to hear as is the delicacy of his playing in some of the more ravishingly beautiful pieces such as What the Minstrel Told Us, Dream in Exile, A Mountain Mood and Serpent Dance. I believe this disc along with the other in the series gives ample proof that Bax was perhaps the greatest British composer of keyboard music in the first half of this century. This disc is an absolute must for Bax fans as well as those who love late romantic and impressionistic piano music.

CHAN 9561 – Eric Parkin, pianist