John McCabe and Robert Barnett discuss Arnold Bax

Last Modified January 5, 2000

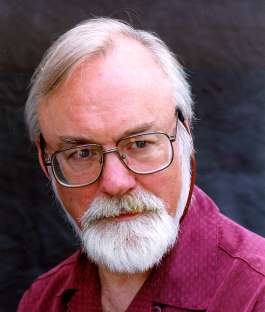

John McCabe is one of the most distinguished British composers of the latter half of the 20th Century. He is also a magnificent pianist whose repertoire extends from Haydn to John Corigliano. He is president of the British Music Socitey and a devout champion of the music of Arnold Bax. What follows is an interview with John McCabe by Robert Barnett, editor of the British Music Society Newsletter. I want to think Rob for allowing me to post the interview on this site.

by Robert Barnett

Robert Barnett: When did you first encounter Bax’s music?

John McCabe: I can’t remember when – I know that I heard some on the radio as a child, and I saved up my pocket money and bought the 78s of Barbirolli conducting the 3rd Symphony when I was still only about 7 or 8. So I was hooked quite early! I really have no idea what drew me to Bax’s music in the first place. I suppose the Celtic blood in me responded to the magical aura of Bax’s music, the sense of seeing beyond. The slow movement of the 3rd Symphony, for me, has always been music of sheer paradise – a depiction of the Celtic paradise, Tir Nan Og, perhaps.

RB: Do you recall any outstanding Bax concert performances which captivated or influenced you?

JM: Unfortunately, even in those days there weren’t all that many live performances of Bax that were easily accessible. I grew up just around the corner from the Philharmonic Hall in Liverpool, and we did get the 3rd Symphony a few times there, and it made a great impact on me, as I’ve already suggested. Apart from that, and the occasional tone poem performance (usually Tintagel or Fand), there wasn’t a lot. There were more symphony performances in Manchester, but in those days I didn’t get to those. In the Halle’s centenary season, which was my first year as a student in Manchester and was a really great festival of memorable performances, there was the Violin Concerto, which I loved, and since then I heard Barbirolli and others do a few things – JB did Tintagel and Fand superbly, of course, and Maurice Handford later made an attempt to get Bax back in the repertoire with splendid performances of the 3rd and 4th symphonies. I simply don’t understand why conductors don’t fall over each other to do some of them – they compare very favourably (more than favourably) with pieces they do seem to like, such as Scriabin symphonies and so on. Incidentally, some years ago in Australia I bought a cassette of a superb recording of No 3 by Myer Fredman and the Sydney Symphony Orchestra which was of the highest quality – it refreshed my enthusiasm for Bax at a time when I was concentrating on other things, so it served a very useful purpose.

RB: I have always been impressed (too weak a word) by Symphony No. 6. Do you know it? What is your impression and what are your views on the strengths and weaknesses of the other symphonies?

JM: No 6 is to my mind one of the very finest. The only relatively weak ones seem to me No 4, which is very enjoyable but has for me something of the air of being written to a formula, and No 7, though I do think it is underestimated – the only problem really is that the material is perhaps stretched out too thinly, because I suppose he no longer had all the intellectual or emotional energy for works of that scope, but it does contain some marvelous music. Nos 1 and 2 are superb, but I often think the finales have a tendency towards bombast – having said that, I must admit I am a sucker for such total commitment. I also feel that the orchestration, of which he was usually one of the great masters, tends on the odd occasion to a thickness which prevents one from hearing the harmonies clearly enough. I don’t think this happens with the symphonies from 3 onwards, but I think my view is supported by the piano sonata original version of No 1, where you can compare the harmonic clarity of the piano version with the orchestral textures in the outer movements. I had the great delight of recording the piano version, and I felt that it proved my point – not that there are many places where this criticism of the orchestral sound applies, just a few odd corners.

RB: You are one of the few pianists who to my knowledge has played Bax’s Winter Legends. What drew you to the piece?

JM: I’d read about Winter Legends, of course, but I got to know it when I was asked to play it with Ray Leppard and the BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra, as it then was, in 1977. I believe it was the BBC themselves who suggested it to me. If you’re going to play a piece like this, you’ve got to like Bax’s very personal style from the outset – otherwise, it will be most uncomfortable. Fortunately, I was already a devoted fan, and right from the start I knew that this was one of the high spots of his output. Again, as with the symphonies, I simply don’t understand the neglect of this great work, and I should perhaps say that it’s absolutely marvelous to play. Technically it isn’t particularly difficult, except for getting the opening of the finale absolutely even and quiet (which is nerve-racking), but it uses a terrific range of dynamics and pianistic colours. I found it very practical for me because it never (or hardly ever) demands a stretch wider than my small hands can cope with – but I believe Harriet Cohen had small hands, and it was written for her.

RB: Were the performing materials in a good state or did they require to be redone or reconstructed?

JM: The orchestral materials were, as far as I can remember, in manuscript! The Manchester players were really quite upset about this, since they naturally need to mark up the parts with bowings and so on, and they were very conscious that by doing so they might be damaging some historic materials. I was very impressed by their sensitivity to this. One thing, which also applied to my other broadcast of the piece, was that we had to make cuts compared to my solo part: two, one in each of the second and third movements. It was because of the orchestral materials, and actually I think the second one at least is a wise one, since at that point the finale is stalled a bit – very beautifully, though. Possibly they were the result of revision. When Margaret Fingerhut recorded the piece for Chandos later on, she was able to do it complete.

RB: What are the challenges of Winter Legends technically and interpretatively?

JM: Apart from the occasional big chord, of which there are only a few and they can legitimately be spread, the only technical problem is the opening of the finale. Interpretatively I think there are two challenges. The first is that you have to get a balance right between playing with soloistic bravura and authority and playing in a more concertante manner – it is not, after all, a concerto pure and simple, though the solo part is a very big one (less rests than in most concertos, actually). There are lots of places where you have to be aware of the handing-over of your material to the orchestra, and vice versa. The other problem is simply playing with enough weight when there is a big orchestral bit followed by a big piano solo – the piano mustn’t sound weedy in comparison, so you really have to go for it (which I enjoyed). Actually, the balance in the second performance, in Glasgow, was really not right – I think the producer (I can’t remember who it was) thought “Ah, this is a concertante piano part” and balanced it accordingly, so that at one point even a solo xylophone is in danger of drowning the piano. The balancing is done by the pianist and the conductor – a normal concerto balance is preferable, because it’s much easier to play down than to play up, beyond a certain point.

RB: Are there any parts of Winter Legends which you particularly enjoyed hearing and/or performing – if so which?

JM: There aren’t any bits which stick out as more memorable than the rest. It’s all inspired music. But I think I’d have to say that the beginning of the Epilogue strikes me as especially beautiful, and the piano writing throughout is full of lovely touches (the acciaccaturas decorating the second movement’s main theme, for instance).

RB: Have you perhaps performed Winter Legends with student or amateur orchestras?

JM: I’ve never performed it with student or amateur orchestras, but I think it would be splendid to do so if the players were up to it – Bax does make considerable demands on certain instruments (horns, for instance), so they need to be good. But it’s a thought worth pursuing. I don’t know anyone else who has thought of playing it apart from Margaret Fingerhut, who did that excellent performance for Chandos.

RB: Have you looked at or considered any of the following for performance: Saga Fragment; Symphonic Variations; Left-Hand Concertante?

JM: The Saga Fragment I recorded for Chandos in its version as a Piano Quartet, and liked it very much, though I think it has problems in both versions. A lot of it is real chamber music, and despite the clever orchestration with trumpet, percussion and strings, I think some of it is roughed over in the orchestral version. By the same token, the Quartet becomes too strenuous and orchestral towards the end to be satisfactory on single strings – I know the players really got very tired each time they played it. So far as the other works are concerned, I really wanted to record the Left-Hand Concertante (I would love to have recorded Winter Legends, of course!) – it looks to me very charming and delightful, not top-drawer Bax perhaps but still well worth doing. The Symphonic Variations has always seemed to me too much of a good thing – I ll probably offend people who think it’s his greatest work, but I can never get a sense of where the work’s centre or fulcrum is, and I need to know that.

RB: One of my favourite Bax works in any genre is the magnificent Piano Quintet. Any views? Do you know it? Have you given any performances of it?

JM: The Piano Quintet is superb, I agree. I haven’t played it – I looked at it once, but this is a case where the writing demands a bigger hand than mine, or that’s the impression I got. (The same is true of the Bridge, which is another marvelous piece I can’t contemplate!) I was delighted when David Owen Norris did such a super recording, which filled one of the major gaps in the recorded Bax repertoire – and, indeed, the Piano Quintet recorded repertoire, too. I haven’t tackled the Piano Trio, either, which I like very much.

RB: Winter Legends was first played by Harriet Cohen. Did you ever hear her play it or discuss the piece with her?

JM: I never heard Harriet Cohen play, nor did I meet her, unfortunately. I’ve always wondered about the wisdom of forbidding others to play a work (Winter Legends was reserved solely for her), especially since I ‘ve been told, whether rightly or wrongly, that she didn’t actually play it very well. It can’t have been the small hands, since the work is very cunningly written, as I’ve said – possibly she didn’t have enough of a big tone to match the orchestra. I’ve developed a much bigger tone over the years, or at least the capability of producing a bigger tone – the thing which really made a difference was playing the John Corigliano Concerto in the mid- 80s, when I simply had to do so or give up, and I don’t like giving up.

RB: Did you compare impressions with other pianists at any time? I believe Patrick Piggott may have looked at Winter Legends but was allegedly prevented by HC. Did you ever discuss the work with him?

JM: No, I didn’t discuss the work with other pianists – I told one or two people I was doing the piece and they seemed nonplussed, rather than interested. If it isn’t called Concerto, of course, then they’re not bothered – the Walton Sinfonia Concertante, which I think is a terrific piece, suffers from the same attitude.

RB: You performed the piece twice. The first was with Raymond Leppard conducting the BBCNSO (now the BBCPO) and then 3 years later with Vernon Handley and the BBC Scottish SO.

JM: It was interesting to be able to compare the two performances I did, with Leppard and Handley – I liked both of them very much (I’ve worked a lot with Tod Handley, of course, and think he’s a truly great conductor). They both adore Bax – I very much enjoyed Ray Leppard’s recordings of the 5th and 7th, as well as a BBC broadcast he did of the 3rd which was very fine. And I can never understand (there are a lot of things I don’t understand!) why Handley hasn’t been asked to record all the symphonies – he’s the obvious person to do it. Curiously enough, though there are clear differences in approach at times, they both responded very directly to the power and colour of the music, and both of them understand the importance of the lower registers in the symphonic working-out, which not everybody does. People think the tune is always on the top, which is not always the case with Bax.

RB: Did you get any letters or other feedback after your first broadcast of Winter Legends?

JM: A few people wrote with nice comments, and from time to time they have recalled the Bax performances while discussing something else with me.

RB: How did your second performance come about? Was it your idea or Handleys?

JM: The second performance was, I believe, Tod Handley’s idea.

RB: Did you discuss Bax’s music with Leppard?

JM: Leppard and I chatted a bit about Bax, and I know that he’s done a certain amount in the States – I noticed he was doing Tintagel in Chicago one time, which must have been quite something, with that orchestra! So far as I know he’s never done Winter Legends again, certainly not with me and when I knew him he wasn’t at Indianapolis. In any case, it would be extremely difficult to get a rare British work of this kind into an American symphony series – there are too many pressures on the repertoire (if they get a soloist it must be in a standard work, and if not then it must be an American performer, and so on). I was most impressed that he was able to persuade a record company into doing the Sinfonia Antartica with his Indianapolis orchestra, but VW is much more like a repertoire composer over there. Nor have I done it again, with Tod Handley, though we’ve talked about it from time to time and I’m sure it will happen one of these days. He and I have had some splendid conversations about British music in general, though since we’re both enthusiasts the mention of one name in passing starts off another conversation, so we tend to flit from one composer to another. We both agree Bax is a very big composer, a major figure, who, in most other countries, would not be so shamefully underestimated, and I think we both feel that, far from being a wombling, rambling and rather slip-shod craftsman, he was actually a very serious and convincing symphonist with a magnificent sense of the ebb and flow of structure. I personally feel that some of the least satisfactory Bax is in the little romantic piano pieces and the like, where the ideas are really rather second-hand, though still strikingly Baxian on many occasions.

RB: What did the orchestras make of Winter Legends?

JM: Orchestras tend not to be very communicative about the music they’re playing until they really know it well, and you need a few performances before that stage is reached, particularly with as complex a writer as Bax. I think both the Manchester and Glasgow orchestras enjoyed the piece, and one or two people said (which will not surprise you) that they wished they played more Bax.

RB: Were there any interesting markings on the score from which you worked which was presumably the one from which Harriet worked?

JM: I worked from the piano solo part (not even a 2-piano reduction), though I did have sight of a full score for a short while during the preparation. No markings at all, though as I’ve said we did discover that there were two passages in my part not in the material being used.

RB: Did you ever meet Bax?

JM: No, I never saw him, unfortunately. There is the story that at the time when he died, in Ireland, Harriet Cohen is reputed to have felt his presence in her kitchen, which is a supernatural story roughly on a par with the wonderful black cat which appeared on the platform and sat there during Constant Lambert’s Memorial Concert and then stalked off at the end – Lambert was a great cat lover.

RB: How do you rate Winter Legends amongst Bax’s own output amongst the work of British composers among music of the 1920s and 1930s generally?

JM: Winter Legends seems to me fully up there with most of the symphonies – perhaps 3, 5 and 6 are a shade tighter in organization, but it is a wonderfully powerful piece, certainly one of his great ones. Among British piano concertos (and I persist in thinking of it, ultimately, as a concerto) I think it has a very high place, though there are just a few which I think are even finer, by a short head. It’s difficult to assess its position in music of the 20s and 30s generally, because we’re assessing it now with the benefit of hindsight. Bax still remains very much an undiscovered country.

RB: Do you have any particular recommendations amongst the chamber or solo music?

JM: The sonatas seem to me a mixed bunch. I love No 2, which I’ve played and recorded and is one of the greatest British sonatas, and No 4. which is more clear cut but still absolutely characteristic (and it has a wonderfully delicate Celtic slow movement). No 1 I think possibly goes over the top a bit, and No. 3, which has some wonderful ideas, I don’t find so memorable – It starts off splendidly but I don’t personally think it sustains the inspiration. The E flat Sonata, the original version of the 1st Symphony, is for me The Great Romantic Sonata from this country, a staggering piece – the slow movement is, of course, completely different from the one in the orchestral version, and a beautiful, sweeping sea-scape. It’s odd that he did actually write the orchestral one for piano originally and then replaced it with a different piece, before he got down to writing the symphony – a wise move, because the piano version of the orchestral slow movement is quite unplayable and doesn’t work at all whereas it’s very fine on the orchestra. I was a bit off-hand about some of the solo pieces a moment ago, so I ought to say that there are some very good ones. The Legend (unpublished) is highly effective, and I’ve always had a liking for things like In a Vodka Shop and A Hill-Tune. It’s the sort of Pre-Raphaelite pieces with which I have a problem. We haven’t mentioned the Violin Sonatas, but this seems to me a very significant area. Erich Gruenberg and I recorded the first two, which are exciting and powerful pieces, and there was a plan to complete the set by doing a disc with No 3 (which in some ways is the best) plus the original violin-sonata version of the Nonet, which works beautifully, and some other unpublished stuff. It’s a pity the second disc never happened, because it would have been very interesting – somebody ought to publish the Nonet in this version, because it’s as fine as any of the published sonatas (as you might expect).

RB: What views have you encountered from record companies, the BBC, producers and orchestral managements?

JM: I haven’t really discussed Bax much with orchestral managements and so on. The problem is that there is so much music to discuss, and one often senses not so much a disparagement of Bax as a psychological aversion to the style – and I must say it has a strong character which might not be to everyone’s taste. Delius is similar, though of course he benefited from a supreme interpreter in Beecham who pushed his music like mad throughout his career and really put him on the map. Bax never really had a single committed interpreter to single him out in this way, though Barbirolli did a lot for him. But JB’s repertoire was enormous, and he was in any case even more deeply committed to VW.

RB: I recall an English piano music LP in which you performed the middle movement of Bax piano sonata 4 alongside other British pieces. How did this recording come about?

JM: The LP called Pastorale which I did for Decca in the 1970s was done because there was a piano and a recording set-up available for a spare day in between sessions someone else was doing, and I took the opportunity to set down some repertoire I wanted to record. I did the Bax because it seemed to fit the programme perfectly – one shouldn’t really take a single movement out of context, but it was one of his favourite pieces of his own, and I felt it was absolutely perfect for the context. It was also an opportunity to draw attention to Bax ‘s piano music in a programme which I hope would bring it to people who were unaware of this area of his repertoire. In any case, someone told me the other day that Liszt used to play the slow movement of the Hammerklavier Sonata as a separate piece! (Which would work rather well.)

RB: I have greatly enjoyed the Continuum CD. How did this project materialize?

JM: The Continuum CD materialized as a result of discussions between Murray Khouri, who runs the company, Lewis Foreman, and myself – they got the manuscript of the Sonata in E flat sent to me and I was knocked out by it, so we programmed it with the 2nd Sonata and the Legend, which was suggested by Lewis, I believe. I’ve played the E flat Sonata in the USA and Australia since then, and had a terrific response to it.

RB: I d be interested in hearing your views on Moeran whose music has some kinship with Bax’s.

JM: Moeran is a composer who seems to get better and more interesting the more you know his music. As with Bax’s 3rd, I bought the 78s of his G minor Symphony when I was a child and was bowled over by it. If I were a conductor I’d be trying to programme it all the time! I felt for a long time that this was really head and shoulders above his other music, but I’ve come to appreciate the subtlety and depth of his work over the years – helped, it must be said, by the performances Barbirolli used to give of the Violin Concerto. Once you get past the reminiscences of Delius and Sibelius and so on, you realize that actually this is no more disturbing than the influence of Mahler or Purcell on Britten, and is absorbed into a very personal language. I recorded the F sharp Rhapsody for piano and orchestra, and hope it will be reissued one day, because it was a treat, a splendid piece – once again, not a Concerto, though, so people can’t be bothered!

RB: To what extent if any do you think that Bax’s music has influenced your own?

JM: I don’t think Bax has particularly influenced me in any way, except for one deliberate gesture: in my brass piece Cloudcatcher Fells, I deliberately paid homage to both VW and Bax in the central slow movement, which is very connected with my lifelong love of a particular place in the Lake District and the music of both of them. Curiously enough, nobody seems to have spotted the fact that the tune is Baxian which I would have thought was obvious.

RB: Do you perceive the influence of Bax’s music in the music of other composers? I have always thought that the music of William Mathias carried some Bax hallmarks – I can recall being quite struck by this in his Elegy for a Prince.

JM: I can see what you mean about Mathias, though I don’t know Elegy for a Prince – but the slow movement of the Harp Concerto has a Celtic brooding which is very compatible with the Baxian world. I’m not aware that many people know that Rawsthorne loved Bax’s music at one time, though he rather lost interest in it later on. One very fine composer who I think has been influenced by Bax is Alun Hoddinott, though it’s again the darkness, the purple and dark blue colouring of the nocturnal music rather than any specific aspect of style that seems to me to show a kinship (better word than “influence”).