Graham Parlett and Christopher Webber review the new Naxos recording of Bax’s Winter Legends on CD

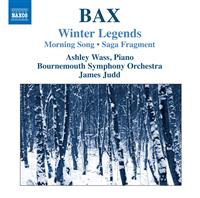

Bax: Winter Legends; Morning Song (Maytime in Sussex); Saga Fragment.

Ashley Wass (piano), Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, James Judd.

Naxos 8.572597 [56:13]

Recorded in The Lighthouse, Poole, Dorset, 21-22 June 2010.

Review by Graham Parlett

Bax’s new Winter Legends (Harriet Cohen) longwinded rambling boring stuff — so feeble and dull after the Ireland [Mai-Dun]. (From Benjamin Britten’s diary.)

Well, the teenager was entitled to his opinion, but many admirers of Bax’s music take a different view, and the composer himself ranked it among his best works. However, it is clear from newspaper reviews of the time that Winter Legends left many contemporary critics disappointed:

. . . as a whole [it] hardly seems to rank with the finest things of Bax’s recent symphonic work. It is diffuse and laboured, though the labour is relieved by so many exquisite moments of sound. (The Times, 11 February 1932, p. 10.)

It brought less to an admirer of Bax than he had hoped to get from it. Perhaps no other work by Bax is a more profuse display of his peculiar luxuriance. Where it failed was in the ordering of the luxury. In the course of the three Symphonies it had been plentifully hinted that Bax was working towards a more disciplined way of expanding and connecting his thoughts. In the present work he has relapsed, and the music explains itself bit by bit, each bit better, if possible, than the last, but defeating the ear’s longing for growth and continuity of effect. (Musical Times, March 1932, p. 264.)

To-day we have in ‘Winter Legends’ a remorseless study in the present-day mood of analytical psychics. Nothing is full and fair and in the round, it is all contingent. It was conceived perhaps in the spirit of the age, but is already out of date: this age is burgeoning in hope. (The Observer, 14 February 1932, p. 12.)

I have no idea what The Observer’s music critic is trying to say, but the following passage from Harriet Cohen’s autobiography, A Bundle of Time (pp. 201-2), suggests that the newspaper should have sent along a photographer instead ― the result would have been far more interesting:

At the rehearsal there was an expression of really touching solidarity among the senior composers for, apart from some young ones dotted about the hall, I noticed from the platform that Arnold, sitting in the stalls, was flanked on either side by Gustav Holst and Vaughan Williams.

What a fascinating picture that would have made. I wonder whether Bax’s two distinguished colleagues formed a more favourable impression of the work than the young Britten.

Whatever one’s view of the score ― and I know one keen Baxian who feels that there is too much stopping and starting in it ― I am sure that this excellent recording will win it many new friends. It is clear right from the start that this is going to be a vigorous and totally committed performance. The opening low orchestral chord, which sometimes fails to register, is quite audible here, and the ensuing piano ‘whirlwind’ (Bax’s word) is played with tremendous energy. The fast passages in this first movement are generally taken at a quicker pace than in any other performance that I have heard, with largamente markings taken less broadly than usual. This is characteristic of the performers’ urgent view of the work and has the effect of making it sound as if we are listening to a live, concert performance. The final section (marked ‘Trionfale’) has plenty of swagger, though I wish there had not been an unmarked reduction in the wind dynamics of the second bar in an attempt to let the strings’ triplets come through; but everything is back on track at the next bar, and it is impossible not to be swept along in the glittering grandeur of Bax’s closing pages, with the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra on top form. The concluding cadence sounds more decisive here than in any other performance I have heard.

The second movement is all that one could wish for, with the soloist making the most of the extreme contrasts in dynamics and mood. Highlights include the exquisitely soft playing of the brass, the ferocious eruption of sound from the orchestra’s nether regions, the overwhelming climaxes later on, and some sensitive playing from the solo violin. Following Harriet Cohen’s 1954 performance (available on Dutton CDBP 9751), Wass and Judd cut nine bars in this movement, unlike Margaret Fingerhut with Bryden Thomson and the LPO (currently on Chandos CHAN 10209), who play the work complete. The cuts are indicated in Bax’s full-score manuscript and were either made by him or with his approval.

Again, there is little to fault and a great deal to admire in the finale, which begins quietly with a solo tuba against rippling arpeggios on the piano and sustained strings chords. Both pianist and conductor manage the many changes of mood and tempo with great aplomb, and the final climax, just before the epilogue, is overwhelming. As in the second movement, a cut is made in the epilogue (again following Harriet Cohen’s performance), and here I think it is a decided improvement, the deleted passage striking me as being an unnecessary intrusion. But if you want to hear the movement complete, there is always Margaret Fingerhut’s recording, which is also extremely well played, though less clearly recorded. We knew from their CD of Bax’s Symphonic Variations and Left-Hand Concertante (Naxos 8.570774) that Wass and Judd make a formidable team, and this new recording of Winter Legends can only enhance their reputation. I gather that they have never performed together in a concert, something that ought surely to be rectified as soon as possible.

Morning Song, the second piece on this disc, has always struck me as being a perfect work of its kind: an amiable, unpretentious, tuneful piece of light music tailor-made for its purpose: the twenty-first birthday of the present Queen, who, following the death of Sidonie Goossens aged 105 in 2004, is the only dedicatee of a Bax work still living and one of the dwindling number of people who actually knew him. Harriet Cohen’s recording with Malcolm Sargent, originally on a Columbia 78 rpm disc and now on a Symposium CD (1336), is most successful in capturing its easy-going mood, which, as Bax described it, ‘derives a good deal from the Sussex spring time. It is quite a simple and lyrical work with nothing dramatic in its development’. The new recording (7:11) takes the allegretto tempo marking somewhat faster than in Margaret Fingerhut’s Chandos performance (8:09), which was itself faster than Harriet Cohen’s old Columbia recording (8:31), but I soon found myself adjusting to the speed. Ashley Wass plays the solo part beautifully and, where necessary, with rhythmic precision, and the Bournemouth players sound as if they are relaxing and enjoying themselves after the rigours of Winter Legends. The performance has an irresistible joie de vivre and the various solo contributions from the woodwind and the leader of the orchestra are most sensitively played.

A complete contrast in mood is provided by the third work on this disc, Saga Fragment for piano, strings, trumpet and percussion. Shortly before the recording began, James Judd decided to reduce the number of string players in this piece to make it more in keeping with its chamber-music origin: it was originally written in 1922 as the Piano Quartet. This wirier sound is quite noticeable when compared with Winter Legends and Morning Song, especially when the strings are playing fortissimo, and Wass and Judd bring to the work an even darker quality than in the powerful performance on Chandos by Margaret Fingerhut and Bryden Thomson with the LPO. According to Harriet Cohen, the piano-quartet version was admired by Bartók, and one can see why: nothing could be further removed from the notion of Bax as a dreamer in the Celtic twilight. But it must be extremely difficult to play in that form, though a music critic was sufficiently impressed to call it ‘a fragment of genius’ after the first performance. The orchestral version was made in 1932, and Bax described it as a ‘tough pill’. The work opens vigorously with repeated chords before the piano enters with the principal theme, played here with tremendous attack. The opening pages are exhilarating, and contrast is provided by the soft intertwining solo strings, again played most sensitively, as is the following andante con moto, which leads to a catchy, rhythmic tune with a hint of the blues in it. The ‘development’ section contains several pages of beguiling sounds with the soloist playing mysterious scales to accompany the thematic material in the trumpet and strings. The last few pages of ‘March Tempo’ are taken at a cracking pace, and it is a tribute to the skill of the trumpeter that he manages to play his final flourish so well at such a speed. I am not sure that Bax intended the ending to be played quite so fast, but it certainly brings the work (and the CD) to an exhilarating conclusion. If you like your Saga Fragment lean, mean and reckless, then this new recording is for you. If you prefer something a little less impetuous but by no means lacking in vigour and rhythmic precision, Margaret Fingerhut’s Chandos recording (using a full body of strings rather than a pared down one) is an excellent alternative, despite the cavernous recording. What we still lack, though, is a really first-rate performance of the original Piano Quartet score, neither the Chandos version (CHAN 8391) nor the Meridian (CDE84519) being entirely satisfactory.

The sound quality on this new Naxos disc is very good, with a powerful bass, enabling the listener to appreciate, for instance, Bax’s idiosyncratic use of bass clarinet and double bassoon. At a first hearing it seemed over-resonant, but my ears soon adjusted and I heard many orchestral details in Winter Legends that had never come through so clearly in previous performances, such as the passage for four solo violins in the slow movement, which usually sounds feeble but here comes across as Bax must have intended. Just occasionally some of the woodwind detail fails to register, but the scoring is very thick in places and there is simply not enough time at recording sessions to deal with every single last detail of balance. The booklet notes by Andrew Burn are informative, and there is an appropriately wintry scene on the front cover. A shame, though, that the name of the excellent trumpet soloist in Saga Fragment is not given anywhere in the documentation. For the record, he is the BSO’s principal trumpeter, Peter Turnball.

© Graham Parlett 2011

Review by Christopher Webber

I’ll come clean. Most lovers of Bax have a blind spot, and mine is the massive concertante work Winter Legends. Its brazen savagery and monochrome intensity have attracted many admirers down the years, not least the composer himself who wrote, in a letter to Adrian Boult after the premiere, that “I am not sure that it is not one of my best things.” The double negative is telling: what are we to make of a substantial three-movement work (with epilogue) which is not quite a symphony, not quite a concerto and not quite a gigantic tone poem? Thirty years after first hearing Winter Legends, and despite my admiration for its many moments of arresting imagination, I still have difficulty getting my bearings. It does not stick. There again, not warming to its elusive, chill bleakness might be the point.

Bax wrote or orchestrated much of the work in 1929-30 at his winter retreat, Morar on the West Coast of Scotland. Morar looks two ways – out across white sands to the western isles of the Celtic sea, inland to the hard northern crags of the Grampians; and Winter Legends was perhaps the first of Bax’s major orchestral utterances to look to those Northern wilds rather than the milder seascapes of the West for inspiration. It marks a change in musical style, too, from the generous abundance of the 3rd Symphony to a tight, wry harmonic language and brittle sound palette, featuring a battery of percussion effects including an icy xylophone and baleful, shivering gong.

Winter Legends has appeared twice before on CD. Most of us, I imagine, cut our teeth on Margaret Fingerhut’s uncut 1986 edition with the LPO under Bryden Thomson, which with its slow tempi and resonant acoustic certainly conveys the gargantuan mood, if losing out in forward momentum and orchestral clarity. Even in its most recent incarnation (Orchestral Works, Vol.7) the Chandos recording is strident and lacking in body, far from their best. This was valuably supplemented in 2005 by an off-air mastering (from Dutton) of Harriet Cohen’s 1954 broadcast with the BBC SO under Clarence Raybauld. Despite sonic limitations and imprecisions of ensemble, the dedicatee’s performance better conveys Bax’s wayward, romantic sweep and obsessive hard-edged forward impulsion.

The new Naxos issue squares the circle nicely, combining the amplitude of the Chandos disc with the urgent fantasy of Cohen’s reading. Ashley Wass surpasses her in virtuosic security, and his pinpoint accuracy can convey weird things, mechanistically cold and strange: listen to his way with the oddly “bluesy”, ambulatory main theme of the slow movement or the haunted “poisoned fountain” arpeggios at the start of the third to hear what I mean.

James Judd, to his credit, is prepared to risk exceeding normal Bax speed limits. His performance is nearly five minutes (!) shorter than Thomson’s, partly due to the decision to take Bax’s optional cuts in the second and third movements; but Judd’s allegros harness a fierce thrust and dynamism which makes sure we’re not mired in detail. It’s not the Bournemouth orchestra’s fault if some of the ear-shattering climaxes sound congested, and I’m not inclined to blame the Naxos engineers either. Are there perhaps moments in this score where the composer miscalculates just how loudly, and for how long, his full orchestral forces can batter away at us? Yet Bax comes up with some wild effects, such as a jaunty, Petrushka-like dance in the first movement for syncopated piano, bass tuba and tambourine, and the sardonic, bare-bones xylophone against striding timpani later in the same movement, which are pure magic. Such things come across most vividly here, and if you’re new to Winter Legends the Naxos is without a shadow of doubt the disc to have.

If Naxos’s concertante balance in Winter Legends is convincing, it’s equally so in the two shorter works, more than makeweights in this splendid addition to the Bax discography. If Wass’s cool pianism offers less melting charm than Harriet Cohen’s own reading of Morning Song, he captures the music’s lightness and fresh innocence with sure hands. And for me the best comes last with Saga Fragment, Bax’s own orchestration of his 1922 Piano Quartet, a terse and punchy evocation of those Northern Wastes and “battles of long ago” which the composer described as “rather a tough pill”. Its memorable themes and compressed textures said as much to me in ten minutes as the main meat managed in forty; and Judd, Wass and the (reduced) Bournemouth forces deliver Saga Fragment like a series of fierce hammer-blows to the solar plexus. Wicked.

© Christopher Webber 2011