Following Bax to Ukraine

Written by: Alan Sutton

Arnold Bax spent at least two months on the Skarzhinska Estate at Kruglik, near Lubny in Ukraine between May and July 1910. Alan Sutton recently visited Lubny and Kruglik and found some interesting historical background to the Skarzhinska family and to pre-revolutionary Lubny, impressions of which Bax took back with him and incorporated into later works.

“Fair and smiling is the Ukrainian land, a fecund Slavonic Demeter”, wrote Bax at the opening of this section in “Farewell, My Youth”. Ukraine was known as the breadbasket of Russia during the last years of the Tsars, and to that extent compares well in modern times with agriculture being the one sector to have prospered in recent years. In other respects, the 20th century has not been kind to Lubny, and the Skarzhinska Estate itself has disappeared: nor was I able to find precisely where it stood. However my visit did uncover some fascinating history about Natalia Skarzhinska’s family, and other pictures and impressions which will be of interest to those interested in Arnold Bax and his works.

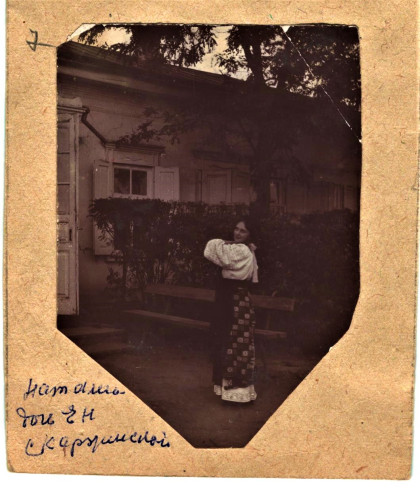

Natalia Skarzhinska: taken in 1912

In “Farewell, My Youth,” Bax relates how he had decided, on impulse, to accompany Natalia Skarzhinska, with whom he admits to having been besotted, and her companion Olga Antonietti, to Ukraine, travelling by train first from Lausanne – to which Natalia and her mother and brother had been exiled – to St Petersburg, and then on to Ukraine. Natalia he renames Loubya Korolenko, and Olga is “Fiammetta”. He arrived at St Petersburg on Orthodox Easter Eve of 1910, and stayed there for approximately two weeks before travelling on to Lubny via Moscow. One remark to make at this stage is that of chronology, and it is remarkable that Bax did not comment on this when recording his impressions of crossing the border from Germany into Russia. That is that the dates which he gives in “Farewell, My Youth” while he is in Russia and Ukraine are Julian calendar dates. Russia did not adopt the Gregorian calendar until 1918, and Orthodox Easter in 1910 was, under our calendar, the first of May. However, under the Julian calendar, it was 18th April, and so when Bax is talking about his stay in St Petersburg “that April”, his dates are local ones, and his description of the heat in May in Ukraine, given that the temperature usually rises steeply at the end of the month makes more sense once local dates are applied. It is just odd that his impressions of the differences on crossing the border into Russia do not include going back in time 13 days.

The Sharzhinska Family

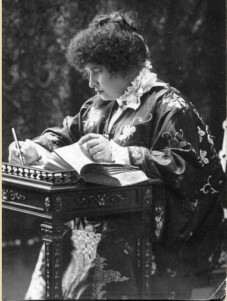

Katerina Skarzhinska

Bax is not very fair with Katerina Skarzhinska, Natalia’s mother, whom he calls “Madame Korolenko” and records as “a woman of violently Pan-Slavist opinions”. Katerina was in fact a noted philanthropist and founder of the first private ethnographical museum in Ukraine. She has her own page on the Ukrainian and Russian language versions of Wikipedia and she is the subject of various studies by local historians in the Poltava region. Her work was continued by her older daughter, Olga, Bax’s hostess at Kruglik, and the two maybe warrant a diversion from the topic of Bax’s visit as they give the background to what seems to have appeared to have been to Natalia as a stultifying provincial lifestyle from which she sought to escape. Needless to say, their history also made tracking down Natalia much easier.

Katerina Skarzhinska (née Reiser) was born in 1852 into an aristocratic family of Swedish-Pomeranian origins, who gave her extensive home education before sending her, at a time when women did not attend University, to the Bestuzhevsky school in St Petersburg. This was one of the first institutions in Russia designed for the education of women. Here she became acquainted with the Hermitage collections and prominent historians. Meanwhile in 1869 she married the future cavalry general Nicolai Skarzhinsky, a landowner, horse breeder and senior figure in the Poltava government and the marriage was seen as uniting two local aristocratic families. On returning to Kruglik, she financed archaeological excavations and built up a collection of over 20,000 historical and numismatic artefacts which in 1885 became the first private historical-ethnographical museum in Ukraine. It became particularly noted for a massive collection of painted eggs (or “pissanki” in Ukrainian) traditionally produced at Easter under Ukrainian folk traditions and forever mistranslated by everyone as “Easter eggs” which they are not. Entry to the museum was free. Katerina was also prominent in the movement to develop education for the lower classes and girls. In 1880 she donated land from her estate at the village of Terni, about 3 miles on the opposite side of Lubny from Kruglik, on which was built the lower agricultural school (today the college of forestry) and a school, library and reading room for the children of peasants at Kruglik (today School № 9, Lubny). The subjects taught make interesting reading – Holy Law, Church Slavonic, Russian calligraphy, grammar and reading, Choral singing. This was the school at which Bax’s host Lvov Klimov (wrongly remembered by Bax as as Lvof Kiriloff) taught. Only later, primarily it would appear under the instigation of Olga, were more practical classes such as carpentry, smithery and teaching in the Ukrainian language introduced.

- Agricultural college

- Student hostel at agricultural college

- Plaque at Kruglik school

- School at Kruglik

College, hostel and school: the legacy of Katerina Skarzhinska

Katerina’s relations with Nicolai Skarzhinsky may have had something of convenience about them. Bax refers to him as having lost a lot of his land as a result of accident, but exploring the history of his wife would suggest that much of it was given away in different causes. Tatyana Safronova of the Lubny District Museum informed me that the couple lived apart in the two separate houses which appear in “Farewell, My Youth”. Nicolai lived in the old wooden building where was Bax’s apartment, and Katerina lived in the modern building. In 1891 she engaged Sergiy Kulzhinsky as curator of her museum, and while the first three of her six children, including Olga and Natasha, were fathered by Nicolai, the remaining three were fathered by Kulzhinsky. So while the sources I consulted by modern Ukrainian historians may like to elevate Katerina to a position of sanctity, and point to the continuation of this in her daughter Olga, one can perhaps see something of the characters of both Olga and Natalia in Katerina.

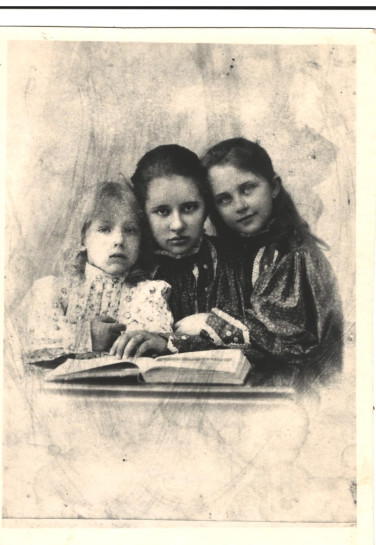

From right to left: Natalia, Olga Skarzhinska and Igor Skarzhinskiy, taken approximately 1905. The eyes and characters of the two sisters seem more evident in this picture than in the later ones

In 1906, when Katerina and Natasha were exiled, the museum was donated to the City of Poltava, which still possesses the collection, Lubny having rejected it on the grounds of expense, and, as Bax has noted, Katerina and Natasha embarked on a period outside the country arriving eventually in Lausanne. A further reason for the move may have been that Katerina wanted her illegitimate son by Kulzhinsky, Igor Skarzhinskiy to be educated and attend University in Lausanne, as Kulzhinsky later joined them there. In Lausanne, as Bax notes, Katerina “became editress of a Russian quarterly founded for the promulgation of her political creed”. This was a publication called “Za rubezhom”, something of a pun in Russian as while the phrase would normally be translated as “abroad”, literally it means “beyond the borders” This was a publication favouring the movements which spawned the Revolution and there appears to have been correspondence between Katerina and Lenin, who was also in exile in Switzerland at that time. In any event, following Katerina’s return to Ukraine in 1916 and the Revolution, rather than – as might be more usually the case – being among the first to be liquidated by the revolutionaries, she was granted a small pension by Lenin.

During her absence from Kruglik, Katerina entrusted her Estate and charitable work to her oldest daughter, Olga Skarzhinska-Klimov and it would appear to have been continued diligently by the two, although not without a certain amount of chaos. Bax remarks on Olga first being “gentle and docile”, but later as “tender-hearted but woolly-minded” and he comments on her adoption of various deformed peasant children who were running around the place. However, despite the pension and philanthropy, the Estate and lands were confiscated by the authorities following the Revolution, and following the death of Lenin in 1926, the pension too was cancelled by Petrovsk. In fact it was Kulzhinsky who would appear to have been the more saintly, as he took on the task of supporting Katerina and much of her family till her death in 1932, the year of Stalin’s famine. Tatyana from the Lubny museum took me to see the house at Gogol St, number 10, where Katerina died in poverty. It is a depressing red brick single storey cottage such as can be seen on nearly any street in Ukraine, and she did not have the cottage to herself, just one room in it, sharing the building with about 10 others, who may or may not have been other Kulzhinsky family members. a very sad end for such a worthy person.

As to Natasha, she appears to have stayed mainly in Lubny. The “brute” she married was Karl Frantsevich Selezhinskogo, a theatrical producer. Whether or not he was a brute was not clear, but the museum sent me a copy of a flyer for performances in Lubny in which both Karl and Natasha took part – in 1920 under the auspices of the local Soviet of Deputies – as well as a letter dated 1966 from their daughter Nata, remembering productions where they had acted together. Natasha, as we know, survived the famine of 1932-1933, but only just.

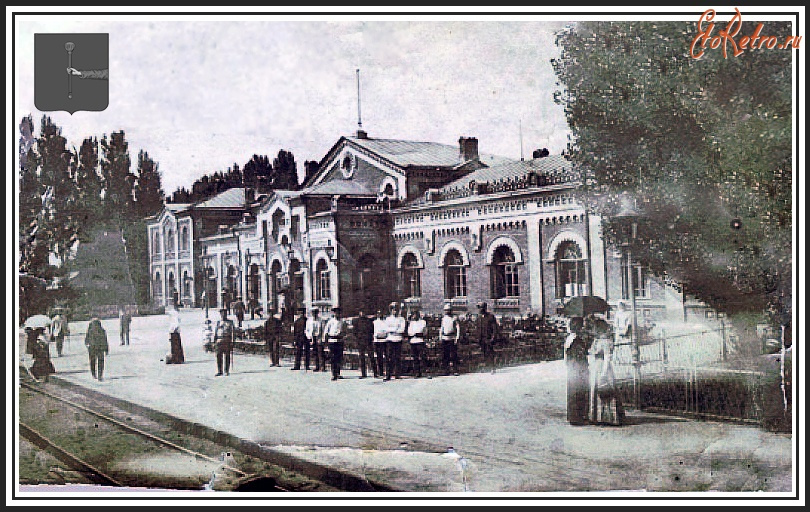

Lubny Station, then and now.

Terni

Bax arrived in Lubny by train from Kiev, a journey then of 7 hours. The traditional sleeper compartment-type train now takes three to three and a half hours to do the same journey and the express sit-up train to Kharkov can do it in two and a half. Anyone wanting the luggage rack experience should buy a third class (platzkart) ticket. In my case, I arrived in Lubny from the opposite direction after being jolted for seven hours on a minibus. I visited Terni first that evening. This is a walk of about an hour down a long dusty road in exactly the opposite direction of Kruglik. This takes one past Gogol St, some houses of the same single storey brick design, and an arboretum belonging to the college of forestry. On the other side of the road from the college are some student hostel buildings also dating from the same period. Finally, a walk of about 10 minutes from the college, is a street named after Katerina Skarzhinska. It is an unmetalled track of about two hundred yards’ length such as the road on which I live, and I was told that there was no reason why this particular street was named after her, other than that the authorities had decided to name a street after her and this one did not have a suitable name.

Lubny and Kruglik

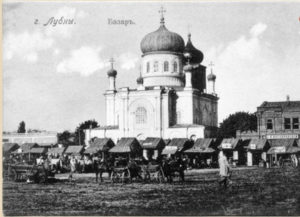

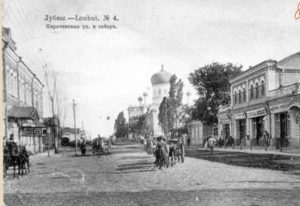

- Market

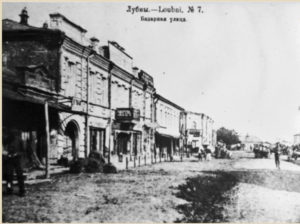

- Bazaarnaya ulitsa

- Piryattin Street

Views of pre-revolutionary Lubny: left to right, Market Square, Market St and Piryattin St.

Pre-revolutionary pictures of Lubny (above) show a market square called variously “Bazaar square” or “Market Square” with a huge church behind it. The square is still there but the church has gone. The market is now a covered building and in the streets on either side are a mass of baboushkas selling fruits and vegetables of bright colours, unpasteurised milk in reused plastic bottles, cheeses and sour cream. Otherwise, much of the centre of Lubny has suffered from the ravages of the 20th Century. In turn these were the Revolution, early Soviet industrialisation and redistribution of properties, Stalin’s famine, the German occupation of 1941-1943, the retaking of the City by the Red Army and then postwar reconstruction. Thus, if one wants to find Tsarist Lubny, one has to look for it. The village of Kruglik itself has disappeared, at least from the map, where it is unromantically named “Microregion № 8”, but Kruglik itself exists in the street names and in the conversation of the locals.

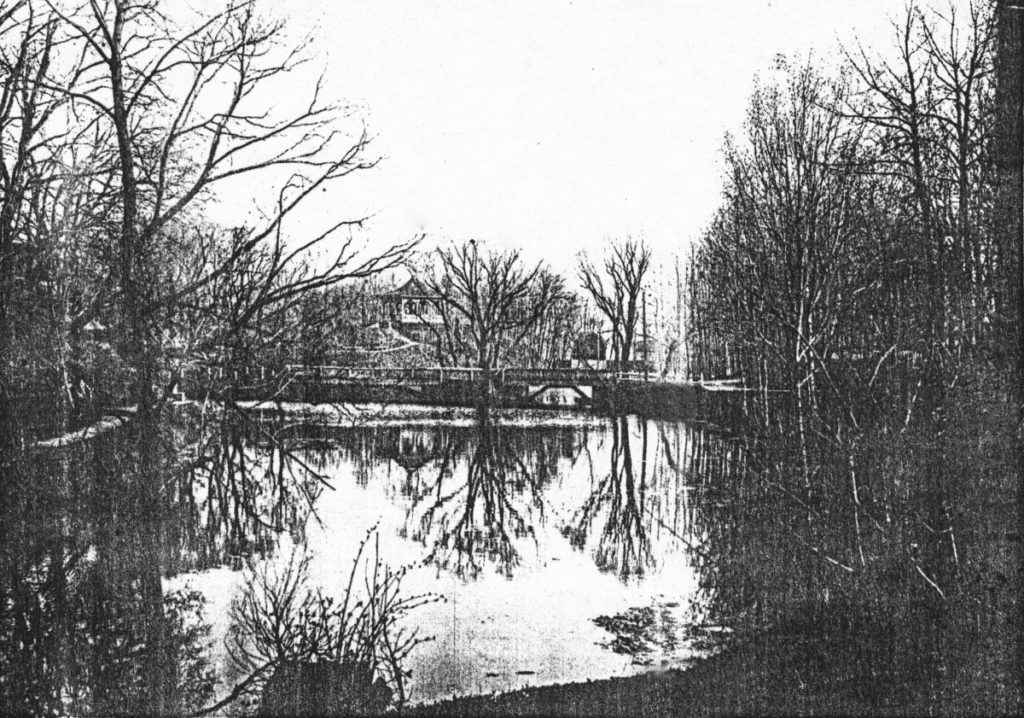

I saw two routes to Kruglik on the map and so took what appeared to be the most logical of the two but which turned out to be very much of a back route. This was a walk of about 45 minutes along a straight road called “Olexandria” leading out from close to the market square. Then along a dusty unmetalled road, similar to Vulitsa Katerina Skarzhinska, called Kruglik Road. This steadily became more and more rural, with chickens on the road, and, being distracted, I became lost in a series of tracks called First Kruglik Lane, Back Kruglik Lane, Second Kruglik Lane, Kruglik cul-de-sac and so on. Heading down a dip into what looked like a sunken bridleway, a man in a filthy open shirt, pushing a bicycle passed me in the other direction. I asked the way to the Kruglik Pond (Kruglitsky stavok) and he pointed ahead. Eventually we came out on the south side of the pond, the lake where Vassili ducked the unfortunate drunkards on Thursday afternoons. This was quite beautiful with men fishing in the pond. I stopped at the village shop for a bottle of beer and asked if they could tell me where the Estate stood. “Somewhere near the school”, I was told,

Kruglik Pond, then and now

The historic centre of Kruglik is by the north east corner of the Pond. Along the north side runs Kiev Road, and there is a Second War memorial and a modern cemetery there. The memorial commemorates 94 soldiers and 50 villagers killed during the time of the occupation. While many surnames occurred more than once, there was no Skarzhinska or Klimov.

On the north west side is the school which Katerina founded in 1888. It bears a plaque to her, but no one there could tell me where the Estate lay. They thought it was near the territory of the school, but more likely just beyond where the 20th and 21st century arrive back with a brutal jolt. There is a car parts factory, an electrical substation, a police pound and a row of ugly, five storey “Krushevka” apartments. My experience of Soviet aesthetics would tell me that it was somewhere under this lot. I gave my empty beer bottle to a babouska who was scavenging through one of the skips outside the apartment block – she will get 25 kopecks for it – and walked back to the town, a dreary walk of about an hour along the main road, past the bus station and past the railway station.

My final visit was to the District Museum, which was in Yaroslav Mudry St and which had been closed in the morning. It was still closed, and I was only there for some 10 minutes, but was shown the pictures which they had of the Estate, and various other items of interest, and made the necessary contact to receive the rest by correspondence. Nobody there knew anything of Bax, nor had Natalia been of much interest to anyone as the charitable work had been continued by Olga.

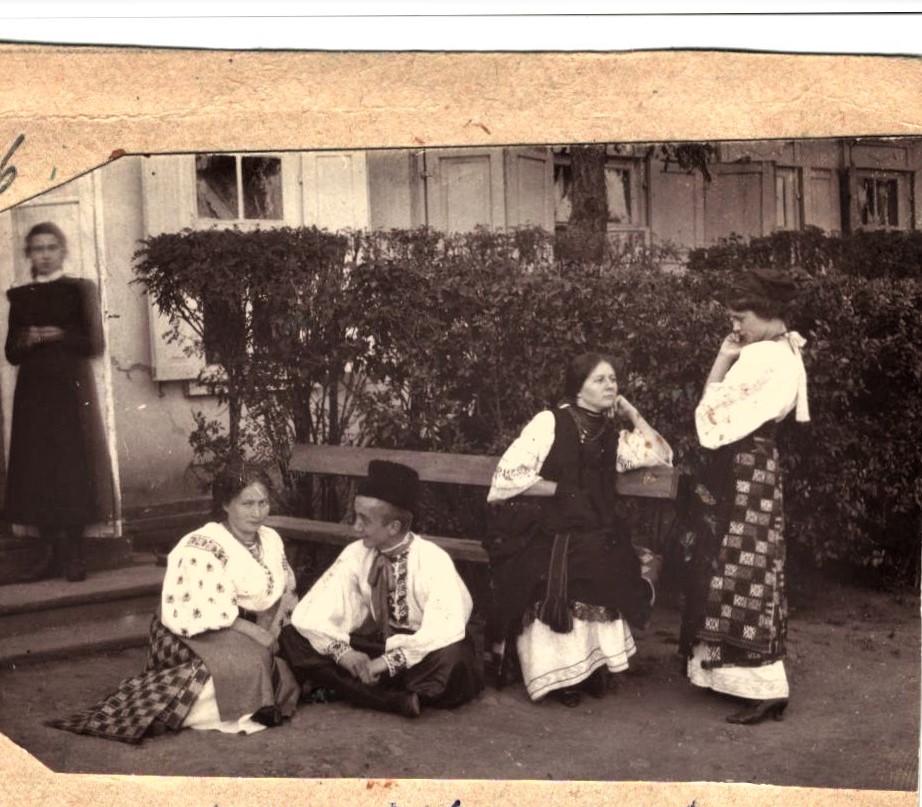

Below are a series of photographs of the Skarzhinska Estate taken approximately 1900-1910 which they provided. There are no notes as to who are the people visible in them.

The older wooden house on the Estate, where was Bax’s apartment. Note the cottage to the right which forms the background of the photographs of Natalia.

The main residence, described by Bax as a “building of more modern construction”

Various views

Excursions and impressions

Bax never did seem to care for folk music and this continued in Ukraine. He did not show any interest in the folk songs sung by the peasants at work in the fields: “almost all day long the lovely birchwoods resounded uneasily to the hideous howling chants without which the women amongst the Ukrainian field labourers seem incapable of working, even in their own dilatory way”. But he comments on the atmosphere of a May night and on the clarity of the sky (I can confirm these myself) The only excursion which Bax mentions is the trip to Kiev with Lvof Pavlovich Klimov to obtain the piano. I find it odd that he did not visit either Poltava or two other nearby villages of interest to an artist. These are Dikanka, near Poltava, recorded by Gogol, and Soroshchinsky, also in Poltava district, made famous by Moussorgsky. But Bax’s account of his stay in Ukraine is only partial: there is no record of the return journey for example, so as for what are the impressions about which Bax otherwise speaks are just a matter for conjecture.

So, other than the humiliation of the whole episode, what did Bax gain from his stay in Ukraine? “May night” is obvious and is dedicated to Natasha and Fiammetta. Bax does not mention whether he took part in the Thursday visits to Lubny, but must have gained some impressions to remember the rhythm for the Gopak, and for the atmosphere of “In a vodka shop”, although these were both written later. Much of his time would have been spent on the First Piano Sonata and First Violin Sonata, and he would also appear to have spent much time on the F major symphony which in the event was never published. Then again, in “Farewell, My Youth”, he appears to have spent much of the stay being unable to write. Meanwhile, I have my own ideas about the First Sonata: given that it was written originally as a “Romantic Tone Poem”, would not the first subject represent Bax’s own personal anguish while the second would be Natalia?

Do look at the pictures. You will see that Natasha’s hair is not gold-spun, but the picture of the three siblings taken five years before is interesting as the eyes of Natasha do have a certain look to them – that of the “Roussalka” which Bax calls her.

Natalia Skarzhinska (right) with members of the Klimov family 1912. The picture is marked “Thus we spent summers at Kruglik”.

Kruglik village (north of the pond) and villagers

And here are my offerings, the two “Russian” pieces.

Sources consulted:

- UK.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Скаржинська_Катерина_Миколаївна

- Olga Ilchenko (Poltava): “Women’s Patronage in Ukrainian Education” (Jnl of Pedagogical Science 2016)

- Olga Ilchenko “Women’s welfare, Katerina Skarzhinska and the Lubny National Education Movement” (same, 2015)

- A. Suprunenko “Archaeology, the activity of the first private museum in Ukraine”

- P. Batievsky “History of the Kruglik school”

- Black and white photographs and postcards from Lubny District Museum