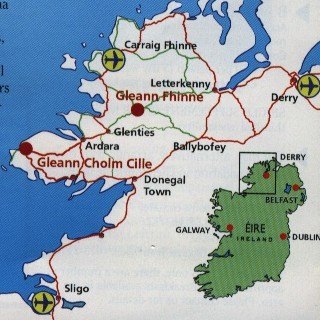

Following Bax to Glencolumcille – by Ian Lace

Following Bax to Glencolumcille

by Ian Lace

THE SIR ARNOLD BAX WEB SITE

Last Modified June 22, 2003

Editor’s Note: There are numerous spellings of Glencolumcille but we have chosen to include only the more modern accepted spelling for the sake of consistency.

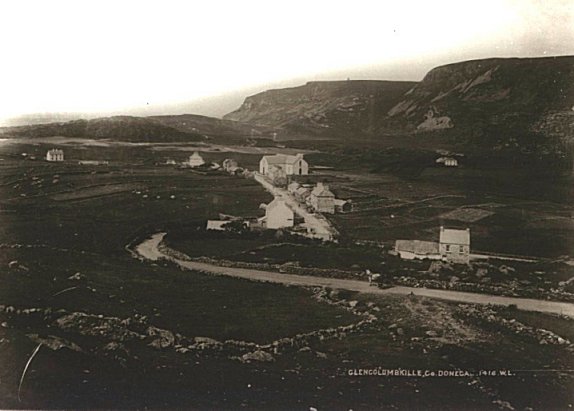

Photo of Glencolumcille taken about 1908

‘I like to fancy that on my deathbed my last vision in this life will be the scene from my window on the upper floor at Glencolumcille, of the still brooding, dove-grey mystery of the Atlantic at twilight; the last glow of sunset behind Glen Head in the north, with its ruined watch-tower built in 1812 at the time of the scare of the Napoleonic invasion; and east of it the calm slope of Scraig Beefan, its glittering many-coloured surface of rock, bracken and heather, now one uniform purple glow.

‘In winter I would often linger at that window, too fascinated in watching the implacable fury of that same Atlantic in a south-westerly storm to sit down to work. At one end of the little Glen Bay was a wilderness of tumbled black rocks, for some reason named Romatia (a particularly ‘gentle’ – or fairy-haunted place, I was told in Dooey opposite), and upon this grim escarpment the breakers thundered and crashed, flinging up, as from a volcano, towering clouds of dazzling foam which would be hurled inland by the gale to put out the fires in the cottage hearths of Beefan and Garbhros. The savagery of the sea was at times nearly incredible. I have seen a continuous volume of foam sucked, as in a funnel, up the whole six-hundred-foot face of Glen Head, whilst with the wind north-west a like marvel would be visible on the opposite cliff… One evening I saw over Glen Head the most astonishing and beautiful aurora borealis imaginable. Swords and spears of red and gold poured down the northern sky, with fan-like openings and closings of the heavens ’

‘…To the day of my death, and I hope afterwards, I shall continue to bless and love Glencolumcille and ‘the best people in Ireland’.

– Arnold Bax, Farewell My Youth

In May 2003, my wife and I travelled to Glencolumcille in County Donegal – a remote place greatly loved by Sir Arnold Bax – a place that influenced so much of his music. This article first recalls Bax’s experiences there, and then covers our impressions of the ‘Glen’ today.

The old church in Glencolumcille (photo top) and nearby Glen Head (photo bottom). Photos by Ian Lace.

Enchanted by Ireland

‘The Celt has ever worn himself out in mistaking dreams for reality,’ but I believe on the contrary, the Celt knows more clearly than the men of most races the difference between the two, and deliberately chooses to follow the dream.’

In his autobiography, Farewell My Youth, Bax recalled –

‘I went to Ireland as a boy of nineteen (1903) in great spiritual excitement, and once there my existence was at first so utterly unrelated to material actualities that I find it difficult to remember it in any clarity.

‘I do not think I saw men and women passing me on the roads as real figures of flesh and blood; I looked through them back to their archetypes, and even Dublin itself seemed peopled by gods and heroic shapes from the dim past.

‘But I spent most of my time in the west, always seeking out the most remote corners I could find on the map, lost corners of mountains, shores unvisited by any tourist and by few even of the Irish themselves.’ [He goes on to mention many places in Counties Galway and Donegal.] … ‘But for me all these faraway places were alike bathed in supernal light. … I worked very hard at the Irish language and steeped myself in history and saga, folk-tale and fairy-lore’…Under this domination, my musical style became strengthened and purged of many alien elements. In part at least I rid myself of the sway of Wagner and Strauss and began to write Irishly, using figures and melodies of a definitely Celtic curve…’ [although] ‘I should like to put it on record that only once in my career as a composer have I made use of an actual folk-song.

‘…Yeats was the key that opened the gate of the Celtic wonderland to my wide-eyed youth, and his was the finger that pointed to the magic mountain whence I was to dig all that may be of value in my own art… Al the days of my life I bless his name. ’

Bax’s first trips to Ireland were made in the company of his brother Clifford. At the beginning of the 20th century, the far west of Ireland was already established as a tourist attraction, though lack of high-class facilities, particularly in Donegal to which Bax went, meant that some parts were little known and therefore very wild and cut off. The young Baxes travelled by rail, where it was available, but much of their touring would have been by bicycle. The village of Glencolumcille was soon discovered in West Donegal. It was to be Bax’s spiritual home for the next thirty years. Bax quickly came to regard ‘Glen’ as home and a safe retreat from all the worldly troubles that beset him finding, the ‘most amazing peace’ there.

Glencolumcille

Quoting from Lewis Foreman’s, Bax, A Composer and His Times: ‘Glencolumcille’s very remoteness must have underlined the attraction of this tiny community, set in a gently sloping valley facing the Atlantic but rising to high and awe-inspiring cliffs on either side. Arnold revelled in the savagery the Atlantic brought to the country of West Donegal. No fair-weather traveller, he found a personal serenity in the fact that that wild beauty is rarely comfortable or comforting, and he experienced a fierce exultation in the primitive and untamed which was later to be reflected in his music. He established an enduring and affectionate relationship with the inhabitants of Glencolumcille, many of whom are delightfully drawn in his autobiography, including Paddy John McNelis the publican, seated outside his door on a pile of empties; the tapping of lame John Gillespie; Cormac Molloy, the weaver; old Peggy, Paddy John’s wife, her figure almost as round as she was high; and other wilder characters from the district…. In a letter written to a girl friend in 1903 or 1904 from the Glencolumcille Hotel, Carrick, Bax wrote of the Ireland that ‘as usual is all so heart rending and so beautiful and she seems more like a living being to me than ever…I bury my face in the grass and dream fiercely in the dear brown earth…What of Irish Dermid (Bax himself) and his homeland…I wonder if I should seem the same through the peat smoke and blue mists of Eire. This is the real Dermid at any rate and the English edition is only a reprint somewhat soiled and very much foxed.’

Of course Bax was also inspired to write prose as well as music at Glencolumcille. (He wrote poems, stories and plays and writings on cricket and music). In fact his pseudonym, Dermot O’Byrne, first used in 1909 with the collection of his poems called Seafoam and Firelight, may well have been inspired by place-names in the district near Glencolumcille – Rathlin Óbirne Island is just off the coast at Malin Beg, while funeral mounds for Diarmuid and Grainne are nearby.

[Included in the 1992 Scolar Press edition of Farewell My Youth and other writings by Arnold Bax edited by Lewis Foreman is Bax’s story Ancient Dominions which is set in Glencolumcille. It is tempting to think that the cottage, with the magnificent uninterrupted view of Glen Head in which the storyteller lodges as the story opens, is the one pointed out to us as Bax’s actual lodging, on the opposite side of the road where the Glencolumcille Folk Village Museum now stands. The storyteller relates his experiences following a peasant to the top of Glen Head and discovering a secret stairway down through the cliff to witness an ancient pagan sea worshiping ceremony presided over by the peasant he had followed now dressed as an arch-druid. Lewis Foreman attributes this story as a possible influence on passages in Bax’s First Symphony]

Bax lodged in this cottage (left) which has an uninterrupted view of Glen Head. It is situated directly opposite the Glencolumcille Folk Village Heritage Museum. ‘Roarty’s at Glencolumcille (right), the pub where Bax took lodgings. His room (the left hand first floor window at the end of the house) looked over towards Glen Head. The left upper window on the side of the pub is that through which Bax looked over towards Glen Head (see quotation that opens this article). Photos by Grace Lace.

One of the earliest musical works written at Glencolumcille was the String Quintet completed in 1908 the same year that Bax wrote Into the Twilight. Later, in 1910, he was there to write Roscatha (‘Eire Part 3’), dedicated to the ‘Mountainy men of Glencolumcille’.

By the end of the 1920s and early 1930s, however, Bax was beginning to look elsewhere for his inspiration – towards Morar in North West Scotland. But in September 1929 Bax was in Glencolumcille where his thoughts turned to a new relationship with the young Mary Gleaves. [Interestingly I can find no mention of Bax’s other great love, pianist Harriet Cohen in connection with Glencolumcille. It will be remembered that Arnold left his marriage for Harriet with whom he had a passionate love affair during and after the First World War.] In his passionate love letters to Mary he writes, “…This glen faces out west to the Atlantic, and there is a small bay with a lovely strand where I bathe every day…You would love the gentle innocent people. I think it is a great privilege that they regard me as one of themselves…Oh little Mary, darling, I would like to put some enchantment on you and bring you here in dream if it can’t be done in reality, because I believe it is just this mood that would help you [Bax had provided help and sympathy the previous year when Mary’s father was dying of cancer and her mother was away and also ill]. This West of Ireland atmosphere is hovering between the world we know too well and some happy other-world that we begin to glimpse when we are growing up and never reach.’

In 1930 Bax appears to have paid only a brief visit to Glencolumcille and although he did continue to go there until at least 1934, 1930 really marked the break with his habit of spending long periods there.

Glencolumcille and Donegal influences on Bax’s music

Bax was in Glencolumcille in the Autumn of 1912 when he received a summons from the poet George Russell (‘Æ’) suggesting that Bax should join him for a week in Breaghy, near Dunfanaghy where he went every September to paint. Dunfanaghy is another faraway place, way north of Glencolumcille at the other side of Donegal. Bax cycled up there via Ardara and the Rosses. It was at Breaghy, staying with ‘Æ’ in a summer house in wooded grounds, above the sea, that Bax experienced something that was to be enshrined in the magical pages that comprise the middle section of the Epilogue of his Third Symphony (1929) –

‘I have not met with many experiences which cannot be accounted for by rational explanation, but one of these occurred in that place in the dripping Breaghy woods.

[Æ was busy painting and smoking his pipe and] – ‘I was reading in the window seat near the door, and we had not spoken for perhaps a quarter of an hour when I suddenly became aware that I was listening to strange sounds, the like of which I had never heard before. They can only be described as a kind of mingling of rippling water and tiny bells tinkled, and yet I could have written them out in ordinary musical notation.

‘”Do you hear the music?” said Æ quietly. ‘I do’ I replied, and even as I spoke utter silence fell. I do not know what it was we both heard that morning and must be content to leave it at that.

‘As the dusk deepened many-coloured lights tossed and flickered along the ridges of the mountains. “Don’t you wish you were amongst them?” murmured Æ, and I knew he meant that we were gazing upon the host of fairy. Even under the spell of that lovely hour and with an intense will to believe it seemed to me probable that those dancing shapes of flame were something to do with the retinae of my own eyes straining into the semi-darkness and no far-off reality’.

Bax’s Fourth Symphony reflects his happiness and fulfillment with Mary Gleaves. This was written between October 1930 and February 1931, almost entirely at Morar, although ‘part of the first movement at any rate was worked out at Glencolumcille.’ It was to be a farewell.

Although it is more associated with Morar, Bax’s Fifth Symphony (1932), one of Bax’s most personal and characteristic scores, dedicated to Sibelius, could, nevertheless, have been influenced, in its slow movement, by Slieve League a favourite place of natural grandeur in the west of Ireland [close-by Glencolmcille]. As Lewis Foreman writes: ‘The brilliant pictorial opening to the slow movement – high tremolandi on the strings, running harp colouration and fanfaring trumpets – is breathtaking when first heard and makes one think of some long-cherished grand sweep of landscape. In a book review Bax referred to the sensation of suddenly seeing the sea at the summit of Slieve League. To “anyone going up from the south”, he wrote, “the sea is hidden by the landward bulk of the mountain itself, so that when it bursts into view at a height of almost two thousand feet, the sudden sight of the Atlantic horizon tilted halfway up the sky is completely overwhelming.” It is some such experience that was being remembered in the splendid and evocative opening to this passionate but autumnal movement.’

Although it is more associated with Morar, Bax’s Fifth Symphony (1932), one of Bax’s most personal and characteristic scores, dedicated to Sibelius, could, nevertheless, have been influenced, in its slow movement, by Slieve League a favourite place of natural grandeur in the west of Ireland [close-by Glencolmcille]. As Lewis Foreman writes: ‘The brilliant pictorial opening to the slow movement – high tremolandi on the strings, running harp colouration and fanfaring trumpets – is breathtaking when first heard and makes one think of some long-cherished grand sweep of landscape. In a book review Bax referred to the sensation of suddenly seeing the sea at the summit of Slieve League. To “anyone going up from the south”, he wrote, “the sea is hidden by the landward bulk of the mountain itself, so that when it bursts into view at a height of almost two thousand feet, the sudden sight of the Atlantic horizon tilted halfway up the sky is completely overwhelming.” It is some such experience that was being remembered in the splendid and evocative opening to this passionate but autumnal movement.’

Slieve League

Incidentally, although the influences are located further south in the Kerry countryside, and Mount Brandon at the northern end of the Dingle peninsular, together with W.B. Yeats’ writings, it is interesting to note what drove Bax’s In the Faery Hills (An Sluagh Sidhe – ‘Eire – Part 2) (1909). Bax recalled, ‘I got this mood under Mount Brandon with all W.B.’s magic about me.’ And, in a programme note, Bax declared that he had attempted to ‘suggest the revelries of the ‘Hidden People’ in the inmost depths and hollow hills of Ireland’. At the same time he ‘endeavoured to envelop the music in an atmosphere of mystery and remoteness akin to the feeling with which the people of the West think of their beautiful and often terrible faeries.’ The middle section of the work (writes Lewis Foreman) is based to some extent on a passage in The Wanderings of Usheen, the Yeats poem which had first drawn Bax to Ireland. In it the Danaan faery host bid a human bard sing to them, but his song of human joy is the saddest they have ever heard; flinging his harp into a deep pool they whirl the harper away with laughter and dancing.’ Similarly Bax’s Into the Twilight (‘Eire – Prologue’) (1908) prefaced by Yeats’ poem, according to Bax, ‘seeks to give a musical impression of the brooding quiet of the Western Mountains at the end of twilight and to express something of the sense of timelessness and hypnotic dream which veils Ireland at such an hour.’

Clearly it is likely that Bax would have worked on parts of many other compositions during months of the many years that the composer spent in Glencolumcille. Although, for instance, The Garden of Fand (1913, orchestrated 1916) was written in Dublin and London, the opening pages are so wonderfully evocative of a shimmering, glistening, still Atlantic, that one is tempted to imagine Bax sketching these pages at Glencolumcille.

Glencolumcille – 2003

We travelled across Ireland on the N4 from Dublin and spent some time at Sligo visiting the Yeats Memorial Building that houses the Yeats Society and the Sligo Art Gallery to see the Yeats memorabilia. Across the Hyde Bridge is a statue of the poet. Travelling north towards Ballyshannan and Donegal we stopped at Drumcliff in the shadow of the mighty Ben Bulben to pay our respects to WB Yeats who lies in the churchyard. His burial stone has the last lines of his poem, Under Ben Bulben –

Cast a cold eye

On life, on death

Horseman, pass by!

– and outside there is a large memorial quoting in full, He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven, ending in these famous lines –

But I being poor, have only my dreams;

I have spread my dreams under your feet;

Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.

At Donegal we turned towards the west and Glencolumcille passing the small fishing port of Killybegs and thence over a twisting narrow undulating road passing over moorland dominated by the vast bulk of the mountain that is Slieve League on its landward side before plunging down the steep hill into the Glen.

As we drove along, I remembered how Bax described the journey in Farewell My Youth: ‘When I was young there were two ways of getting to Glencolumcille. One was from the railhead at Killibegs, a decayed little port, pretty enough in a rather shabby style…thence it took you a mere matter of three hours on a ‘jaunting-car’ (horse and cart) to cover those seventeen miles to Glen…or you could go from Glenties, the terminus of the Donegal light railway from there you had twenty-three miles and four-and-a-half hours drive before you. Even in winter I always chose that route… There was no cover whatever on the now almost extinct ‘jaunting-car’ and sometimes I found myself on a puddled seat even before I reached Ardara, to face Glengesh (a pass scheduled by the R.A.C. as impassable for motors)….Nowadays (he was writing in Storrington, Sussex in 1943), a small motor-bus runs from Killybegs carrying the mail-bags which almost fill the interior, and allowing comfortable room for two passengers only, although sometimes five or six are somehow crammed into it. (I have known what it is to be the seventh.)’

We journeyed through Glencolumcille and noticed how much it had developed since Bax’s time with many new dwellings reflecting the Irish Republic’s general prosperity due to generous EU funding. There is even an organisation now called Glencolmcille Holiday Homes. (Int. Tel: 00353 74 9730132) Our destination was the large modern Hotel Gleann Cholm Cille (just another of its many different spellings) situated round the headland to the south of the Glen, where we stayed for three nights. [Note the B&Bs now springing up in the Glen are more recommendable].

The following morning dawned misty and drizzling but we elected to walk into Glencolumcille past Glen Head grey-black and brooding in the mist. Our first call was at the splendid Glencolumcille Folk Village Museum that depicts rural Donegal lifestyles through the ages. It was started by a local priest, Father James MacDyer (1910-1987). Concerned about the high rate of emigration from this poor region, he sought to provide jobs and a sense of regional pride, partly by encouraging people to set up croft cooperatives. The Museum itself includes typical, very basically furnished cottages, with open fires equipped with tackle to smoke fish etc, that would have been occupied by fishermen/peasants, and a larger more comfortable abode for the local priest. There is also a schoolroom that has many fascinating old photographs displayed on its walls. One building houses displays charting the history of Glencolumcille from the stone and iron ages through the arrival of Christianity with Saint Colmcille (as the locals call him or St Columba) to modern times. My transcriptions of those displays relating to the myths and legends associated with Glencolumcille that must have fascinated and influenced Bax, are appended at the end of this article.

There is plenty to explore in the valley, which is littered with cairns, dolmens and other ancient monuments.

Hoping to discover more about the Bax connections, we visited Oideas Gael, the college that offers courses for adults in Irish Language and Literature (Int. Tel: 00353 73 30248) situated just a little way along the road from the Folk Village Museum. The Language Director, Liam Ó Cuinneagáin, told us that a BBC team had just rung him to enquire after somebody with local knowledge who could guide them when they came to prepare material for broadcast later in 2003 (the 50th anniversary of Bax’s death, see my article Bax’s last golden twilight – Bax’s last excursion from Cork to the Old Head of Kinsale.)

Liam recommended that we visit Roarty’s Bar, the pub in which Bax lodged further up the road in Cashel, Glencolumcille. Here the publican, James Byrne made us most welcome. In his bar, James has a special glass case devoted to the memory of Bax. It contains a very good pencil drawing of Bax, by a local artist with the quotation from Farewell My Youth that opens this article. Opposite is a portrait of the Irish patriot, Padraig Pearse Below that is a copy of Farewell My Youth open at page 92 in which Bax recalls meeting Pearce and Molly Collum (Padraic Colum, the Irish poet and playwright’s wife) saying to him ‘“Pearse wants to die for Ireland you know. It has been his ideal all his life.” Indeed he did not have much longer to wait before his desire was granted.’ [Pearse was shot after the abortive Easter uprising in Dublin in 1916 – an event that shook Bax and greatly affected his music.]

James Byrne remembered his mother’s recollections of seeing Bax writing on the beach and near a waterfall. Mr Byrne was also kind enough to show us the actual room Bax stayed in and the window from which he looked across towards Glen Head (see quotation at the head of this article).

One sunny evening we hired a taxi to take us out to Slieve League. We persuaded Herbert, an eighty-six year old fellow traveller to accompany us. Herbert had been born in the area and had attended an Irish language school in Carrick. He well remembered being influenced by the folklore of the region when he was a child. He told us that one night he lay in fear of his life when he had castigated the faeries. He really feared that he heard outside, the wailing of a banshee, a female spirit with long flowing hair signalling his imminent demise. We approached the highest cliff face in Europe over the bumpy 8-km (5-mile) drive to its eastern end from Carrick, over Bunglass Point, with precipitous drops on the seaward side of the narrow road for much of the time (not recommended for those suffering from vertigo!).The view in the golden glow of that sunset was magnificent. Herbert quite rightly reminded us that the best view of Slieve League to get a full impression of its grandeur and great height, was from the sea by small boat (one can be hired at nearby Teelin). We also had a clear view back to the south east towards Sligo of the massive form of Ben Bulben, looking like a long sphinx, dominating the distant horizon.

In conclusion we are delighted to report that our visit to Glencolumcille seems to have initiated the idea of a small Bax Festival there at the beginning of October 2004. Feasibility studies are proceeding. Watch this space.

Appendix – Material fr om Glencolumcille Folk Village Museum

Glencolumcille – Fairy Music

The most ancient form of music here was played on the harp and the warpipes… The fairies were pipers of marvellous ability in circumstances both sinister and appealing. A red-haired piper playing on a ledge near the foot of Sliabh liag (Slieve League) once, nearly distracted fishermen from an oncoming storm. Another fairy piper once led a Poitin*-maker home through impenetrable mists on the landward side of the same mountain. (*Poteen or potheen is an Irish whiskey illicitly distilled, especially from potatoes.) While the fiddle has become the most popular instrument in Glencolumcille, the pipes were very active in the 1900s at events such as the night of then Bealtaine (May 1st).

Fairies and Ghosts and Christianity

As the Roman Catholic Church gained strength in the 1820s, bishops and parish priests targeted many customary rural beliefs. Anything undisciplined came under suspicion as non-Christian or pagan, even popular devotions as holy wells. The people themselves did not see their beliefs in fairies, charms and wakes, as incompatible with the Christian faith; and it should be possible now to see that these pieties added to their religious vision and were not in conflict with it.

Until 1834 when Cornelius McDermott PP organised the erection of a chapel at Cashel in Glencolumcille, Mass was said in the open air, at various Mass-rocks or at ‘stations’ in certain houses. Preaching was in the Irish language. There was much prayer as well as entertainment at the festivals at holy wells.

Every foot of land, pasture, arable or bog was soaked in folklore, and was as such a part of the “other world” of fairies and ghosts as much as the mundane world of markets and rent and subsistence. Fairies were thin-blooded creatures, red-haired, about 2 feet tall, wore red caps, smoked pipes and were fond of music and capering dances. If treated with courtesy, fairies could help home and farm; but if wronged – by tossing dirty water on their courts or spoken of with disrespect – they could destroy a man’s luck and steal away his wife or children.

Colmcille banishes the demons from the old Glen.

Colmcille (St Columba) needed his fearsome temper to get rid of the demons holding the Sean Ghleann (old glen) under sway. One day he and others came to the demons’ stream of fire guarding the Glen. A demon tossed a spear out of the mists and killed Cerc, the servant of Colmcille. The saint angrily hurled it back breaking up some of the fog. The stream lost its evil power once blessed by Colmcille. Leaping across it he volleyed a green stone at the slinking demons. The demons retreated in pain once Colmcille threw his holy bell at them. As they hovered over the sea, Colmcille finished them off by turning them into red-eyed sea creatures. In a spinning ball of fire the bell and the stone came back to the saint.

© Ian Lace, 2003

Thanks to the Estate of Sir Arnold Bax for permission to reproduce extracts from Bax’s

autobiography, Farewell, My Youth, which is the copyright of the Sir Arnold Bax

Estate.