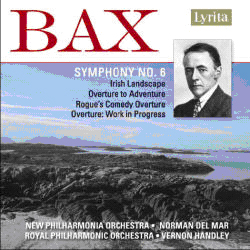

Del Mar’s Classic Bax Sixth along with new Handley overtures on Lyrita – Review by Graham Parlett

Bax: Symphony No.6*, Irish Landscape, Rogue’s Comedy, Overture to Adventure, Work in Progress.

*New Philharmonia Orchestra, Norman Del Mar; Royal Philharmonic Orchestra,Vernon Handley.

Lyrita SRCD 296. Duration: 75:43.

THE SIR ARNOLD BAX WEB SITE

Last Modified August July 13, 2007

Reviewed by Graham Parlett

Norman Del Mar’s performance of No.6 was only the third commercial recording of a Bax symphony. It came out on LP in 1967, at a time when the composer’s reputation was at its lowest since his death, and was partlyresponsible for generating renewed interest among a younger generation of listeners. It was the first performance of the work that I had ever heard, and listening to it again in this excellent new reissue I was able to rekindlesomething of the pleasure which it gave me at the time. Del Mar takes the opening tempo much faster than Bax is believed to have intended, but then so do most other conductors, and I am not sure that it really works when played too slowly; Bax was no conductor himself, and Moderato is, after all, a rather vague tempo marking. The vigour with which he attacks the Allegro con fuoco is most exhilarating, sweeping us into the Sturm und Drang of Bax’s shortest and most concentrated symphonic first movement. I like the way DelMar keeps the music moving ― something that not all conductors achieve when conducting Bax ― and yet the more reflective passages do not sound at all hurried. The final page, with its exhilarating sense of release, is played, as it should be, with great force and decisiveness.

The first two movements of this symphony were originally conceived as part of a second Viola Sonata, and it is easy to imagine how the rich melody heard near the start of the slow movement would have sounded in this form. Del Mar takes the movement more slowly than Handley in his recording for Chandos and shapes the music most eloquently, pressing on where necessary and then relaxing as appropriate. That bracing section starting around 6:09, which always reminds me of the sea crashing against rocks, has never sounded better, andthe dissonant march-like passage starting at 7:05, with its grinding bass, is as powerful as it should be. I was expecting to hear some residual tape hiss from this forty-year-old recording at the hushed close of the movement, but I am glad to report that there is very little.

The first two movements of this symphony were originally conceived as part of a second Viola Sonata, and it is easy to imagine how the rich melody heard near the start of the slow movement would have sounded in this form. Del Mar takes the movement more slowly than Handley in his recording for Chandos and shapes the music most eloquently, pressing on where necessary and then relaxing as appropriate. That bracing section starting around 6:09, which always reminds me of the sea crashing against rocks, has never sounded better, andthe dissonant march-like passage starting at 7:05, with its grinding bass, is as powerful as it should be. I was expecting to hear some residual tape hiss from this forty-year-old recording at the hushed close of the movement, but I am glad to report that there is very little.

The finale, which, uniquely among Bax’s symphonies, opens quietly, with a clarinet solo, is one of his most concise and formally perfect, and it is a pity about the studio noises that can be heard (if you listen on headphones) as the soloist eloquently plays the composer’s sinuous melodic line. The difficult transition between the Introduction and the Scherzo ― a gradual acceleration from Lento moderato to Allegro vivace ― is managed very well here, as it is on most of the other recordings, and Del Mar brings a delicious sparkle to the music. The awkward transition from the Scherzo is also carried off with aplomb, and I especially like his pacing of the Trio section that follows. All the other versions seem to me to be too slow here, whereas he moves the music on to good effect. The climax of the movement ― of the symphony ― of the whole cycle of symphonies, as some believe ― is a tremendous moment: the ‘passing of worlds’, as Peter J. Pirie calls it in his notes. To be honest, I am not sure that any of the performances that I have heard of this work have achieved the transcendental quality that Bax was presumably aiming for, and perhaps the music requires some kind of extra dimension ― the kind of thing that Mahler strove to achieve in the finale of his own Sixth Symphony with its convulsive hammer strokes. The entry of an extra orchestra at this point might do the trick, if the work were ever played in Cloud-Cuckoo-Land; or, as Bax remarked in respect of Bruckner’s Fifth Symphony, ‘an army corps of brass instruments….crouching furtively behind the percussion….’ might be employed for this climactic moment. Nevertheless, the New Philharmonia and Norman Del Mar make a good stab at it, though the sound seems unfocused and the trumpet solo fails to cut through the texture as it should. This is the one place where both Handley and Lloyd-Jones are definitely more effective. The epilogue is very well managed, though the recording artificially highlights the horn solo, but it is good to hear the last few pages without the awful snap, crackle and pop that accompanied them at this point on copies of the LP. The original recording was not one of Lyrita’s best, I recall, and I was surprised at how much better it now seems, thanks no doubt to the skill of Simon Gibson, who has done the transfers. It may seem a little hard and unyielding in places and lacking in what record-reviewers call ‘bloom’, but there is nothing to interfere with one’s enjoyment, and the performance on the whole remains for me the best of the lot, despite that underwhelming climax. It is a pleasure, after forty years, to be able to welcome this pioneering recording back into the catalogue.

Irish Landscape is the second of Bax’s Three Pieces for Small Orchestra, a 1928 revision of the Four Orchestral Pieces of 1912-13 but without the final Dance of Wild Irravel; it was originally called In the Hills of Home or From the Mountains of Home. Scored for strings and harp, it is one of Bax’s most heart-felt Irish miniatures and receives a loving performance from Handley and the RPO. (There are a few missing pizzicato notes near the beginning, but this is a mistake in the copyist’s score and parts that are always hired out, and it occurs in the only other commercial recording, from the English Chamber Orchestra under Jeffrey Tate on EMI.) Handley’s version was originally issued on an LP entitled ‘More Lyrita Lollipops’, together with short works by Alwyn, Berners, Grainger, Leigh, et al., and it is good to have it available again. The sound is full and rich but a little mushy, and Handley has obviously used a larger body of strings than Tate on his recording.

Rogue’s Comedy (‘Overture’ is not actually part of the title) dates from 1936 and bears a close kinship with the much more familiar Overture to a Picaresque Comedy of 1930, which Bax referred to in letters to Harriet Cohen as his ‘Douglas Fairbanks Overture’ and which was actually played through at the recording sessions in 1994, though in the end it was decided that there was insufficient time for both it and Work in Progress to be recorded. The jaunty opening theme on woodwind is reminiscent of one from the ‘Emperor’s Court’ scene in Kodály’s opera Háry János, written ten years earlier, at about the time the two composers became personally acquainted; it is not known whether this resemblance is intentional or coincidental. After a short woodwind fanfare (with the rattle briefly making a public nuisance of itself), a new theme on trumpets injects a martial note into the proceedings. The slower middle section introduces three more themes, and development of all this material ensues, with the anonymous rogue (Scapino? Scaramouche? Till Eulenspiegel?) engaging in mock heroics and perhaps a romantic dalliance before a moment of sober reflection prepares the way for the uproarious ending. Vernon Handley recorded the three overtures on this CD in January 1994, but they have had to wait thirteen and a half years for their release. This version of the overture has thus appeared a few years after his second recording of the work (for Chandos, as part of the set of complete symphonies). I made a direct comparison between the two and found that the Lyrita performance is more relaxed, less hard-driven than the Chandos one (it is actually about a minute slower), and I am glad that Handley does not make quite such a marked accellerando at the end of the piece as in his later version. The Chandos sound is richer and beefier than the Lyrita, but the latter has greater clarity and bite.

Although Handley’s performance of the Overture to Adventure was the first to be recorded, Douglas Bostock’s, with the Munich Symphony Orchestra (on the Classico label), was the first to be issued, coupled with a decent, but not outstanding, version of the Sixth Symphony and a performance of Tintagel which I rather liked, though others were less enthusiastic about it. Bostock’s performance of the overture, however, never sounded much more than a play-through of the score, and the speed he adopted for the slower section was, in my view, too lethargic. Handley, in contrast, moves the music along, and I much prefer his full-blooded approach: this is the kind of piece that needs to be played with total conviction rather than half-heartedly. Bax himself never thought much of the score (‘a second rate overture’ he called it), and it is curious that he submitted it for publication when the ink was barely dry on the page. The opening rhythmic figure is strongly reminiscent of a theme in the finale of Glazunov’s Fifth Symphony, and the slower section contains a warm but strangely subdued melody followed by yet another one of Bax’s ‘liturgical’ themes, this one more dour than some. The lively development is full of stirring stuff, and the work emerges as a far more exciting piece than it appeared in Bostock’s hands. The date given for this overture on the back of the booklet (1937) is actually the date of publication; it was completed in October of the previous year.

Work in Progress was Bax’s last overture, written in 1943, and is the lightest and jolliest of the lot; he called it a ‘jeu d’esprit’, and it may remind some listeners of Eric Coates. (Bax was asked to write another for the Festival of Britain in 1951 but was unable to summon up the energy to produce anything.) Like Rawsthorne’s Street Corner and Moeran’s Overture for a Masque, it was commissioned by Walter Legge and the Entertainments National Service Association for a series of symphony concerts for war workers, for which purpose it is admirably suited, being straightforward, lively, and tuneful ― a ‘classical’ counterpart to the kind of music being broadcast on the wireless programme Workers’ Playtime. It was first performed by the LSO under George Weldon at ‘a big factory in the London suburbs’ (name withheld for security reasons during wartime). The overture begins with a syncopated rhythm that recurs throughout, followed by bustling semiquavers, and then a brass theme with repeated notes that has a definite Russian dance flavour, a reminder perhaps that by this stage in the war the Soviet Union was Britain ’s staunch ally. Unusually for Handley, he occasionally makes unmarked rallentandi and accellerandi, and adopts a distinctly slower speed for the ‘lyrical second subject’ (as annotators used to call these things), even though none is indicated in the score. But anyone coming fresh to the piece will accept these tempo fluctuations as being perfectly natural, and the overture receives as effervescent a performance as you could wish; I remember, at the recording session, one of the RPO’s woodwind-players being quite taken with it and remarking on what a good piece it was. Look out too for the brief satirical quotation of a phrase from Deutschland über Alles towards the end of the first section: it is heard first on woodwind and then on strings. Although the overture was often played during the 1940s, the only post-war performance I have traced was a broadcast by the BBC Concert Orchestra under Marcus Dods in January 1969 (recorded the previous June). With the resurgence of interest in British light music, it surely ought to find a place in the repertoire once again.

With Tryggvi Tryggvason as the Recording Engineer it goes without saying that the newer recordings are very good indeed. They are less sumptuous than the sound we are used to on Chandos but, as I have already mentioned, they have the merit of clarity. The eye-catching booklet cover has a fine view of Morar, where three of the scores on this well-filled CD were orchestrated. The notes are by Peter J. Pirie (symphony), Lewis Foreman (Irish Landscape), and myself (overtures), though since I wrote them thirteen years ago I had almost forgotten about them. Although I cannot imagine anyone wanting to listen to three lively (and in the case of Rogue’s Comedy extremely raucous) overtures in quick succession, it is good to have them all in such excellent performances under Bax’s most ardent and prolific champion. And with Work in Progress at last available on disc, there are now very few purely orchestral works by Bax that have not been recorded ― a situation that would have seemed inconceivable forty years ago, when Del Mar’s version of the Sixth Symphony first saw the light of day.