Cuchulan Among the Guns – Reviews

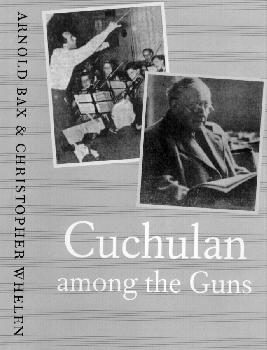

‘Cuchulan Among the Guns’ edited by Dennis Andrews.

THE SIR ARNOLD BAX WEB SITE

Last Modified August 9, 1999

Published by Dennis Andrews,

3 Appleton Road,

Cumnor, Oxford OX2 9QH

United Kingdom.

Further thoughts from Ian Lace

I heartily concur with what Colin and Richard have said in their reviews below. What impressed me just as much as Christopher Whelen’s brilliant insights into the music of Bax was his little vignettes of Bax the man. How sharply he is sketched for us in Whelen’s first meeting with the composer at Bournemouth railway station on a cold February day in 1950 – “…here he was, in a pork-pie hat, and carrying a small suitcase tied up with string…I noticed that above the smile his eyes were wary, that he took small steps and there was a shortness of breath. ‘Can we take a bus?’ he asked. I explained that I had a car waiting, failing to add that it was a battered Rolls-Royce that I thought would add dignity to the occasion. ‘Good God, is that it?’ he exclaimed as we emerged from the station…Tania (Harriet Cohen) is coming down for the concert, do you think we can book this excellent driver and car? She’ll love it’, he added with what looked like half a wink…”

Later, at Christopher’s home Bax is invited to play one of his own works and choses Winter Waters but declines to play it on the grand piano preferring the old upright that the Whelen’s had in their dining room explaining, “‘I never use a grand. I like having a blank wall in front of me.” The next morning they travel by bus to the Winter Gardens (Bournemouth’s concert hall) with Bax insisting that they climb onto the top deck so that he could see the sea even though – “At sixty-five his step was already faltering, his eyes watery and his hand beginning to shake.”

This particular passage is rich in detail and there are some very valuable insights into the performance of Bax’s music. When he asks Whelen how the rehearsals of his Third Symphony are proceeding, Bax remarks, “Dan Godfrey did Tintagel here with only four violins, I forgot what the total size of the orchestra was – twenty I think.’ And later Bax’s modesty comes through as he agrees and bows to the conductor’s interpretative viewpoint, when Whelen rather precociously suggests that the Third Symphony might be more effective with a few tempi modifications.

When I read this wonderful little book (shamefully ignored by the mainstream critics who do not know what they have missed) I was on holiday in Ireland and by a strange coincidence I was in Galway when I read the correspondence between Bax and Whelen when the former recommends places in Eire to visit (Whelen was due to conduct there). Bax’s choice is interesting because it throws light on further Irish influences other than just the Wicklow mountains (south of Dublin) and Glencolumcille. Bax recommends Sligo, Connemara and Galway, Loch Gill and Glencar. “There is nothing quite like Connemara and its magical colours and lights. The blue of the Twelve Pins can be completely other-worldly… I owe my ideas to every part of the west – not only to Glencolumcille – a great deal to Co. Kerry…” Interestingly, Whelan describes Aloys Fleischmann, Professor of Music at Cork, with whom Bax was staying when he died. as ‘a very curious character’. Amongst the many illustrations is a picture of The Old Head of Kinsale, the scene of Bax’s last walk a few hours before he died on October 3rd 1953. Kinsale lies on the coast due south of the City of Cork.

There is also a vivid description of Bax’s routine in retirement at the White Horse in Storrington. “Rising early for breakfast, he is liable to be greeted by another resident with ‘morning Bax, ‘heard one of your pieces on the radio this morning, conducted by old so-and-so,’ to which he will retaliate with, ‘Oh, he’s all right until he starts interpreting the music!’ On days when he doesn’t go to London, he will read books of all kinds (including thrillers as well as poetry) do the daily cross-word puzzle, have a game or two of snooker or visit a nearby friend. In London he might have to attend an official function, present prizes at the Royal Academy of Music where he was once a student, and then if it is the right time of the year, he could spend a couple of hours with his brother Clifford, watching cricket, ending up in the company of story-telling friends. Although he will never make a speech in public, he is a brilliant raconteur in private, and his mimicry is inexhaustible. One after another he will roll out impersonations of famous conductors, fellow-composers and instrumentalists. His wit is dry. Whilst he considers ‘Elektra’ to be one of Strauss’s finest works, he admits to a real fondness for the sheep in Don Quixote ‘because their bleating sounds so anxious.’ Again he condemns the orchestration of Brahms’ first piano concerto as being ‘too full of beer and dumplings’ at the same time as delighting in the first subject of Schumann’s Second (corrected by Bax from the Fourth as Christopher originally wrote) which reminds him of ‘fleas skipping about in a circus!’

There are so many little snippets of fascinating information. I was interested to learn, for instance, that The Garden of Fand had been turned into a ballet called Picnic at Tintagel with choreography by Frederick Ashton and designs by Cecil Beaton. As Bax said, “It is really about Tristram and Iseult – all slightly bewildering! But it has been a terrific success in New York.” (It was premiered there in February 1952.) We also learn that the idea for the Scherzo of Bax’s Third Symphony – “…came to me at Morar (North West Scotland). I can even remember the exact place by the sea, opposite the islands of Rum and Eigg.” Another little facet that impressed me was Bax’s repeated request to Whelen to read and conduct the composer’s Overture, Elegy and Rondo which seems to run like a thread through this book; clearly Bax held this work in some regard. Whelen’s concert programme analysis is included.

What a shame that Whelen never completed his planned book on Bax (yet he helped Lewis Foreman considerably in the development of his biography). The world of music has clearly missed what promised, from the plan of Whelen’s projected book a more complete and fascinating study of the life and music of the dreamer that he championed.

Reviewed by

Colin Scott-Sutherland

The tantalising references to and quotations from the writings on Bax by the young conductor, Christopher Whelen, that appear in Lewis Foreman’s study, are now available in full in this curiously entitled book, published in an attractive format by the editor, Dennis Andrews who, from an intimate knowledge of his subject, provides a valuable introduction and numerous illuminating notes.

Christopher Whelen (1927-1993) studied music at New College Oxford where he developed an ambition to become a conductor. Unconventionally he canvassed for the opportunity and was fortunate in coming under the tutelage and influence of the then new conductor of the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, Rudolf Schwarz. In the event, as this beautifully produced book recounts, his predilection for things Celtic (and Yeats in particular) soon brought him into contact with the music of Bax, of whose work he was to become a life-long champion. He had earlier attended a live performance of Tintagel – and it must be remembered that, at the time, there were few enough opportunities to hear the music -the 1943 HMV discs of the 3rd Symphony under Barbirolli for long constituted the only Bax on record – yet with unerring accuracy and insight the young Whelen was drawn inexorably to the Seven Symphonies.

The course of this relationship, after a tentatively admiring letter in 1947, blossomed into a close friendship between the 22-year old conductor and the 66-year old composer. It will not escape notice that at 22, the young musician might be the envy of the aging Bax who, in ‘Farewell My Youth’, had written that age 22 was ‘the golden age in the count of a man’s years. I longed to be 22 and to remain at that age forever… What emerges most forcibly in this account of that friendship is the young conductor’s unerring instinct that the Symphonies were Bax’s most significant work. Throughout there emerges a personality – diffident enough on first meeting with Bax, but with a convincing certainty of his own view of the music. His conviction that Bax had a consummate mastery of formal design, all too often denied him by those who cannot see the wood for the episodic trees, comes over strongly: ‘Bax is a great musical architect. Nobody has yet pointed out the organic scheme behind each symphony. Critics talk of a ‘profusion of ideas’ failing to notice that each bar, each phrase stems from a ‘first idea’, as the American poet Wallace Stevens has called it. Once the scores have been cleaned up, on occasion re-marked, and then studied it will be seen that there are no such things as episodes or rhapsodizing. Everything is logical and surprisingly precise – Byzantine mosaics.’ It is regrettable that Whelen’s eventual performance of the 6th symphony was never committed to disc. – “I still dote on your performance of No 6 and want a repeat,” wrote Bax.

There are many interesting facets of Bax himself which emerge in the letters – the fact that he could say ‘I like the idea of No 6 being played at Bournemouth as it is a symphony of mine which I know least myself’ (my italics) and that he should comment on Whelen’s questionnaire about which suggested composers he most admired, ‘Leave out Delius – I was never wholly convinced by him’ is astonishing when one thinks of Eventyr and Song of the High Hills – and yet? The entire correspondence amounts to 39 letters. Brief but with valuable insights, 18 pages of photographs – with roughly half the book devoted to Whelen’s writings. It is somewhat ironic that Whelen’s ability to pursue his advocacy of Bax was curtailed when in 1952, with the necessity of earning a living, he became Musical Director of the Old Vic, which involved composing incidental music and such other duties. As he confessed in a letter to Lewis Foreman, ‘got myself swept into the theater and composition paradoxically much to Bax’s pleasure, though I don’t think he realised that by ’53 it would mean I would have to give up conducting more-or-less. I am not persuaded that any of the candidates have so far heard do the big works are in any way the right ones. ‘One is left with the feeling of regret that he was unable to complete the written study of Bax’s work which he not only loved but understood perhaps better than any of us.

© Colin Scott-Sutherland.

Reviewed by

Richard R. Adams

It has always seemed to me that Bax’s most ardent advocates have been those who perform music rather than those who are paid to write about it or schedule it on concert programs. In this regard Bax has been extremely successful in attracting musicians to his cause. This beautifully produced new publication highlights the efforts of one such musician who knew Bax at the end of his life and who did his utmost to keep Bax’s name before the public.

Christopher Whelen and Bax began their exchange of letters in 1949. At that time, Whelen was a 22-year old fledgling conductor who had successfully lobbied Rudolf Schwarz for a position as assistant conductor of the Bournemouth Municipal Orchestra. His interest in Bax began when he heard George Weldon conduct Tintagel. Dennis Andrews tells us that soon after that the young Whelen was buying every Bax score he could get his hands on but it was his discovery of the symphonies that convinced him of Bax’s greatness and also of his desperate need for a champion. He wrote of his admiration for Bax’s music to the great man himself and Bax replied with a very warm and appreciative note. Christopher next wrote about his intentions to conduct Tintagel and Bax again replied with suggestions and reminiscences about his life. These exchanges continued and the two men eventually met when Bax went to hear the young conductor perform his music.

It must have been very consoling for the aging composer to know of a younger musician who was taking up his cause. His greatest works had rarely been performed after the Second World War and Bax was well aware that he was persona-non-grata as far as the musical elite of the time was concerned. In his first letter to Whelen, Bax wrote “I am indeed delighted to hear of your enthusiasm for my work, for I don’t generally expect it to be much appreciated in this anti-romantic age!” Whelen scheduled as many Bax scores as he could during his years in Bournemouth including Tintagel, the Sixth Symphony, Garden of Fand, Summer Music and Overture, Elegy and Rondo. An astonishing and rather sad by-product of Whelen’s performance of the Sixth was the letter Bax wrote following the performance in which he states how difficult it was for him to remember his own themes due to the amount of time that had passed since he had last heard this masterpiece performed. This comment could only have motivated Whelen to do even more to encourage performances of Bax’s music for it wasn’t long before he began writing several perceptive essays on Bax’s music, many of which are contained within this volume.

Just before Bax died, Whelen became music director of the Old Vic Theatre Company, a position Bax supported. This career shift meant Whelen would have few opportunities to perform Bax’s music. His enthusiasm for the composer, however, never waned and he remained a tireless champion of the symphonies. He was in a unique position to write about Bax because he had studied many of the scores with the composer and he knew of Bax’s intentions. Andrews writes that Whelen had intended to write a book on Bax but that he had never found a successful structure in which to combine his reminiscences, his technical notes and his knowledge of Bax’s re-markings of the scores. The task ultimately fell onto Andrews, a life-long friend of Whelen, to compile the letters as well as Whelen’s own writings into one succinct book which can now be studied and enjoyed by all who wish to better understand this composer’s music.

Andrews contributes several chapters which help illuminate aspects of Whelen’s own complex personality and the reasons he was so attracted to Bax’s music (as well as the music of Roussel). He also offers his own vivid recollections of Bax and the almost fatherly way the composer responded toward the younger musician. It is a beautiful testament and one that challenges our understanding of Bax’s final years. It’s a well known that Bax hated growing old. His last great scores were written in the late 1930s after which he essentially retired. Bax is reported to have become more reliant on alcohol and some commentators have characterized him as a morose and bitter man, always complaining about his failing abilities and the growing neglect of his music. Bax’s writings to Whelen are completely devoid of self-pity or bear no trace of bitterness. On the contrary, Bax comes across as a contented and modest gentleman who, while expressing his displeasure at being under-performed, blames no one for his misfortunes (with the possible exception of a few music critics). There are no discourses on the horrors of growing old, just wonderful anecdotes about friends (“what a flame little Barbirolli is”) and women (whom he characterizes as ‘kittle-cattle.’ Bax would likely know!) Another trait that comes across is his extraordinary sincerity. Whelen wrote to Bax about a concert he was planning for the Radio Eireann Symphony Orchestra in 1951 in which he suggested doing one of his symphonies. Bax’s selfless advice was for the young conductor was to do something familiar so he could show the orchestra and public what he could do with something they knew.

This is a remarkable and beautifully produced book. It is the perfect companion to the brilliant studies produced by Colin Scott-Sutherland and Lewis Foreman. This book humanizes Bax in a way no other book has done for me and, most importantly, it documents the extraordinary efforts made on the behalf of a great composer by a much younger and devoted colleague. This new book now assumes a very prized place in my library.

© Richard R. Adams