Bax’s First Piano Sonata, in F sharp minor – Survey

Bax’s First Piano Sonata, in F sharp minor

A comparative review

by Christopher Webber

Discography (adapted from Graham Parlett)

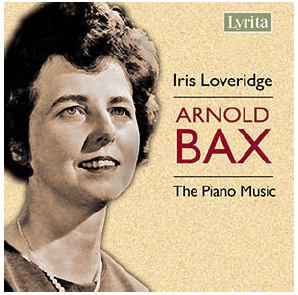

(1) Iris Loveridge. Lyrita LP: RCS 10 (m); Musical Heritage Society LP: MHS 7011 (m); CD: REAM 3113 (m). (2) Frank Merrick. Frank Merrick Society LP: FMS 7 (m). (3) James Roche. Sound News Productions LP (probably from the 1970s and not for sale).  (4) Joyce Hatto. Revolution LP: RCF 010; Concert Artist/Fidelio TC: FED-TC-011; Concert Artist CD: CACD 9011-2―announced in 2003 but not issued. (5) Eric Parkin. Chandos LP: ABRD 1206; TC: ABTD 1206; CD: CHAN 8496; CHAN 10132 (four-CD set); MHS CD: MHS 5479370 (four-CD set). (6) Marie-Catherine Girod. Opes 3D CD: 3D 8008; 3D Classics 122184. (7) Joseph Long. Privately recorded CD: WJL1 (‘Late Flowering of the Romantic Piano Sonata’, obtainable from Joseph Long, 25 Nethermains Road, Muchalls, Aberdeen AB39 3RN). (8) Ashley Wass. Naxos CD: 8.557439. (9) Michael Endres. Oehms CD: OC 565. (10) Malcolm Binns. British Music Society CD: BMS434CD. (11) Franziska Lee. Capriccio CD: C3010 (‘London Nights’).

(4) Joyce Hatto. Revolution LP: RCF 010; Concert Artist/Fidelio TC: FED-TC-011; Concert Artist CD: CACD 9011-2―announced in 2003 but not issued. (5) Eric Parkin. Chandos LP: ABRD 1206; TC: ABTD 1206; CD: CHAN 8496; CHAN 10132 (four-CD set); MHS CD: MHS 5479370 (four-CD set). (6) Marie-Catherine Girod. Opes 3D CD: 3D 8008; 3D Classics 122184. (7) Joseph Long. Privately recorded CD: WJL1 (‘Late Flowering of the Romantic Piano Sonata’, obtainable from Joseph Long, 25 Nethermains Road, Muchalls, Aberdeen AB39 3RN). (8) Ashley Wass. Naxos CD: 8.557439. (9) Michael Endres. Oehms CD: OC 565. (10) Malcolm Binns. British Music Society CD: BMS434CD. (11) Franziska Lee. Capriccio CD: C3010 (‘London Nights’).

Introduction: Biographical tone-poem, or abstract sonata?

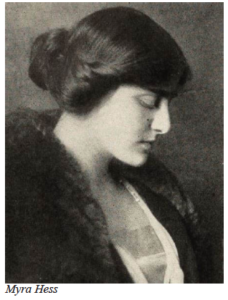

To use the tabloid defence against defamation claims, how far should the biographical content of Bax’s 1st Piano Sonata be a matter of public interest? The Queen reviewer following Myra Hess’s first performance of its original version in May 1911 had no doubt about the answer:

As a technical exercise one could wish for nothing more exacting than the ‘Romantic Tone-Poem’ … the composer presumably had some ‘programme’ in his mind when he wrote it, but since so clue was afforded of its meaning, the audience was left to imagine the romance that had inspired music so rhetorical as this proved to be.

At Hess’s suggestion, the ‘Romantic Tone-Poem’ was later renamed ‘Symphonic Fantasy’, perhaps to steer listeners away from such programmatic impertinence, and it reached its final published form in 1921, as plain ‘Sonata in F sharp minor’. So it might seem that Bax was distancing himself biographically from an important, purely musical statement.

Perhaps he might have agreed with one of the Sonata’s most brilliant exponents, Michael Endres, in conversation with Richard Adams at the time of his 2005 recording:

RA: The First Sonata in its original form was written in the summer of 1910 while Bax was in hot pursuit of a young Ukrainian beauty named Natalia Skarginska, whom he had met in England. He followed her back to the Ukraine where she suddenly announced her engagement to another man, Some commentators have said the First Sonata was written in reaction to Bax’s disillusionment over his failed affair as well as his enchantment with the Ukrainian people and landscapes. Do these extra-musical associations influence the way you prepare a work like the First Sonata?

ME: I don’t pay too much attention to biographical details as they do not explain the quality of a piece of music. It might provide some vague idea about what prompted the composer to write it but it doesn’t explain its artistic merit.

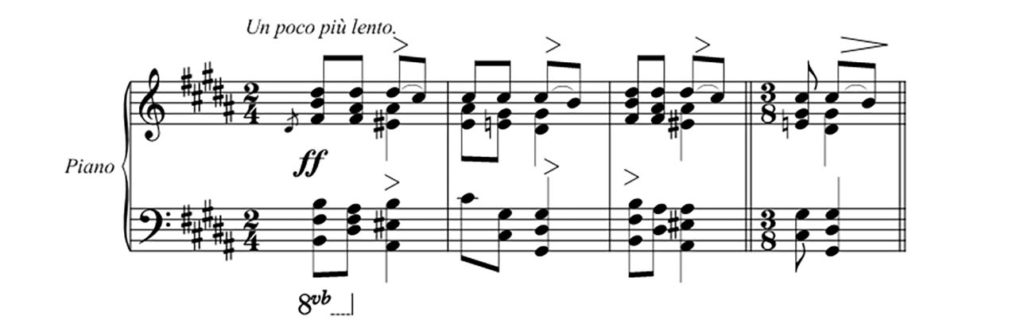

Bax indeed reveals a little about those promptings at the foot of the printed score (‘Written in Russia | Summer 1910 | Revised 1917-1921’); and its kinship with the contemporary Russian piano repertoire – not to mention its tintinnabulatory finale, probably added around 1919 – emphasises the strong sense of time and place. We can point to a more specific reference in Bax’s autobiographical Farewell My Youth. Describing his arrival in St. Petersburg on Easter Eve of 1910, while in pursuit of Skarginska (p.67), he describes how ‘Bells thundered and jangled from every church’, and his evocation of that moment in the Sonata is thunderous indeed, the notation expanding from two to four staves in an attempt to capture its dizzy intricacy.

Bax indeed reveals a little about those promptings at the foot of the printed score (‘Written in Russia | Summer 1910 | Revised 1917-1921’); and its kinship with the contemporary Russian piano repertoire – not to mention its tintinnabulatory finale, probably added around 1919 – emphasises the strong sense of time and place. We can point to a more specific reference in Bax’s autobiographical Farewell My Youth. Describing his arrival in St. Petersburg on Easter Eve of 1910, while in pursuit of Skarginska (p.67), he describes how ‘Bells thundered and jangled from every church’, and his evocation of that moment in the Sonata is thunderous indeed, the notation expanding from two to four staves in an attempt to capture its dizzy intricacy.

There is nothing picture-postcard about the work, and Endres is quite right about the irrelevance of ‘biographical details’ when it comes to the forensic process of preparing and communicating a one-movement work of such complexity. Yet for the listener it is different. The romantic movement, of which this Sonata is a very late flowering, puts the artist and their experience at the heart of the matter; so the autobiographical element hinted at by the composer is like a Pandora’s box – once opened, you cannot close it again.

None of this should be taken to imply that Bax’s First Piano Sonata is a self-indulgent stream of consciousness. It neither rambles nor meanders, developing seamlessly from a series of memorably-defined ideas; and every note counts – or must do, if the performance is to hold together. The same is true of its dark-toned, brooding yet highly idiomatic technique. This is no orchestral wolf in solo sheep’s clothing, and the spirit of the Sonata lies in its Lisztian play of pianistic timbres as much as its thematic or harmonic particularity. Recording quality matters here.

We have learnt from Vernon Handley’s accounts of this composer’s symphonies, that the prime duty of a Bax interpreter must be to clarify the complex but robust orchestral structures built by his fantastic imagination. Clarity is every bit as necessary in the instrumental works – especially in this one-movement Sonata, which with the sole exception of its monolithic successor and blood brother, the Second Piano Sonata, was to remain the longest single span he ever attempted. Its brooding array of moods, from fiery bravura and purple passion to delicate poetry and exhausted languor, culminating in that bell-jangling finale, require firm control as well as a supreme piano technique.

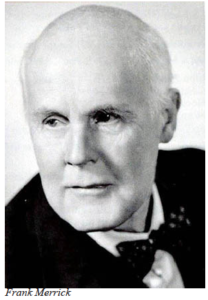

Analysis

Supreme technique is one thing we can take (pretty much) for granted, in the ten commercial recordings of the First Piano Sonata appearing between 1959 and 2022. These extend from Iris Loveridge’s pioneering LP account for Lyrita, to Franziska Lee’s recent Capriccio CD, reviewed here. We’ll find an eleventh recording listed in Graham Parlett’s indispensable discography, but this privately-pressed 1970s LP by the Irish pianist James Roche has never been publically available and is not discussed here. Nor do we have recordings from the Sonata’s first interpreter Myra Hess or Bax’s muse Harriet Cohen, though we do have an account (from late in his life) by the pianist and composer Frank Merrick, whose authentically romantic interpretation Bax had certainly admired.

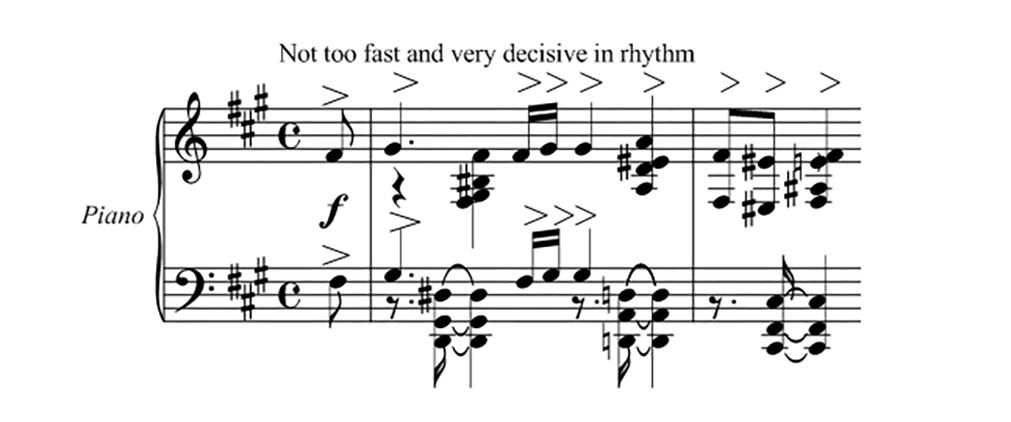

Although everyone plunges into Bax’s firm opening statement (p.1 of the Murdoch/Chappell edition) with gusto, there are a wide variety of speeds on offer. His equivocal instruction, ‘Not too fast and very decisive in rhythm’, allows interpreters plenty of leeway, although he defines something more specific, with the first return (p.13) of the theme, ‘tempo primo (allegro deciso)’. Many players start at a comfortable andante: Lee follows Bax’s markings precisely and expressively at this conservative pace, while Binns plays the third bar quavers staccato, rather than decisively as marked. Girod is slower than either: even in this most rhetorical of openings, her emphasis is on inner poetry rather than outward rhetoric. At the opposite extreme is Endres, whose hectic opening, thrown off with virtuosic aplomb, certainly takes Bax’s allegro deciso at face value. The feeling here is consciously theatrical, even if we might be excused for suspecting that the pianist had a train to catch: Endres is a firm believer in Handley’s doctrine of not loitering to smell individual flowers in the Baxian garden.

Hatto is romantically wild and impetuous, cavalier as to rhythm – her triplets are a very personal matter indeed – but unquestionably exciting. Merrick, ever the mahogany-panelled, 19th century-style romantic virtuoso, sounds sluggish in comparison, not helped by a tinny recording. An exaggerated rubato and firmata on the third note of the triplets in bar 4 holds up the music’s momentum, though emphasising its Lisztian rhetoric. Parkin suffers from a distant (if clear) Chandos recording, which perhaps accounts for the mezzo-forte rather than forte feeling of his first flourish. Like too much of his performance, this opening sounds oddly provisional.

Of the others, we can immediately warm to Loveridge’s spirit, her judicious use of the pedal producing an expansive, generous sound even through Lyrita’s rather thin, dim recording. Wass shares that richness, adding more pedal and his trademark heavy bass – though he almost double-dots the semiquavers, suggesting passing notes rather than the stoic emphasis Bax requires. At the opposite end of the spectrum is Long, who rations his pedalling to a minimum throughout, producing the dryer sound he prefers. Though often revealing, it’s not always totally convincing: in his review of his disc for MusicWeb, Colin Scott-Sutherland wrote that the result “doesn’t sound like Bax. Balfour Gardiner once remarked ‘Oh there’s old Arnold improvising away with the pedal down all the time’…”. Perceptively, he goes on to point out that although no pedal markings appear in the scores, directions such as smorzando, brazen and glittering and thick and heavy indicate that Bax expected resonant use of it throughout his piano sonatas.

Of the others, we can immediately warm to Loveridge’s spirit, her judicious use of the pedal producing an expansive, generous sound even through Lyrita’s rather thin, dim recording. Wass shares that richness, adding more pedal and his trademark heavy bass – though he almost double-dots the semiquavers, suggesting passing notes rather than the stoic emphasis Bax requires. At the opposite end of the spectrum is Long, who rations his pedalling to a minimum throughout, producing the dryer sound he prefers. Though often revealing, it’s not always totally convincing: in his review of his disc for MusicWeb, Colin Scott-Sutherland wrote that the result “doesn’t sound like Bax. Balfour Gardiner once remarked ‘Oh there’s old Arnold improvising away with the pedal down all the time’…”. Perceptively, he goes on to point out that although no pedal markings appear in the scores, directions such as smorzando, brazen and glittering and thick and heavy indicate that Bax expected resonant use of it throughout his piano sonatas.

I’ve said something about how all ten players tackle Bax’s opening, because each of them immediately lays their cards on the table. Interpretation of the First Sonata lies broadly between two poles. At one extreme we have the old-school, rhetorical romantics, such as

Merrick and Hatto, while Girod’s and Lee’s more reflective accounts are at the other. As to pace, Endres’s impetuosity could not be further removed from the considered weight of Wass, who takes nearly five minutes more over the work. Like other great piano sonatas, Bax’s First proves to be a fascinatingly broad church.

This sospirando (‘sighing’) theme, introduced immediately after the opening paragraph  (p.5), produces a wide spectrum of approaches. Endres’s delicate, Lisztian phrasing is a connoisseur’s delight, while in extending the first note and cutting the dying fall short, Hatto’s lamentation is exaggeratedly operatic. There’s a spellbound clarity to Lee’s classical restraint, while Loveridge – as elsewhere – has a tendency to truncate the last note of each phrase, articulating them at the risk of short-windedness. Wass puts the brakes on firmly here, producing a graphic sense of resignation in the face of loss, perhaps at the expense of momentum.

(p.5), produces a wide spectrum of approaches. Endres’s delicate, Lisztian phrasing is a connoisseur’s delight, while in extending the first note and cutting the dying fall short, Hatto’s lamentation is exaggeratedly operatic. There’s a spellbound clarity to Lee’s classical restraint, while Loveridge – as elsewhere – has a tendency to truncate the last note of each phrase, articulating them at the risk of short-windedness. Wass puts the brakes on firmly here, producing a graphic sense of resignation in the face of loss, perhaps at the expense of momentum.

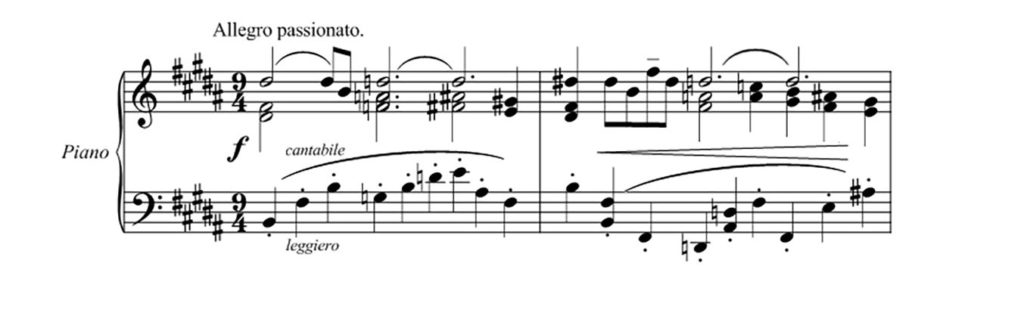

In a sonata form movement, this Russian-sounding allegro passionato outpouring (p.6)

might function as the true second subject; and there’s no doubt that its heart-on-sleeve, amorous sensuality comes as a fluent contrast to the taut tension of the opening pages. But it is important not to linger over it too much: Loveridge evokes a soothing, cradling berceuse, and Lee likewise keeps the emotions on a tight rein. Girod sticks to her concept of musing poetry, perhaps at the expense of flow. Endres glides around this exotic flower with sweeping mastery, while Merrick produces a staggering moment of rapt, nocturnal fantasy. Whatever its shortcomings as to piano sound or interpretative caprice, in moments such as this his performance reveals Bax’s musical heart like no other. Wass sounds over-careful in comparison, Long is emotionally subdued, though scrupulously following the composer’s roller-coaster piano and forte directions.

This uncomplicated theme (p.11) appears to sum up the preceding paragraphs, almost as if Bax was saying “that’s how I feel about it, take it or leave it”. It’s therefore important to register its simplicity, as a corrective to the plethora of shifting (even bitonal) chromaticism which precedes it. Binns understands this function well, marking it calmly and cleanly, with a refreshing sense of wiping the slate clean. Lee and Long, both forceful and very strictly in time, refresh the music by their clarity, while Wass offers a simpler moment of repose.

It’s odd to find Endres in the same boat as Hatto, but both charge into the theme, without much sense of lento or Bax’s required relaxation in tempo – Parkin even takes più lento as an invitation to play faster! He is not alone: Girod goes startlingly out on a limb, suddenly turning on the spirit of a French 2/4 rigaudon in her light and witty delivery of the phrase, a gambit she repeats on its reappearance much later in the work. She certainly makes us sit up. Once again Merrick is class of the field at this crucial juncture, producing a fevered sense of nightmare through the bitonal crescendo, before releasing the music into conscious, relieved content. It’s a moving moment.

It’s odd to find Endres in the same boat as Hatto, but both charge into the theme, without much sense of lento or Bax’s required relaxation in tempo – Parkin even takes più lento as an invitation to play faster! He is not alone: Girod goes startlingly out on a limb, suddenly turning on the spirit of a French 2/4 rigaudon in her light and witty delivery of the phrase, a gambit she repeats on its reappearance much later in the work. She certainly makes us sit up. Once again Merrick is class of the field at this crucial juncture, producing a fevered sense of nightmare through the bitonal crescendo, before releasing the music into conscious, relieved content. It’s a moving moment.

Shortly afterwards (p.12), Bax offers us the allegro passionato theme recast as a darkly sardonic funeral march, perhaps suggesting the attempted burial of love. Many of these pianists make hay here. Girod is glintingly light and bright, while Lee’s clear and sombre rhythms make sure every note counts. Long gives us point-blank, deadpan irony, close cousin to Loveridge’s flaunting, upbeat goosestep. Endres is faster still, icily detached as he skates eerily over the surface. If Merrick suggests an almost Mahlerian edge, Hatto’s Hammer-horror Russian funeral is perhaps several heavy steps too far.

I suppose that sonata-movement mavens would hear this funeral march as initiating the work’s development, but Bax’s process is organic, more a parade of variations on the work’s four themes than a development proper. At one point we seem to be on the waters: the extended ostinato section (from p.18) has something of Liszt’s Lugubrious Gondola about it, which Wass seems to acknowledge, with a bass-heavy sense of dark currents slowly circling under the surface. Merrick sounds a mite impatient in his evocation of scudding wavelets, and although Endres keeps it moving just as fast, he adds a furious accuracy which impresses us – as so often – through breathtaking virtuosity and command of the overall structure, even at the expense of detail.

Swiftly we reach Bax’s broad and triumphant homecoming, with its festive bells (p.27); and although nobody falls short here, some succeed better than others at investing the finale with the proper panoply of clangourous colour. Though Loveridge has held something in reserve for her very impressive arrival, her bells sound more muffled than ideal, losing definition in the mono recording. Parkin sounds distanced emotionally as much as physically, conveying (as elsewhere) little involvement; and although Binns is nobly proud in the theme, his bells sound a touch Anglican rather than Orthodox. Long’s close-miked restatement of the theme doesn’t have such a strong sense of homecoming, but his unexpectedly lavish pedalling for the bells brings a spacious breath of cool air. Wass is certainly broad, very slow and solemn, his idea of triumphant grandiose in the extreme.

Swiftly we reach Bax’s broad and triumphant homecoming, with its festive bells (p.27); and although nobody falls short here, some succeed better than others at investing the finale with the proper panoply of clangourous colour. Though Loveridge has held something in reserve for her very impressive arrival, her bells sound more muffled than ideal, losing definition in the mono recording. Parkin sounds distanced emotionally as much as physically, conveying (as elsewhere) little involvement; and although Binns is nobly proud in the theme, his bells sound a touch Anglican rather than Orthodox. Long’s close-miked restatement of the theme doesn’t have such a strong sense of homecoming, but his unexpectedly lavish pedalling for the bells brings a spacious breath of cool air. Wass is certainly broad, very slow and solemn, his idea of triumphant grandiose in the extreme.

Endres takes everything firmly in his stride, strictly in tempo now that the end is in sight. He’s at the opposite extreme from Girod, whose enchanted haze of bells is an end in itself. Hatto, thunderous in the theme, pounds out rowdy bells which jangle splendidly, albeit in capriciously personal tempi. Lee allows the theme to emerge subdued by experience, more bloodied-but-unbowed than triumphant; and though her bells are on the tinkling side, everything emerges from Capriccio’s recording with matchless clarity. Merrick’s stamina may be waning by this stage, but – not surprisingly – his bells swing and chime magnificently.

The recordings summarised

(1) Iris Loveridge (18:43)

Despite Lyrita’s soft and grainy recording, Loveridge’s warmly intelligent performance belies its years. Her habit of rounding off phrases with sudden sforzandi can be disconcerting once you notice it, but as an established benchmark, this balanced reading remains well worth hearing. Though passages requiring brilliant articulation don’t come off so well, and we can’t hear much pedalled bass in the ringing finale, the sonata’s poetry and rhetoric emerge strongly through the aural mists.

(2) Frank Merrick (19:16)

Despite the caveats – lax rhythmic consistency and fast-and-loose attention to Bax’s dynamic and tempo directions – this authentic ‘period’ performance brings us closest to the composer’s own world. The sense is of improvisation in the moment, and in several passages Merrick conjures a transcendental magic, not least in his majestic, bell-haunted finale. It is very much a ‘creator’s vision’ of the sonata, from an earlier 20th century tradition.

(4) Joyce Hatto (20:11)

In case there’s any doubt, let’s be clear that this is the real Joyce Hatto! Her approach is old-school, similar in many ways to Merrick’s, but without his structural mastery and imaginative insights. Cavalier as to note values and capricious as to tempo, Hatto offers a roller-coaster of romantic colour and barnstorming theatricality which is nothing if not vividly alive. It’s very communicative, if ultimately leaving an impression of show rather than substance.

(5) Eric Parkin (19:34)

Distantly recorded, in Chandos’s clear but over-reverberant sound, Parkin’s performance fails to ignite. So generalised are the dynamics and sense of character, that the recording runs the risk of conveying a sense of routine, rather than consistently deep engagement with Bax’s poetry and passion. Some of the pianism might even be described as lumpy. For many years this was the most widely-available recording, but it is now firmly superseded.

(6) Marie-Catherine Girod (20:17)

Girod’s naturally-recorded reading is from the first intégrale of Bax’s sonatas by a European pianist, but its interest is more than historical. Many phrases substitute impressionistic sforzando accents for Lisztian bravura, and her treatment of Bax’s passionato elements often has a delicate, Chopinesque poetry. Despite some questionable interpretative decisions along the road, this superb pianist always knows what she wants and how to achieve it. Girod’s is the earliest of the ‘poetic’ as opposed to ‘epic’ readings.

(7) Joseph Long (21:35)

Despite some reservations about Long’s undernourished sound and forensic approach, this remains an absorbingly intelligent traversal of the score. Questions of pedal style apart, it’s worth noting that he observes the composer’s plethora of dynamics with unusual fidelity, for instance playing the allegro passionato ‘second subject’ in a subdued way, precisely as Bax marks. With its real care for voicing of registers, this classical reading consciously underplays the score’s emotive Lisztian and Russian elements.

(8) Ashley Wass (22:28)

With his preference for bass-rich sound, excellently captured by Naxos, and for unhurried tempi – this is the slowest version on disc – Wass’s reading is very effective, in the traditional mould. He follows Bax’s dynamics, employs nuanced rubato and gauges his pedalling well. Though he is apt to linger, occasionally brooding on detail at the expense of the whole (with a resulting loss of momentum), this is one of his best Bax recordings and remains a strong recommendation.

(9) Michael Endres (17:51)

Once we’ve recovered from his perilously fast, almost brusque opening gambit, Endres’s urgency develops a compelling sense of momentum. Other pianists may illuminate detail more lovingly, but he never loses a sense of where the sonata is going, and his matchless virtuosity encompasses breathtaking, crystalline delicacy as well as force. This swift reading – the fastest on record – ultimately succeeds in clarifying the musical narrative with an iron consistency which no other recording attains.

(10) Malcolm Binns (19:25)

One of the most accomplished 20th century British pianists, Binns recorded his complete traversal of Bax’s sonatas late in his career – a much earlier single LP of the Second Sonata remains a collector’s item. His reading of the First calls on a wealth of experience, within a tradition stretching back to Hess and Cohen. There may be more compelling visions, but Binns has an easy, natural sense of how to balance the work’s rhetorical and poetic components, and the BMS recording matches his solid interpretative strength.

(11) Franziska Lee (21:16)

A Korean pianist resident in Germany, Lee’s Capriccio recording is class of the field from the technical perspective, offering outstanding clarity in every register, and a naturally expansive ambience. Nor does her artistry let the side down. Although there are more muscular, bravura readings available, her poetic precision and easy articulacy are superb. Everything counts, everything ‘sounds’, revealing new facets to the music. One or two fussy moments (for instance, p.14’s cantabile e semplice) are outweighed by Lee’s consistent sense of rightness.

Recommendations

Nearly all these ten performances have something special to say about Bax’s First Piano Sonata. In particular, everyone interested in the composer’s inner world should try to hear Frank Merrick on Nimbus, though this can hardly be a ‘library recommendation’ by reason of its pianistic frailties. Ashley Wass’s dark-hued reading for Naxos certainly fits the ‘library’ bill, but in the end two performances at opposite ends of the spectrum are even more compelling. Franziska Lee (Capriccio) clarifies every gesture, in a poetic account supported by an outstanding recording; but in the last analysis, Michael Endres’s breakneck, dramatic traversal dares more and achieves most, placing Bax’s amorously-inspired masterwork in the pantheon of the great piano sonatas, where it belongs.

Nearly all these ten performances have something special to say about Bax’s First Piano Sonata. In particular, everyone interested in the composer’s inner world should try to hear Frank Merrick on Nimbus, though this can hardly be a ‘library recommendation’ by reason of its pianistic frailties. Ashley Wass’s dark-hued reading for Naxos certainly fits the ‘library’ bill, but in the end two performances at opposite ends of the spectrum are even more compelling. Franziska Lee (Capriccio) clarifies every gesture, in a poetic account supported by an outstanding recording; but in the last analysis, Michael Endres’s breakneck, dramatic traversal dares more and achieves most, placing Bax’s amorously-inspired masterwork in the pantheon of the great piano sonatas, where it belongs.

© Christopher Webber, 2022