BAX SYMPHONIC VARIATIONS (REISSUES) Reviewed by Christopher Webber

BAX SYMPHONIC VARIATIONS (REISSUES)

Reviewed by Christopher Webber

THE SIR ARNOLD BAX WEB SITE

Last Modified 10th October 2004

Arnold Bax: Orchestral Works Vol.7

Arnold Bax: Orchestral Works Vol.7

Margaret Fingerhut (piano)

London Philharmonic Orchestra

Bryden Thomson (conductor)

Symphonic Variations,

Winter Legends

Chandos Classics CHAN 10209 (2-CD) (93:07)

[rec. All Saints’ Church Tooting 1986-7]

Arnold Bax

Arnold Bax

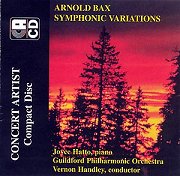

Joyce Hatto (piano)

Guildford Philharmonic Orchestra

Vernon Handley (conductor)

Symphonic Variations

Concert Artist CACD 9021-2 (45:52)

[rec. EMI Abbey Road Studios 1970]

Perhaps more ink has been spilt over the Symphonic Variations than any other Bax work. Is this, his longest orchestral piece, a concerto or not? Is it a genuine set of variations? What is the significance of the sectional titles? Do these and the musical self-quotations point to a hidden, autobiographical key? That these questions arise at all signposts a fundamental problem: is the Symphonic Variations a masterpiece, or inflated self-indulgence?

Perhaps the sanest comment, oddly enough, came from the provocative Kaikhosru Sorabji, who claimed that “… it occasionally reaches a pitch of fantastic and imaginative beauty that Bax touches nowhere else, except in The Garden of Fand.” And rarely touched by others, one might add—except in a handful of Russian works, notably those by Rachmaninov which clearly informed Bax’s taste at this watershed of his composing life. For the Variationsproved the gateway through which he moved away from the symphonic poem towards the abstract, large-scale forms of symphony and concerto which were to preoccupy him over the next twenty years.

Listening once again to these two recently remastered and reissued recordings, I’m still in two minds. There’s something unbalanced, even feverish about the Symphonic Variations. Few musical works brood so intensively over so little material, and its moments of vision emerge out of an almost obsessive uniformity of mood which can make it as exhausting an experience for the listener as for the soloist, scarcely rested during the work’s fifty minutes’ course. The matter, of course, is romantic love—or, depending on the armour-plating of your sympathies, sexual infatuation. Reflexive, subjective and personal, it is at the very least a remarkably public declaration of a private passion.

For the Symphonic Variations are rooted in the composer’s feeling for its only begetter and first soloist Harriet Cohen, firmly established by 1920 as Bax’s muse, mistress, bliss and bane. She has been blamed for encouraging Bax to butcher the work after its premiere under Sir Henry Wood, and for a determination to treat the cut product as her personal fiefdom. Joyce Hatto’s reminiscence of a coffee-house meeting with Bax and Cohen back in 1943, included with her performance on Concert Artist, is a vivid testimony to Harriet’s grip over performing rights, and there’s no doubt that she was responsible for the work’s absence from the concert platform after World War II, when she could no longer physically play it. But who would have willingly put such a love-token out for hire?

It’s been said that the mutilations inflicted on the Symphonic Variations after its premiere were down to Harriet’s inability to manage the demanding solo part. However, judging from contemporary accounts it’s clear that her playing was crucial to the work’s initial success; and according to Colin Scott-Sutherland the cuts were instigated by Wood, who felt the piece would play better shorn of Variation I (“Youth”) and otherwise trimmed. Once Harriet had the revision under her fingers, she perhaps understandably stuck with it. Curious evidence of that bad, old truncated score can be heard in Joyce Hatto’s recording, where a single, loud orchestral chord—sole relic of the reworked transition after that major cut—disturbs the contemplative piano solo at the start of Variation II (“Nocturne”.) Margaret Fingerhut’s version corrects this and numerous other textual errors.

Which brings us, finally, to the two recordings. Neither is ideal, but between them they make out a good case for Bax’s most ambitious concertante work. Fingerhut’s, originally issued on LP and CD in 1987, is warm, beautifully prepared and impeccably executed. Conductor Bryden Thomson eschews drama in favour of lyric rumination, and though the results can be of transcendent delicacy, the performance is not without its longeurs. Then there’s the sound. The Chandos LP, rich, detailed and ample in dynamic range, was of demonstration quality. The CD was monochrome, congested and seriously horrid. Fortunately, the new mastering is a huge improvement, the strings and piano are sweet, the balance realistic, the lugubrious mush of individual woodwind lines banished to a bad memory.

The piano itself is more soloistically forward than Fingerhut’s sensitive but self-effacing playing suggests—she and Thomson work in concertante rather than concerto mode throughout. Contrariwise, though Joyce Hatto is more discreetly placed within the body of orchestral sound, she rides the piece as a 19th century, bravura warhorse. Her 1970 recording marked the end of a personal crusade to perform the work which had lasted twenty years, and that shows. There’s much more colour and excitement here. Everything’s leaner and faster—indeed once or twice the pianist’s headstrong enthusiasm threatens to detach her from her conductor and his Guildford players, who consequently find themselves playing devil-take-the-hindmost rather than Bax. Concert Artist’s orchestral sound comes up pretty well in the new transfer, brighter and drier than Chandos’s churchy acoustic, constricted at the not infrequent climaxes but a quantum leap away from the thin, acidulated distortions of the old Revolution LP pressing.

Hatto’s urgent advocacy in the more vigorous variations “Strife” and “Play” makes her the preferred choice for newcomers to the Symphonic Variations; and structurally it makes better sense. She and Handley find greater light and shade than their rivals throughout, and her technical grasp of the prevailing reveries is always impressive, often tender. I only wish the same could be said of the actual sound of her instrument, which comes over as tinny, muffled and anything but well tempered. This is a real drawback, and Bax’s moments of proto-Szymanowkian sensuality—notably in the transcendental intermezzo “Enchantment”—are more exquisitely sustained by Fingerhut.

Chandos have recoupled her performance with Bax’s later, equally substantial piano concertante Winter Legends, on two CDs for the (mid)price of one. That performance has many of the same pros and cons, and disappointingly the equally reverberant All Saints’ Tooting recording has not been remastered to anything like equal effect—Fingerhut’s Winter Legends is a serviceable reading for want of a better. Concert Artist offer no filler and short measure, though Hatto’s touching memoir helps justify the full-price. The liner notes mirror the inherent contrast between the two recordings, with Burnett James offering a clearer, more succinct roadmap for the older recording and Lewis Foreman a wider-ranging, more discursive essay for Chandos.

Neither performance fully answers the questions of form and content inherent to these Symphonic Variations, but Hatto’s focussed energy and Fingerhut’s subtlety between them reveal many of Bax’s possibilities. There’s room for an outstanding modern version (Ashley Wass and Naxos?) to fuse their insights and get closer to squaring the magic circle; but meanwhile it’s good to welcome both these recordings back where they belong—and for the first time in CD sound which does them justice.

© Christopher Webber 2004