Bax at Morar by Christopher and Sheila Webber

Bax at Morar

by Christopher and Sheila Webber

THE SIR ARNOLD BAX WEB SITE

Last Modified January 26, 2002

Outside the Morar Hotel (All photos by Sheila Webber)

Many Baxians know well enough that the composer spent most winters between 1928 and 1939 at the Station Hotel, Morar, on the rugged North-west coast of Scotland. We know that from 1930 he stayed with Mary Gleaves. Thanks to Ian Lace’s lucid guide and photographs we also know something of Morar’s geography. But what drew Bax back year after year? Was it the scenery? Was it the hotel? Was it even, unlikely though it might seem for Northern Scotland, the climate?

We have the evidence of the music he set down during those years – a small matter of five major symphonies, two concertos, and a bevy of orchestral and chamber works including the evocative 4th Piano Sonata. Then, there were the obvious practical reasons. By the late 1920’s Bax’s music no longer flowed in an endless torrent, inspiration had to be encouraged and nurtured. Distant Morar gave him time and space to focus on the recomposition and scoring of his major works, far removed from the social and professional demands of London – not to mention Harriet Cohen. But why Morar?

Armed with Ian Lace’s article, quantities of sensible raingear, and a CD of the 4th Symphony (Chandos, Thomson) my wife Sheila and I sallied North to spend four days and nights in what is now the Morar Hotel, at the turn of the year when the dank and midge-infested Highland Summer finally yields to the drier days and fiercer drama of “Red Autumn”.

It turned out to be a time of human drama, too, what with the Great Petrol Crisis and all. Unlike Bax we came from the North, from Plockton and the seals. Like him, though, we reached Morar by public transport, by way of train to Kyle, bus across the new Skye bridge down to Armadale, and ferry to Mallaig – though we cheated by taking Mrs MacDonald’s taxi for the last leg to the Hotel. No petrol shortages here, and no motoring tourists. A big boatie had crept out of Grangemouth just before the blockade and was keeping the Highlands and Islands well-stocked, but drivers from Glasgow and beyond didn’t know about that. Traffic was local and limited, which only added to the sweet peace and quiet of the place.

Morar Sands

The Hotel is the last staging post on the Road to the Isles, prettily perched on a hillside overlooking the Atlantic. The Road is quiet now, and as you walk down to path to the beach you realise why. A tastefully sunken bypass has cut a swathe through the rocks, the birches and blackberry bushes, so nowadays you should look right and left before racing across the tarmac and down to the silver sands to search the rock pools and watch the wheeling gulls and curlews.

Lesson One. In spite of Bax’s own carefully fostered romantic legend about the place (to put off casual callers?) Morar was never really that remote, or that lonely. The rail station is ten yards from the Hotel, and there were comfortable sleeper trains direct from London to Mallaig, so Bax didn’t even need to change at Glasgow. According to Patrick Hadley his Morar days were spent ” … sometimes in polar conditions, in a dingy unheated room, working in an overcoat …” In truth, hotel rooms would have been dingy and unheated anywhere outside central London, and the polar conditions are a romantic fantasy. The truth of the matter is that this coast enjoys a uniquely equable climate, thanks to the warm waters of the Gulf Stream which makes landfall in this precise spot – there are palm-trees in Plockton, a few miles to the north. Even in the depths of winter, Bax would have rarely found snow or intense cold on this Morar seaboard (his own well-known snowscape snap was, significantly enough, taken inland). Morar is civilised.

Civilised, but not snobbish or sophisticated. From outside the Hotel, as Ian Lace noted, is surprisingly reminiscent of Bax’s last home, the White Horse at Storrington. The likeness persists indoors. The Morar Hotel was never one of those highland haunts for American millionaires wanting to ape the aristocracy or stalk the Egon Ronay Scottish Experience. It was then as it is now – warm and friendly, an unpretentious and affordable station hotel offering straightforward food and service with a genuine smile. The choice for dinner includes local smoked salmon and haddock, stuffed roast chicken, and Pear Condi (recommended), all great favourites with the coach parties that are the Hotel’s summer stock in trade. This is a place where anyone can feel at home.

The dining room boasts one of the best views in Scotland, though this isn’t the room where Bax would have eaten. Since 1953 and the coming of the front extension, the old dining room has formed part of the open-plan lounge/lobby which also houses the all-important bar. The stuffed animals are doubtless of pre-war vintage, though of course they’ve been shuffled into a murky corner of the lounge above the coffee https://levivard.com range. Most important, as at Storrington it’s an easy journey from the best bedrooms on the first floor, down the staircase and into the cosy resident’s bar, now moved a few feet from Bax’s time onto the site of what used to be the kitchen.

Curiously, Bax’s room – No.9 on the far right front of the first floor – continued to enjoy it’s spectacular sight of sand, land and sea until a year or two ago, when the latest extension-to-the-extension finally blocked off the lot. What a view it had been! Our room was on the new frontage, a few feet forward of Bax’s, and with an outlook as unencumbered as his would have been in 1939. In the foreground the estuary with its rocks and transient pools, eternal battleground between white sand, cold highland river and warm ocean tide. And in the far mid-distance, naturally framed between two rolling headlands, the cloud-capped mountains of the Island of Rhum.

Lesson Two. Rhum surely lay at the heart of Bax’s enchantment with Morar: “I am having a lovely quiet time here on the edge of the Atlantic (and with some of the Hebrides over the sea),” he wrote to Tilly Fleischmann in November 1932, and from his room he would indeed have glimpsed the steep crags of Eigg nosing over the Southern headland, and the Point of Sleat on Skye to the North; but in this part of the world it is impossible not to be drawn and held by the magic Island of Rhum. Shapeshifter Rhum never holds one mood for more than ten minutes at a time, seems never untouched by cloud, moves seamlessly between distant bleakness beyond baleful, grey-rolling seas and near-southern, smiling blue calm. That is, when it’s visible at all through the rain (see photos).

Atlantic with Rhum

One memorable night, around midnight under a Harvest Moon at low tide, we gazed in wonderment at an uncanny symphony of deep blues, sky inseparable from sea, linked by wispy filigrees of grey mist; and hovering above all, the peaks of the distant Island, revealed in their glory, seemingly so close you could almost reach out and touch them. Rhum and its moods make Morar what it is.

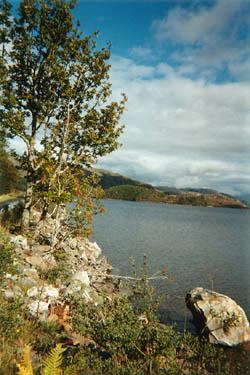

Or very nearly so. For there is another remarkable sight in store. Opposite the hotel and beyond the railway crossing lies a steep little hill, and on that hill there is a cross. Bax, despite his lack of a head for heights, must have climbed up here often – not for religious consolation, but because the view is so startling. To the west, the sea and Islands in all their shifting shades; to the east, he would have gazed along the entire length of Loch Morar, a wild Northern fastness some 30 miles long, bounded by the bleak, imposing and oppressive Grampian mountains. The Loch is one of the loneliest, and certainly the deepest freshwater lake in Europe, boasting its own monster to rival Nessie. (She’s called Morag, but alas declined to appear for our benefit).

Lesson Three. It is precisely the contrast, the unimaginable contrast between island-sea and mountain-loch that is so breathtaking. This must have spoken to Arnold Bax, himself regretfully turning away from the old, known and loved world of Celtic sea and Island celebrated in the 4th, towards the austere Northern landscapes of the 5th and later symphonies. Both are here at Morar, separated only by a turn of the head. That 4th Symphony with its direct reminiscence of the earlier piano “Romance” was a leave-taking in other ways, too, as Bax turned from Harriet to the gentler, more comforting love of Mary Gleaves. Morar, above all, was Mary’s place.

No wonder that even beyond Morar’s accessibility, its benign climate and the unstuffy congeniality of the Hotel, this place held such appeal for Arnold Bax. Turning one way, he could still cling to the romance of youth, the tantalising Celtic wonderland of the West, so close you could almost reach out and touch it. The other way lay the harsher, austere realities of the North, cold, impassive and age-old. Intensely troubled by the inevitability of his own physical decline, a sadder and probably no wiser man, Bax the “Brazen Romantic” still yearned to live his dream of youth. At Morar, with Mary, he could just manage it – with the Northern mountains ever at hand to remind him of the necessity to look forward as well as back.

Quite aside from its intrinsic natural glories, and the pleasant, relaxed company at the Hotel, we both felt that the stay in Morar had given us a subtler insight into the way the place itself, convergent point of Island-Sea and Mountain-Loch, mirrored and helped articulate the musical mind of a man who last walked on the selfsame sands over sixty years ago.

Eigg (left), Rhum and the Sound of Sleat on Skye (right)

from the Road to the Isles at Morar (Photo Sheila Webber)

Text and images © Sheila and Christopher Webber, 2000