Bax and Decca’s British Music Collection – Reviews by Graham Parlett and Christopher Webber

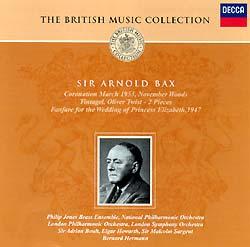

BAX: Fanfare for the Royal Wedding; Oliver Twist (excerpts); November Woods; Tintagel; Coronation March. Academy of St Martin-in-the-Fields, London Philharmonic Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, National Philharmonic Orchestra, Philip Jones Brass Ensemble. Sir Adrian Boult, Bernard Herrmann, Elgar Howarth, Sir Neville Marriner, Sir Malcolm Sargent. Decca CD: 473 080-2

THE SIR ARNOLD BAX WEB SITE

Last Modified July 20, 2002

Decca CD: 473 080-2

Review by Graham Parlett

This CD in Decca’s ‘British Music Collection’ contains every orchestral work by Bax that the company recorded between 1953 and 1996 – a total of 49 minutes, which just goes to show how much we owe to the efforts of Lyrita, Chandos and Naxos. It includes some of Bax’s finest works (Tintagel, November Woods) as well as some minor pieces from his later years and has brief but adequate notes, though not free from errors: Enchanted Summer is not for tenor, chorus and orchestra; and why does Elgar Howarth’s name appear on the front of the booklet and nowhere else, while Neville Marriner’s name is omitted?

The earliest recording here is Sargent’s performance of Bax’s penultimate work, the Coronation March, completed in November 1952 for the forthcoming coronation of Elizabeth II in June 1953. Bax can have had little enthusiasm for writing such a piece and he resorted to lifting the trio section straight out of his Victory March (1945), which itself was lifted from the film score for Malta, G.C. (1942). As he told May Harrison: ‘I am now engaged upon trying to write a Coronation March (funny without being vulgar!) for the Abbey Service. I think the result will be that my reputation will be killed for all time. However I am old now and it does not matter’. (‘…funny without being vulgar’ quotes W.S. Gilbert’s comment on Irving’s Hamlet.) Sargent makes the most of the score, and indeed Bax much preferred his performance to that of Boult, who conducted it at the ceremony itself. The recording was made on 29 April 1953, and the sound is remarkably good for its age.

Boult’s first recording of Tintagel is one of the finest to have been made of this score and is to be preferred to the later one he made for Lyrita, even though that had the advantage of being in stereo. The performance is splendid, and it is a pity that the sound on this 1954 mono recording is so poor. Boult did not have a high opinion of Bax’s music but he did admire Tintagel and this certainly comes across here. The faster middle section, with the sea becoming ever more turbulent, is exciting, and the wonderful moment towards the end where the Big Tune returns in triumph is perfectly paced.

Neville Marriner’s performance of November Woods is far less dramatic than those of Boult (Lyrita) and Lloyd-Jones (Naxos): the timpani strokes on p.25 of the score, for example, are barely audible here whereas in the Naxos recording they can be heard with startling clarity, and somehow the climaxes just do not come across as effectively. Nevertheless, the recording is otherwise exceptionally clear, and the frequent harp arpeggios and glissandos and woodwind figurations can be heard to greater effect than in the other recordings. The slow middle section is wonderfully luminous, and there is much to be said for Marriner’s thoughtful approach to the score. It may not be as overwhelming as some performances, but it contains some beautiful moments.

Bernard Herrmann’s recording of ‘Fagin’s Romp’ and the finale from Oliver Twist was made at the beginning of November 1975, less than two months before his death, and I remember slipping into Kingsway Hall and slouching in the stalls at the recording session praying desperately not to be noticed by a very grumpy Herrmann as he presided over an increasingly sullen NPO; at one point I thought he was going to come to blows with the timpanist, whom he accused of coming in at the wrong place, a charge strenuously denied. (Incidentally, and quite irrelevantly, I last saw Herrmann in a small London record shop exactly a week before his death, which took place on Christmas Eve in Hollywood; he was with Charles Gerhardt and was buying, I remember, a recording of Franck’s Psyché.) Herrmann’s performances, it must be said, are leaden: the humour of ‘Fagin’s Romp’ is entirely lacking, and the finale is taken so slowly that at one point the music nearly grinds to a halt.

Finally (or, since it opens the CD, perhaps I should say ‘firstly’) we have the second of Bax’s fanfares written for the wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Philip Mountbatten in November 1947, its concluding bars obviously designed to lead straight into Mendelssohn’s Wedding March. The slower middle section’s typically Baxian harmonies sound well enough, but the tempo for the opening is far too sedate. Did Elgar Howarth conduct this piece, I wonder? The presence of his name on the front cover of the booklet is otherwise inexplicable.

Bax’s royal wedding fanfares can also be heard on a recently issued recording of the complete wedding ceremony in Westminster Abbey as broadcast by the BBC (Pearl GEM 0161). This is a fascinating document, not only for the music but also for the old-fashioned speech-style of the various divines, especially the Dean of Westminster, who practically chants his opening address. (How different from the nasal tones common in early 21st-century London; but perhaps these will seem quaint and genteel in another fifty years’ time.) The organist manages to hit quite a few wrong notes, and I can imagine Bax fidgeting in his pew during the interminable choral piece by Charles Wesley, though he must have perked up after the service when he found himself surrounded by young female fans of Noël Coward, with whom he had to wait for a car outside the Abbey. The two specially commissioned fanfares sound well, and it is interesting to note that the famous cricketer C.B. Fry (who was also renowned for having once been offered the throne of Albania) chose them as his outstanding musical impression of 1947 when approached by a music magazine at the time. Bax himself referred to the fanfares as ‘dreadful’ (though admittedly he was countering someone who was praising them to his face) and when asked for his own outstanding musical impression chose a performance of Vaughan Williams’s A Sea Symphony that he had recently heard in Dorking. I cannot imagine ever wanting to sit through the entire wedding broadcast again, but it is useful to have the fanfares available in their original context.

Copyright © Graham Parlett

Review by Christopher Webber

This sad addition to their mighty British Music Collection is a reminder of how little Bax Decca recorded in the 43 years between Malcolm Sargent’s Coronation March and Neville Marriner’s woeful November Woods – a performance in any case first issued by sister company Philips! That Decca needed this to pad proceedings out to a parsimonious 49 minutes is a shame. What we get is an unfocussed, short-measure CD with liner notes so ill-informed and ill-written that they would have disgraced a middle school essay. Master McGill, please note that Enchanted Summer does not feature a tenor soloist, but two sopranos – C minus and bottom of the class!

Although said notes do not hint at the fact, the opening Fanfare is the second and more substantial of two written for the 1947 Wedding of Princess Elizabeth. Recorded by a sub-par Philip Jones Brass Ensemble in 1970, it gets the disc off to a flat start. At 1:46 only completists will be keen to add such an unremarkable official trifle to their collection.

Next up is an arthritic limp through “Fagin’s Romp”, the witty march-scherzo from Bax’s music for David Lean’s Oliver Twist” film of 1948. Bernard Hermann and the NPO do much better by the “Finale”, given a appropriately dignified and stately send off. Here Bax utilized the main theme from the shelved tone-poem In Memoriam” (again, we’re given no clue to this in the notes). Now that fine earlier work has been salvaged, it’s instructive to hear the harmonic sophistication and consequent blurring of Bax’s great melody in its Dickensian reincarnation. Decca’s ripe 1975 Phase 4 recording is up front and personable, and with the deletion of the much more substantial suite on ASV, this just about makes a tolerable stop-gap until a much-needed complete recording appears. (Editor: To be recorded later this year with the BBC Philharmonic.)

A mild breeze wafts indolently through Marriner’s underpowered, undercharacterised November Woods, prime candidate for the least convincing Bax run-through ever released on CD. Philips’ pristine engineering only serves to emphasise some muddy orchestral textures in which you can’t hear the wood for the trees. The Academy of St Martins partially redeem the damage with their rapt, poetic playing in the magical eye of the storm; but altogether this pallid affair is no substitute for the awe-inspiring Boult on Lyrita, or Thomson on Chandos.

Matters improve with the two elderly recordings which fill out the CD. Both Boult’s early, mono Tintagel (1954) and Sargent’s Coronation March from the previous year receive clearer, brighter transfers with a wider dynamic range than their previous CD incarnations, on Belart and Beulah respectively; although in the case of Boult’s muscular, passionate Tintagel – first ever on LP – the string sound is wiry compared against the original vinyl.

The 1952 Coronation March, a frank rewrite of the Victory March based itself on music from the film score for the wartime film Malta G.C. (though the notes once again fail to mention this and manage to get the year of composition wrong!) has not been commercially recorded since this stalwart pioneering version under Sargent. Bax’s last orchestral work, it is an effective piece with a gently endearing tune in the trio section that bears a marked kinship to “Men of Harlech”. This seven minute March, and the strong Boult Tintagel – much more involving than his stereo remake on Lyrita – come part way towards redeeming this unsatisfactory and ill-designed rag-bag of minor Baxiana. As a suitable penance I suggest that now he has done with Vaughan Williams, Decca immediately ask Bernard Haitink to set down a cycle of Bax Symphonies, or at least the major tone poems!

Copyright © Christopher Webber