A Portrait of Sir John Barbirolli – on disc and in a new autobiography by Lady Barbirolli – both reviewed

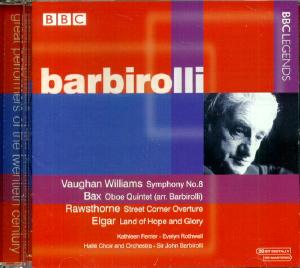

Barbirolli/BBC Legends: Vaughan Williams-Symphony No. 8; Bax-Oboe Quintet (arr. Barbirolli – Evelyn Rothwell, oboe); Rawsthorne-Street Corner Overture; Delius-On Hearing the First Cuckoo in Spring; Walton- Crown Imperial March (The Trumpeters & Band of the Royal Military School of Music, Kneller Hall); Elgar-Land of Hope and Glory (Kathleen Ferrier, Contralto, Hallé Choir); The Hallé Orchestra. BBCL – 4100-2

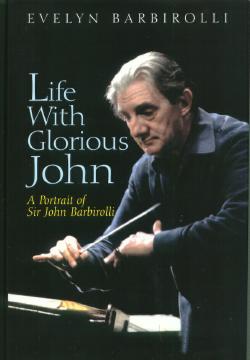

Life with Glorious John – A portrait of Sir John Barbirolli by Evelyn Barbirolli – Robson Books, 2002.

THE SIR ARNOLD BAX WEB SITE

Last Modified November 4, 2002

Barbirolli recordings were hard to come by when I first started collecting recordings in the late 1970s. My introduction to Sir John’s conducting came through a broadcast performance of Bax’s Tintagel. I remember listening to it transfixed and thinking it had all the fire and passion that Boult’s Lyrita recording lacked. I was sure that if Barbirolli’s Tintagel was that remarkable, his other recordings must be as well. Unfortunately, I soon learned that most of Sir John’s recordings were no longer in the catalog. I could still get the Elgar Cello Concerto with DuPre and the Mahler Fifth, but the Sibelius Symphonies, Vaughan Williams’s Fifth and Second, a good deal of Elgar and Delius, his Brahms, Beethoven and Schubert Ninth were all gone. I soon realized why when I began subscribing to the Gramophone and reading the Penguin Guide. The popular critical opinion of that time was that Barbirolli was too wayward a conductor and that in performances of Elgar, Vaughan Williams and the great German masters, Sir Adrian Boult’s recordings were preferred for their objective strength and straight-forward temperament. Critical opinion, it would seem, has changed a lot in 25 years.

Almost as soon as Sir Adrian Boult passed away in 1983, Barbirolli’s reputation began to surge. Many of his long out-of-print recordings such as Bax’s Third Symphony became available for the first time since their original release. Critics began to reevaluate their opinions on some of Sir John’s more controversial recordings such as his extraordinary Mahler Sixth and impassioned Elgar Second from 1964. EMI acquired the old Pye catalog and released most of Barbirolli’s Pye recordings on the short-lived Phoenixa label. Many of those recordings have since resurfaced on Royal Classics. The compact disc saw the reissue of almost all of Barbirolli’s back catalog and Dutton Labs, in association with the Barbirolli Society, has gone back and reissued many mono recordings dating back from Barbirolli’s New York years. Off-air recordings of several Barbirolli performances have surfaced and now the BBC has gone back to its archives and is giving us all the Barbirolli they’ve got. Almost everything Barbirolli recorded is now available and I feel safe in saying that Barbirolli’s reputation has never been so high. Sir Adrian, on the other hand, has not fared so well. Many of his recordings remain out of print but I’m sure it is only time until he is restored to his rightful position of one of the great conducting giants of the 20th Century.

Sir John’s memory has also been kept alive due in part to the on-going presence of his most extraordinary musical and personal partner, his wife Evelyn Barbirolli. During the great man’s centenary celebrations in 1999, Evelyn took part in all the BBC programs and was seen everywhere talking about her husband’s career and giving us reminiscences of what it was like to be married to such an extraordinary man. Thank goodness she was persuaded to record her recollections into a very entertaining autobiography that is now available from Robson Books. Lady Barbirolli’s memory is obviously as sharp as a tack and her text is filled with anecdotal details that really illuminate what it was like to live with such an emotional, warm-hearted and hyper-sensitive artist. It is the personal portrait that we get from her book. Michael Kennedy’s long out-of-print (but soon to be reissued) biography on Barbirolli is still the place to go for the comprehensive study on the Maestro’s career and analysis of his life. Lady Barbirolli’s book compliments Kennedy’s in that it gives us a working picture of what it was like to live with Sir John, day in and day out.

Sir John’s memory has also been kept alive due in part to the on-going presence of his most extraordinary musical and personal partner, his wife Evelyn Barbirolli. During the great man’s centenary celebrations in 1999, Evelyn took part in all the BBC programs and was seen everywhere talking about her husband’s career and giving us reminiscences of what it was like to be married to such an extraordinary man. Thank goodness she was persuaded to record her recollections into a very entertaining autobiography that is now available from Robson Books. Lady Barbirolli’s memory is obviously as sharp as a tack and her text is filled with anecdotal details that really illuminate what it was like to live with such an emotional, warm-hearted and hyper-sensitive artist. It is the personal portrait that we get from her book. Michael Kennedy’s long out-of-print (but soon to be reissued) biography on Barbirolli is still the place to go for the comprehensive study on the Maestro’s career and analysis of his life. Lady Barbirolli’s book compliments Kennedy’s in that it gives us a working picture of what it was like to live with Sir John, day in and day out.

None of the chapters are very long and the book can be read in one or two sittings. Lady Barbirolli’s writing style is conversational and straightforward. She does not dwell on unpleasant memories, nor does she avoid them. Her account of their New York years sets the record straight that Barbirolli’s relationship with the New York Philharmonic was warm and supportive but that his directorship was undermined by the New York press that had it in for him for reasons that had nothing to do with his abilities as a conductor. Her account of Sir John’s early years with the Hallé are even more fascinating to read. He encountered obstacles that most conductors would have found intolerable if not insurmountable but Barbirolli was a fighter and he built the Hallé into a much greater orchestra than it ever had the right to be considering what little financial support it received from the government. Fortunately, Lady Barbirolli discusses her own career and we get a sense of just how revered she was as an oboist. Living with someone as demanding as Sir John required her to give an enormous amount of herself and her career suffered as a result. She talks about this without any regret or bitterness. There were still opportunities to play and she frequently performed and recorded with Barbirolli and the Hallé. Indeed, the most fascinating chapter in her book is her account of watching her husband rehearse and record with the world’s great orchestras. He commanded great respect and was very formal with his players. He demanded absolute silence as he approached the podium and he could get very feisty with his players when they played below their abilities. But, she says, he was never cruel and he never singled out individual players for castigation. His players loved him and they called him “the boss” and he was sought out by all the great orchestras of the world. I got the impression from reading the book that while Barbirolli was treated as one of the truly great conductors of his time by the orchestras and press of the world’s great artistic centers like Berlin, Vienna, Boston, Paris, Chicago, New York (latter on), etc… he was taken for granted in England where he was viewed as the leader of a fine but provincial orchestra and was himself rather old-fashioned in his musical tastes and style.

For Bax fans, this book offers a few interesting anecdotes. She mentions a very amusing encounter with Vaughan Williams who tells the Barbirollis that he had just seen in a musical dictionary an entry for Harriet Cohen, Bax’s mistress, which said ‘see under Bax,’ “and this amused him greatly,” she said. Lady Barbirolli also tells us that Sir John had great affection for Bax’s music but was critical of it as well because he believed Bax had trouble knowing when to stop and “all too often a work could be spoiled because it outstayed its welcome.” She writes about Bax’s Quintet for Oboe and String Quartet that Sir John had played as a cellist in the Kutcher Quartet shortly after the work’s premiere in 1924. She said her husband “was always worried by Bax’s attempt to get too much out of the single strings by double stopping and divisi, which sometimes made the texture thick and un-beautiful.” While Bax was still alive, Sir John suggested adding a double bass part and rescoring some of the other string parts and Bax agreed although Barbirolli didn’t get around to it until the late 1960s, many years after Bax’s death. Barbirolli’s arrangement was first given at a London Promenade concert in 1967 with Evelyn as the soloist. They recorded the work in the BBC studios on 13 November 1968 and it is this performance that can be heard on a new BBC Legends disc of Barbirolli conducting British music.

There is no doubting Lady Barbirolli’s skill as an oboist in this performance but I don’t much care for the recording overall. Perhaps it has to do with the unflattering acoustic or Sir John’s heavy-handed conducting but this version of the Quintet sounds far more stodgy and thick than it does in Bax’s original arrangement. In fact, I had trouble recognizing the work in places, so distorted and ungainly did it sound to me. Based on this recording, I don’t think the Barbirolli arrangement is worth reviving although perhaps with a different conductor, it might work — but then what would be the point? Bax’s Oboe Quintet is really a perfect creation as it is and today’s players have no difficulties with the technical challenges it poses. I’d stick with the Nash Ensemble on Hyperion if you want to hear how this work should sound.

The rest of this BBC Barbirolli disc is quite interesting and is worth hearing even if it doesn’t present Sir John at the very top of his form in any of the works with the exception of a super-charged account of Rawsthorne’s Street Corner Overture. That performance has all the bustling energy that the 1967 live performance of Vaughan Williams’ Eighth Symphony lacks. Those familiar with Barbirolli’s premiere recording of this symphony made for Mercury/Pye in 1956 will find this later recording much more broad and relaxed. It acquires an appealing warmth as a result but a good deal of this works quirky edginess is lost and I miss it but it’s interesting to hear how Sir John’s interpretation changed over the years.

The Delius Cuckoo is also a little too heavy and slow for my tastes as well. While I normally prefer Barbirolli’s warmth and expressiveness in Delius to Beecham’s cool detachment, I find Beecham unrivaled in this little miniature and beside it, Barbirolli sounds terribly flat. I can imagine a few raised eyebrows at Barbirolli’s performance of Walton’s Crown Imperial March as well. It starts off beautifully but later on Barbirolli begins to mould the tempos a little too freely and the big patriotic tune threatens to collaspse under all the interpretive weight placed upon it. The ending is thrilling and the performance does have personality and I’m glad to have it. Kathleen Ferrier singing Elgar’s Land of Hope and Glory from the First Pomp and Circumstance March is thrilling as is the British National Anthem taken from a 1969 concert. Even a non-Brit like myself can’t help but be deeply stirred when hearing such a grand and heart-felt performance. I’m glad it was included on the disc.

Lady Barbirolli’s autobiography and the new BBC Legends disc compliment each other perfectly and I would encourage fans of the conductor to get both. Baxians will be disappointed by the recording of Barbirolli’s arrangement of the Oboe Quintet but the rest of the program should please all but the most critical listeners. There are finer and more polished accounts of these works available but nothing Barbirolli did was ever routine or uninteresting. I hope more such recordings become available including a riveting Vaughan Williams Sixth Symphony from Barbirolli’s 70th Birthday concert with the Hallé in Manchester. Talk about a classic! And do any of the master tapes of Barbirolli’s live performances of Bax’s Symphonies survive? There is a definitive Fourth in very poor sound that has been passed from collector to collector over the years but I wonder if a master tape survives somewhere — and what of his performances in the 1950s of the Bax Fifth and Sixth Symphonies? These are the Holy Grail of recordings for Bax fans and unfortunately, they will likely remain that way but one can always hope!

© Richard R. Adams 2002