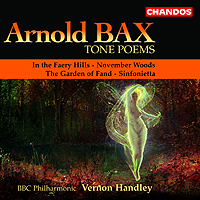

Vernon Handley’s new recording of Bax tone-poems on Chandos – Review by Graham Parlett

Bax: In the Faery Hills, November Woods, The Garden of Fand , Sinfonietta.

Bax: In the Faery Hills, November Woods, The Garden of Fand , Sinfonietta.

BBC Philharmonic, Vernon Handley.

Recorded in Studio 7, New Broadcasting House,Manchester , 20 and 21 April 2005 .

Chandos CHAN 10362.

Duration: 75:44.

Reviewed by Graham Parlett

Cicero used to claim in his legal speeches that he would refrain from mentioning his opponents’ faults; he then proceeded to list all the faults that he would not be mentioning. In similar vein I shall refrain from alluding to all the rave reviews that greeted Vernon Handley’s cycle of Bax’s symphonies; nor shall I mention its inclusion in the Gramophone editor’s 100 Greatest Recordings; still less that it was that magazine’s Orchestral Record of the Year; nor its choice as CD Review’s Disc of the Year on Radio 3; and as for the advocacy of political figures, the less said the better. Following on from the huge success of this milestone in the Bax revival, it was inevitable that there would be a follow-up, and in April 2005 the same forces assembled in New Broadcasting House, Manchester, to record this substantial programme of orchestral works (over seventy-five minutes’ worth).

In the Faery Hills, the earliest of Bax’s orchestral scores to be published, was completed at Glencolumcille in 1909 and was originally part II of his trilogy of tone-poems collectively called Éire, together with Into the Twilight and Rosc-catha. In a programme note for the first performance at Queen’s Hall under Sir Henry Wood, Bax wrote that it ‘attempts to suggest the revelries of the “Hidden People” in the inmost deeps of the hollow hills of Ireland ’. Handley’s no-nonsense approach to Bax is heard right at the outset: no pale loitering here but a down-to-business exposition of the opening material. The work begins with a ‘faery horn-call’, which appears to have been taken from Elgar’s incidental music to George Moore’s and W.B. Yeats’s play Diarmuid and Grania (1901). Handley also takes a very brisk and vigorous view of the Irish jig that follows, which depicts the faery revels, reminding us of Bax’s description of thesidhe (or ‘shee’, whence ‘banshee’) as ‘beautiful and often terrible faeries’. They are, as he pointed out, ‘very different from the lightsome folk of “A Midsummer-Night’s Dream”’, and throughout the score, by emphasizing the many sforzandi and other accents, Handley brings out this nasty side to their character. The climax of the scherzo in its published version (Murdoch, 1926) was changed from the 1909 original when Bax came to revise the work in 1921, and Philip Heseltine considered that the first version, which contains a rollicking trombone tune, was much better (Bax thought it too ‘vulgar’). It is hard not to agree with Heseltine, and I hope one day we shall be able to hear the original version, which is in the British Library.

The middle section, representing a song of human joy, which turns out to be the saddest thing the faeries have ever heard, has some sensitive solo playing from woodwind, harp, violin, and viola, and a fine, martial climax; the dance then resumes in high spirits. The two-bar transition from the very fast jig to the slow, quiet final pages is an awkward one: as Yuri Torchinsky, the leader of the BBC Philharmonic, remarked during a playback, ‘it’s like trying to stop a train’. However, the first violins manage this difficult feat with aplomb, and the Vivace codetta is neatly done. This tone-poem has now been recorded three times (Thomson on Chandos and Lloyd-Jones on Naxos being the rival versions), and all of them are very good in their different ways; we are lucky to have such a choice.

The second piece on the disc is November Woods, which was completed in 1917, the same year in which Tintagel was sketched. There are five other versions of this score available on CD conducted by Boult (Lyrita), Thomson (Chandos), Marriner (Philips/Decca), Lloyd-Jones ( Naxos ), and Andrew Davis (Warner Classics). Each has definite merits, especially, in my opinion, the Boult and Lloyd-Jones performances; but there is no doubt that Vernon Handley has conducted the score more often than anybody else, and he brings to it a lifetime’s experience. Everyone who was present at the recording session was bowled over by the performance, and I had the impression that the orchestral players themselves enjoyed playing this score even more than the others on the programme. It is certainly something special. At 20:30 it is the broadest performance on disc, but there are absolutely no longueurs or any suggestion of dragging. Handley always manages to choose just the right tempo, and the solo playing is of a high order throughout: that cello solo, for instance, just before the middle section, which ends on a high harmonic, has certainly never sounded better. The orchestra plays with total commitment and passion throughout, and after hearing such a stunning performance, nobody could be in doubt that November Woods is a masterpiece of tone-painting. No wonder Bax complained to Ernest Newman that ‘it was a terribly difficult piece to orchestrate’.

In an interview, Bax told Eamonn Andrews that The Garden of Fand was his favourite among his works, and it was the last piece of his own music that he ever heard performed. It also means a great deal to Vernon Handley, who chose it as his DesertIsland piece several years ago and whose daughter is named after the eponymous heroine. It is good to have his interpretation of it on record at last. The opening has a brightness and freshness that vividly suggest the flecks of light playing on the surface of the sea. The passage in which the small craft is cast up on Fand’s island comes off effectively, while the dance tune that follows is sprightly and well pointed. The transition from the fast music to the central section is wonderfully atmospheric, especially the magical bars for celesta over still string chords. Fand’s song of immortal love (which made Bax weep even as he wrote it) is very well shaped but without being too emotional. Handley makes less of the Largamente molto climax at letter N than other conductors, but the final cataclysm, with the mortals being drowned beneath the waves and the gods riding aloft in triumph, is overwhelming, while the soft closing page is most effective, with none of the key-clicking from the bass clarinet’s mechanism that so often buy pure phentermine spoils the effect.

There have now been seven recordings of Fand, of which I suppose Barbirolli’s is the most highly regarded, though Bax himself was pleased with Beecham’s performance, the only one issued in his lifetime. There is even a New Age disc entitled ‘The Garden of Fand’, performed by ‘Seven Pines’ on a ‘Church of Fand CD’ (FAND 001), which was inspired, we are told, ‘by love poems of Dermot O’Byrne. O’Byrne was better known as Arnold Bax, the great English composer who devoted his entire life to LOVE: NATURE: MUSIC & ALCOHOL’. (I have heard this disc and am glad to report that there is no musical connection with Bax’s score.) As far as the real Garden of Fand is concerned, Vernon Handley’s new recording will give pleasure for years to come and will, I am sure, help to counter Donald Mitchell’s description of the work as ‘a most embarrassing glimpse of one aspect of English musical culture’.

After three impressionistic scores from Bax’s earlier years, contrast is provided by the final piece on this disc, the Sinfonietta of 1932, composed between the Fifth Symphony and the Cello Concerto. Originally entitled ‘Symphonic Phantasy’ but always referred to by the composer as his Sinfonietta, it was never played during his lifetime. Around 1950 Christopher Whelen mentioned it in a letter to Bax, who replied that he had never thought the work was ‘quite up to the mark’ and had not tried to arrange a performance. When Whelen visited Storrington, Bax gave him the manuscript, nudging him in the ribs and saying ‘I don’t want this done, mind’. Ever faithful to the composer’s wishes, Whelen refrained from conducting it himself ― he was then Assistant Conductor of the Bournemouth Municipal Orchestra ― and only released it for performance in Bax’s centenary year (1983) when pressure was brought to bear on him from certain quarters, including Bax’s solicitors and the BBC. The unpublished manuscript was left to Dennis Andrews, who presented it to the Royal Academy of Music in 2003 to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the composer’s death. Vernon Handley gave the first performance with the BBC Welsh Symphony Orchestra at Llandaff in June 1983, and it was first broadcast on 23 December. A recording by the Slovak Philharmonic Orchestra under Barry Wordsworth is currently available from Naxos, coupled with the otherwise unrecorded Overture, Elegy and Rondo, but this new version comprehensively trounces it.

The work is in three linked movements, the first prefaced by a slow introduction, in which a motto theme is heard on strings that is to recur throughout, notably in the interludes that connect the second and third movements and in the final, triumphant march. I have always suspected that it was the first movement that dissatisfied Bax. It works very well until around 5:13, when the music seems to be treading water for a few pages until the change of tempo. Handley takes the opening alla breve faster than he did in 1983, and similarly the linking passages. The first movement ends with one of the principal motifs, a descending triplet, hammered out barbarically; a pity the sforzando at the start of the concluding timpani roll is lacking.

Wordsworth and the Slovak Philharmonic are at their best in the slow movement, which is similar in mood to parts of the Second Northern Ballad, though the BBC Philharmonic have the edge in sheer beauty of tone. Unlike most of Bax’s slow movements, this one lacks a big romantic climax, but this emotional restraint enhances its otherworldly atmosphere, and during parts of it Keats’s phrase ‘Cold Pastoral!’ wandered into my mind. The short interlude connecting it with the finale ends with expectant string chords, suggesting that the music is straining at the leash, ready to spring into action. The finale itself is precipitated by a solo kettledrum playing the rhythmic figure that is to be heard throughout the movement, but it sounds distant and feeble here. This is odd considering how well the timpani come across elsewhere; but once the rest of the orchestra enters and the movement is under way, it goes like the wind, much more exhilarating than in the Naxos recording (and in Handley’s 1983 performance for that matter). The movement is one of Bax’s most sustained pieces of fast, scherzo-like music, with no slow passages to interrupt its inexorable progress towards the climax, in which the motto theme is blared out by the brass. This is virtuoso playing of the highest order, with the orchestral players clearly revelling in the many opportunities to show off their technique. The antiphonal effect of the first and second violins answering each other around 2:08 justifies Handley’s placing of them on opposite sides of the orchestra, though elsewhere I sometimes felt that the violins sounded a little recessed. There then follows a coda, culminating in a brazen march, which is played for all it is worth and may remind some listeners of the similar passage near the end of the first movement of Winter Legends. The final flourish, which I have always thought too abrupt and inconclusive, comes off much more convincingly here than in the Naxos recording.

The black and orange booklet cover is quite striking, though the voluptuous fairy in the glade looks like the kind that Atkinson Grimshaw might have found at the bottom of his garden in Leeds rather than the feral species that haunts the Irish hills. The informative programme notes are (needless to say) by Lewis Foreman, and the recording is exceptionally transparent and analytical: Bax’s intricate harp parts have never sounded so clear, and you can hear the distinctive sound of the timpani roll played with pennies at 5:37 in In the Faery Hills, while the cellos’ col legno bars representing the cracking of branches in November Woods are startlingly vivid. Compared with the recordings in the cycle of symphonies there is perhaps a lack of warmth, with the strings sometimes sounding rather hard-edged. But the wind instruments come across very strongly indeed, which is especially beneficial in the finale of the Sinfonietta, with its many strenuous woodwind passages. The brass are splendid throughout.

Another magnificent achievement from the BBC Philharmonic team in Manchester , and no doubt another best-seller for Chandos. Warmest congratulations and thanks to everyone concerned, and especially to the incomparable Vernon Handley.

© Graham Parlett 2006