“Summer with Bax” – a Fresh Take on Reality – Review by Christopher Webber

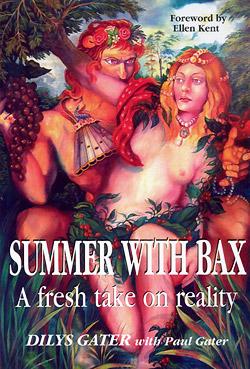

SUMMER WITH BAX

SUMMER WITH BAX

A fresh take on reality

DILYS GATER (with Paul Gater)

Foreword by Ellen Kent

Anecdotes, 2006 (£9.95)

ISBN 1-898670-09-9

9 781898 670094

review by CHRISTOPHER WEBBER

The Medium and the Message

Bax is a dead composer. Dilys Gater is a living medium. She and her husband Paul spent much of a recent summer communing with Sir Arnold, “in trance sessions that were fully documented and recorded.” The author pre-empts the prosaic objection:

People who claim to have no belief in the world of spirits, of whatever sort, are entitled to their opinion, but might as well stop reading here and now … the broader-minded will hopefully appreciate that mediumship is a gift, in the same way perhaps that an aptitude for music or painting is a gift – it puts one in touch with other, deeper and more meaningful truths that help to illuminate the banality of our everyday existence.

What, I wonder, draws so many of us off-centre types into the orbit of this particular composer? A musical imagination as elusive as it is strong? A personality at once simple and enigmatic? A life at once wild and approachably humdrum? For myself, I neither believe nor disbelieve in the “world of spirits.” Nor am I fired by the prospect of pursuing dear old Bax beyond the grave to squeeze out some last biographical oozings – a process which one may suspect such a shy, private man might have found at best wryly amusing, at worst a vulgar intrusion.

However, Dilys Gater’s manifesto caught my imagination; and as I read on I found myself drawn in by what she had to say. All creative work, especially that reliant on the word, requires an opening up of the artist to summoned worlds, more or less plausibly peopled in parallel with our own. As she defines it, Gater’s methodology as a medium has much in common with mine as an actor. She “tunes in” to a character bit by bit, over time, using a mixture of intuition and information – the difference is that she has a compliant spouse to do her research. Like an actor, she is not afraid to edit and refine the verbatim text, or to interpret in contemporary terms. So it is that her Bax talks not a mid-20th, but an early-21st language. He conjures effective and appropriate stage settings – meadow, walled garden, mountain shore, hotel bar, lighthouse – for each dialogue. He mixes his tenses between past and present. He is as humanly interested in avuncular banter with Dilys’ Paul as in articulating thoughts on artistic life and personal sensibility. He reportedly laughs a lot. He is, in a word, a plausible creation.

Whether Bax was spiritually present in any sense – mirror or mirrored – seems to me rather beside the point. Indeed the Gaters’ habit of adducing parallels between in-trance hints and verifiable facts from the composer’s life tends to diminish their work to a mere ghost hunt. Whether their matter comes from the beyond or not, their book is stimulating enough to stand up without mystic special pleading. They paint an engaging picture, touching on many aspects of our spiritual life, for which the focus on and through Bax provides a convincing medium. Its diverse preoccupations include musical form; love and “relationships”; that sad, wise contemplation of nature known to the Japanese as mono no aware; and the “dark shadows” of depression. Recurrent metaphors include sea and rain, mountains and diamonds. Whatever her method, Dilys Gater is a genuine poet in thought and deed, and this gives her work the same ring of truth we’d find in a well-written novel – or more likely Socratic dialogue – on her chosen subject.

Plato-Gater’s central theme, in so far as one emerges, is that despite the stifling pressures of present times we still have it in our power to live “on the edge”, to carve out (as did Bax) our own imaginative worlds. Whether this is courage or evasion, a denial of our social responsibility, is not a question with which Socrates-Bax has much truck. It is left to husband Paul, as the Opaque Pupil, to ask the damn-fool questions which would occur to most of us (“… what was it about the ‘Celtic Twilight’ that so captured his imagination when he was young?”) and he often finds himself the butt of Bax’s dry wit or running into of a more direct verbal cuff from Dilys. When Paul asks why his musical language was not more straightforward, Bax responds:

Who is to judge these things? Who is to say which language one should speak in? I speak in my own language, and the language that I speak in was learnt on the peak of the mountain, on the edge of the world. If I could have fallen off the edge of the world, I would have done it and I went to the very edge…

The contrary pull towards physical comfort and companionship is also examined poetically, through the prism of Bax’s relations with women, especially Harriet Cohen. Dilys has some sharp yet sympathetic intuitions about that infamous muse. At the climax of the final dialogue Bax describes a moment of revelation during a private play-through of a piano piece:

Dilys: … He’s thinking about her, seeing her sitting at the piano. Very grave, I think she was rather grave.

Bax: Every time she touched the key and played what I had written, and she’d look up and smile, and – that’s music!!…

You’ve seen my emotion. It was for different reasons on this occasion, but equally it cuts one to the heart when you look at the person – as I looked at her. It’s so painful. The experience is so deep and painful that it is almost impossible to suffer it. My emotions were like knives. They cut me into pieces – or they would have if I had let them – and I feel reluctant to meddle with knives. Perhaps my message is to show you how un-trivial the trivialities of everyday can be.

Despite the clunking last line, this metaphor-laden stream of consciousness – appropriate enough for a dialogue entitled To the Lighthouse – is characteristic of Gater’s technique at its most persuasive. By no means everything in the dialogues is at this level, but after a halting beginning the later encounters tap into a vein of eloquence which fairly sweeps one along. Here, for example, is Bax on music and the sea:

When you think about it, science tells us a lot, but in fact art tells us more. If you look at two bars of music, you are jumping perhaps from one universe to another between one bar and another, if there is a change of key. You can leap from one planet – or one galaxy, even, to another. This is what I find fascinating, the immensity of the small, as it were. A natural, or a sharp added to music, and suddenly you have created a world of chaos. This is what I found so interesting about the sea, because the sea does this. It’s there, always moving yet it goes nowhere, and yet the variations of every mood and every thing are encompassed in the sea –

…We come from the sea, everything comes from the sea…

Not an original thought, but well put. The five trance-dialogues are interspersed with clearly written reflections from Dilys alone, and a handful of pithy essays from Paul. The biographical ones are excellently done, encapsulating in about 10 pages flat everything we really need to know about the man himself. Indeed, the Gaters hope we will take the book as a continuation of Bax’s own Farewell My Youth, that famous picture of youth recollected in none-too-tranquil age. It uses the reflective mode effectively enough, not least in some of Dilys’ (or Sir Arnold’s) sustained lyric flights, but works best in the three-cornered dramatic forums, where lightning often strikes in the interplay between wife, husband and the character of Arnold Bax.

I confess to being surprised that Summer with Bax proves such an honest, perceptive and thoughtfully structured book. It is also in the main a pleasure to read. I don’t think the experience has left me much wiser about the business of Bax, though the Gaters have an intelligent and sensitive handle on their man; but it may after all have left me wiser about the business of being human. More damn-fool me – and more power to Dilys Gater!

© Christopher Webber 2006