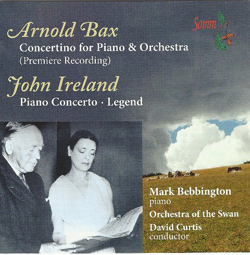

Premiere recording of Bax’s Concertino for Orchestra and Piano on Somm- Review by Richard R. Adams

Orchestra of the Swan

David Curtis (conductor)

Bax: Piano Concertino

Ireland: Piano Concerto and Piano Legend

SOMMCD 242

review by Richard R. Adams

Bax managed to summon all his creative powers one last time when he wrote his final symphony but following that work’s completion, the 56-year old composer more or less retired, “as a grocer”, as he was fond of saying and it’s true that none of his later works are anything as ambitious or as personal as his sublime Seventh Symphony from 1938/39. He did manage to compose one great film score in the late 1940s (for David Lean’s Oliver Twist) and he wrote a very pleasing Piano Trio in 1946 that showed he hadn’t lost his grasp of form but his inspiration faded quickly in those years following the Seventh Symphony. Bax’s last major work is the Concertante for Left-Hand and Orchestra that he wrote for Harriet Cohen after she injured her right hand. This score is very slight compared with “Winter Legends” and the “Symphonic Variations” although it does contain a wonderfully romantic middle movement that showed Bax could still write a fine tune when the spirit moved him. Bax wrote another very charming tone poem for orchestra and piano called “Morning Song” as well as a few songs, piano pieces and one last tone poem, “A Legend”, but aside from “Oliver Twist” and perhaps the Piano Trio, little of what he wrote in his last year s can be numbered among his greater works. Now a new work has emerged that was started soon after he completed his Seventh Symphony and its existence prompts several questions – most notably why did Bax abandon the work before completing some of the writing and all of the orchestration and does it contribute at all to our understanding of Bax the composer from this later period?

Bax started working on his concertino for piano and orchestra in 1939 and he intended it to be smaller scale than his previous works in that form thus giving it the name “Concertino”, although in truth it’s not much shorter than “Winter Legends.” What prompted this score is still a mystery although it’s easy to imagine the idea came from Harriet Cohen rather than Bax as we know composition had became something of an ordeal for the composer. He got as far as writing out the piano part for the outer movements and most of the middle movement but he decided to put it aside when world events in 1939 left him in no mood to be writing music. It was left in manuscript form and was practically unknown until the great Bax scholar Graham Parlett looked at it and decided Bax had completed enough of the score to be able to finish it himself and produce something authentic. Graham started working on the score about five years ago and the results of his work can now be heard on this new SOMM CD with the Orchestra of the Swan led bravely by David Curtis and the fine British piano music advocate Mark Bebbington as soloist. The disc is coupled with John Ireland’s glorious piano concerto as well as his wonderfully evocative “Legend” for piano and orchestra.

It’s a very brave man who tries to step into the shoes of a great composer and attempt to complete his or her work. It’s rare that these “completions” turn out to be anything other than a hodge-podge of what could have been although there are a few exceptions such as Derrick Cooke’s completion of the Mahler 10th and Anthony Payne’s completion of Elgar’s Third Symphony. Bax has been remarkably fortunate to have Graham Parlett in charge of most of his reconstructions as there isn’t a scholar alive who understands Bax’s style so innately. Graham’s completions and orchestrations have almost all been successful, some spectacularly so such as the First Tamara Suite, the complete score to Oliver Twist and my own favorite, his spine-tingling orchestration of “On the Sea-Shore”. Based on those credentials alone, it’s obvious Parlett is more than capable of taking whatever Bax left and fleshing it out but even a great arranger can’t do much to improve upon a score that isn’t too strong to begin with. So, has Graham’s efforts on behalf of the Concertino been worth it? I believe the answer is a qualified yes although there’s no denying the Concertino is far from Bax at his best and it doesn’t take much imagination to understand why Bax may have lost interest in it. Nevertheless, there are several fascinating moments in the work that indicate Bax was still experimenting with sonority and form and it’s finer sections do make us regret that Bax had lost most of his inspiration to write music at this point in his life.

The opening of the Concertino is vintage Bax and Bebbington exhibits tremendous control in his handling of the ascending and descending arpeggiated chords that are beautifully supported by the orchestra’s small body of strings that still manage to create the mostly warm and luscious sound. It’s a very wistful and delicate opening to a work that later proves to be anything but delicate as the movement’s primary theme is a stern and rather turgid tune that requires Bebbington to pound his way through several pages of very dense chordal writing that doesn’t quite flow from what’s come before. Perhaps Bax would have thinned out the piano writing as well as varied the texture a bit had he decided to complete it but the problem is as much the tune that isn’t strong enough to sustain the heavy-handed treatment it receives. The scoring places heavy demands on the orchestra and unfortunately the stings sound just too thin in places to provide the necessary weight required to balance the heavy piano writing. The orchestration is Parlett’s and it sounds authentic and orchestra and conductor, David Curtis, are undeniably sympathetic to the material and make the most of what they have to work with. They sound carefully prepared and very enthusiastic but in places they sound underpowered.

The middle movement is by far the most interesting and successful of the entire work and also the movement that required the most intervention from Parlett as he did have to fill in some of the piano writing as well as orchestrate and edit. Nevertheless, it still sounds as though he had more promising material to work with as Bax provides us with a fine melody that foreshadows both the theme from the slow movement of the Left Hand Concertante as well as looks back to his tune from “A Romance” that he also uses as the basis of the middle movement of the Fourth Symphony. This movement is oddly compelling even though it too doesn’t quite hang together as it should. There’s a quite stormy middle section for Bebbington to show off his solo playing and here he’s absolutely brilliant. Curtis and his orchestra support him with all the finesse and sensitivity this music requires.

Unfortunately it’s a little more difficult to judge the merits of the final movement because it’s here that the Orchestra of the Swan sounds less assured in their playing The movement opens with a strangely jaunty theme that I believe is one of Bax’s least appealing and it develops into music that I’m sure Bax intended to be jubilant and celebratory but actually sounds plodding due to the way the players drag their way through it. There’s no denying this is a weak movement but perhaps it could sound more convincing with a more brilliant interpretation.

So the Concertino is something of a curiosity that is worth hearing, especially for it’s very effective slow movement, but I doubt it’s going to endear itself into the hearts of Baxians in the same way both the Symphonic Variations or Winter Legends have. I’m grateful to Graham Parlett for making the work available as it does give us a glimpse of Bax experimenting with his textures and trying to come up with something more ‘popular” and in this it anticipates the Left Hand Concertante, which is itself a flawed but ultimately more satisfying work. Bebbington, Curtis and the Orchestra of the Swan are all to be congratulated for their commitment and skill in bringing the Concertino to life.

The rest of the program is made up of two better-known and greater works by John Ireland. Bebbington certainly knows his Ireland and he plays the piano part with all the sensitivity you’d expect and his performance of the Legend is arguably the most haunting yet available. Curtis and his orchestra give very spirited and sympathetic support but again, I believe this music requires larger forces so I’d have to recommend Parkin and Boult on Lyrita for the Legend and Stott and Handley on Confer for the Concerto but those interested in a slightly more intimate approach to the Ireland while at the same time hearing some unusual Bax should definitely investigate this very interesting disc.