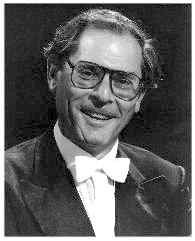

Robert Barnett Interviews Myer Fredman

Last Modified July 19, 1997

Myer Fredman is best known to Baxians for his outstanding recordings of the First and Second Symphonies. These recordings appeared on Lyrita in the early 1970s and for many of us they were our introduction to these great works. It’s astonishing to learn from the interview below that Fredman learned these complicated scores in only 10 days for they are so idiomatic and concentrated. The First Symphony is available on LYRITA SRCD.232 coupled with Raymond Leppard’s performance of the Seventh Symphony. Let’s hope Lyrita will soon reissue Fredman’s brilliant recording of the Second Symphony. Fredman has written a book on all aspects of conducting including technique, building a career, choosing repertoire and establishing relationships with orchestral musicians. His book is available through him directly. His e-mail address is given at the end of the interview. In the Interview below, Rob Barnett talks to Myer Fredman about his interest in Bax and other British music.

by Robert Barnett

Robert Barnett: Your Lyrita LPs of the Bax symphonies 1 and 2 are the cornerstone of many people’s introduction to Bax’s symphonies. How did the recordings come about?

Myer Fredman: I had recorded for Mr. Itter at Lyrita, a Symphony by Robert Still and another LP of Arthur Benjamin’s Overture to an Italian Comedy coupled with The Walk to the Paradise Garden by Delius (with Beecham’s orchestra, the RPO!!! As a result he phoned one day to ask if I knew any Bax, which at the time I didn’t and could I take on No. 1 at 10 days notice. He sent a score for me to consider and when I replied that I thought I could learn it in the time, he immediately responded with “what about the 2nd while you are about it?” In for a penny – in for a pound I thought so we recorded them with only five sessions for both! Neither Symphony was familiar to the LPO and I recall that the first movement of No. 1 took a lot of time for us to find the Bax idiom. As a result, the actual takes of the last two movements of No. 2 were recorded after just one read through because time was running out.

RB: Ken Russell Productions Ltd was supporting the recordings. Did Mr Russell attend any of the sessions or play any decisive part in the process?

MF: He did not attend the sessions and the only contact I had was when I went round to see him at his home in Holland Park and discovered how much he knew about Bax which was considerable. I asked him about Elgar’s Powick Quadrilles etc which he had just recently used in his Elgar TV Programme and, in due course, he sent me some of the manuscripts to look at.

RB: What was your reaction on seeing the scores of Symphonies 1 and 2?

MF: At the time I was more concerned with the necessity of trying to learn them in 10 days rather than attempting to assess them dispassionately but I hadalways been curious about his music and knew Tintagel and some of the songs. I had alsoread his literary works and I was very much an enthusiast for that whole period of English music, hence my curiosity about Havergal Brian also which later bore fruit.

RB: How do you rate the first two symphonies within Bax’s output and in the context of British music and internationally in the context of music of the 1920s and 1930s?

MF: They are marvelous in their different ways and in some ways the best of the seven although No. 3 is strong and tender also. As much as I love these works, the music of Vaughan Williams and Walton somehow overshadowed Bax and then Britten came along so that Bax was pushed even further into the background – quite wrongly in my opinion. What with the 2nd World War and his death not long after, his music has never really taken hold until perhaps now as a direct result of our pioneer recordings at that time.

RB: Symphony No. 1 has always seemed rather brutal and violent. What did you think of the piece?

MF: The second movement with its evocation of a ruined monastery is very striking although I was unaware of its extra-musical background at the time. The Irish rebellion certainly would account for a lot of its violence and the atmosphere of the ruined monastery.

RB: Symphony No.2 is amongst my favourite Bax scores. It has some stunning themes. What is your view?

MF: I agree. It’s a vast pagan land or sea-scape and the subtle lyrical rhythm of the slow movement is very beautiful indeed followed by the tumultuous last movement and then ending “with all passion spent”! To think that it was commissioned and first performed by Koussevitsky in America but never followed through!

RB: Do you detect the influence of other composers on Bax in these scores?

MF: Bax for me is a quasi-synthesis of the strength and grandeur of Elgar, the “pastoral” introspection of Delius, the orchestral brilliance of Debussy and Ravel yet with a harmonic language which is distinctly his own. My main criticism is that he couldn’t leave well alone sometimes but had to go on varying a theme, its harmony and structure and got occasionally got bogged down as a result. Also, in some of the other works, the themes themselves don’t always seem to have strong enough personality but are camouflaged in his orchestral virtuosity, (unlike Debussy and Ravel, for example, whose orchestral prowess always matched their subject matter).

RB: Are there other Bax works you have conducted or would like to conduct? I think you may well have conducted performances of Fand for Radio 3?

MF: I conducted a BBC broadcast from Manchester of The Garden of Fand which is a splendid work and In The Faery Hills with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra for a broadcast here. It is a most delicate work but as far as I can tell the ABC lost the tape somehow! I have conducted the Overture to a Picaresque Comedy which is well worth reviving but some of the other orchestral works proved to be disappointing when we played them through. I understand that The Morning Watch is very good but I have never seen a score or even heard a performance. Chappell’s lent me a manuscript score once of his Four Variations which I liked very much and if I remember correctly they were scored for strings and harp only.

RB: Are you familiar with the scores of the other symphonies apart from the first three?

MF: Yes, I have looked at all of them because I found quite a number of his scores (including a cello concerto) quite by chance in New Zealand when I was there recording a Britten and a Delius CD for Naxos. Apart from No. 3 I have not had an opportunity to conduct any of the other symphonies. Concert managements both in the UK and in this part of the world fight shy of programming Bax because of insufficient box-office appeal despite great interest by record buyers who are a different breed altogether from the concert going public.

RB: You have recorded the Symphony No. 3 in Australia . How did that recording come about?

MF: I can’t remember how the Bax Third recording came about but it was a fluke and the recording was deleted from the catalogue fairly early on for the reasons mentioned above. According to a press review that I still have, the recording was issued on ABC Records (L38227 and cassette C38227) but it seems to have been forgotten although not lost I hope even though I have not seen it advertised or in the ABC shops since we recorded it. The LP sleeve mentions copyright 1984 ABC records and issued by Festival Records Pty. Ltd. Australia under licence so we must have recorded it some months or a year before. It was recorded in the old ABC studios in Chatswood, Sydney which was a dreadful place to work in and the orchestra was pretty low in morale at that time (it is infinitely better now). They responded to it as yet another studio recording to fill out their working week. It has never been programmed in a concert and there seems no prospect of a CD reissue.

BR: What is the reaction of orchestras to Bax’s music.

MF: At the time of the two symphonies in London with the LPO there was great curiosity and I remember so many players came into the production booth with me to hear the takes . Initially in Australia there was some indifference for the reasons mentioned above but there were still enough interested players to spur one on. Now there is a vastly improved atmosphere thanks to great changes in the orchestral administration.

RB: If you were recording the Bax symphonies now would you want to make any changes in your approach to them?

MF: I would love an opportunity to re-record them after this considerable period of time (27 years!) and no doubt certain things would come out differently but it’s extremely unlikely that the opportunity will come along. At the time of the Britten/Delius recordings in New Zealand , Naxos said they wanted me to work my way through the entire Bax orchestral repertoire but that project was scrapped for some unaccountable reason.

RB: You have also been involved in various performances of music by Eugene Goossens.

MF: The Apocalypse recording came about in a round about way. Goossens himself had given its first (and only?) performance in the Sydney Town Hall and there are still musicians who took part who greatly revere Goossens as their musical mentor. The leader of the SSO, Donald Hazlewood who is just about to retire, Joan Sutherland who sang as a student under him in his opera, Judith, and Geoffrey Chard all speak of his inspiration discipline and vitality. I met him once in London after his return but he was by then a shell of the man he had been due to the machinations against him. Carole Rosen’s biography gives a very good insight into that episode. Anyway the ABC’s fiftiethanniversary was coming up, so one of their music producers had the brain-wave to have the very dilapidated manuscript of Apocalypse re-copied at great expense and asked me to conduct the performance. The work calls for a choir of vast proportions outnumbering Mahler but the biggest and best choir we could muster was the Philharmonia with only 200 or so members so volunteers were called for from the smaller (and less capable) choirs in the Sydney area. The ABC also intended making a proper studio type recording after the event but I had doubts as to whether the choral contribution would be of a sufficiently high standard for such an undertaking. Having booked the Sydney Opera House Concert Hall to do both the concert and the later recording they persisted with the idea right up until two weeks before the concert and only then agreed not to record it but they would do a recording of the live concert instead. Therefore I was asked what would I like to record with the large orchestra and the Concert Hall and Organ at my disposal? At that time, Vaughan William’s Job which is a favourite of mine only existed on the old Boult recording and the ABC eventually capitulated. Incidentally the music balance producer for both the Apocalypse and Job was none other than David Harvey who had worked on Bax 1 and 2 with me in England years before. I am very pleased with the Job recording and there is now a possibility that it might be released commercially. We discussed with Robert Helpmann the idea that he should speak William Blake s lines that preface each movement but the idea didn’t come to fruition. A year before the Apocalypse performance, a baritone had been engaged for the main role but there was a contractual mix up and only a few weeks before the actual performance a substitute had to be found who could learn such a long and difficult role in double quick time. Grant Dixon, a deep bass was eventually persuaded to take it on and sweated with me for a number of weeks on mastering the score which called for a high tessitura. The young Greg Yurisich who is now making a great career in Europe was the voice of God and the cast also included Ron Dowd just before he retired. During the performance, the baton flew out of my hand at the same point in the score as had happened when Goossens himself conducted it and later Rene Goossens, his daughter, presented it to me as a memento. This episode is also described in Carole Rosen’s biography. The LP recording of the live performance came off fantastically well. Musically the writing is perhaps too eclectic for our ears now with its mixture of Hollywood oriental and other musical sources but the orchestration is brilliant. Incidentally a few years ago I conducted an ABC Messiah using his orchestration which had been commissioned by Beecham and scored for 4 Horns, Full Brass, Harps, Bass Clarinet and a large percussion section with cymbal clashes during the Hallelujah Chorus. Great fun and loved by the audience (but not the purists!) That is all the Goossens I have done apart from a beautiful little tone-poem, By the Tarn.

RB: Is there any chance that the Apocalypse recording will be issued on compact disc?

MF: Perhaps, who knows. The ABC are now trying to capitalise on their archives so they might release a CD of it ditto my Vaughan Williams Job and his Partita for Double String Orchestra and the very powerful Respighi Dramatic Symphony.

RB: Were you able to give any concert or radio performances of any of these symphonies?

MF: Only broadcasts of the recordings which are still put to air regularly.

RB: Arthur Benjamin’s Symphony has now been recorded by an Australian orchestra. Have you had any involvement in Benjamin’s music?

MF: My involvement with Arthur Benjamin was originally as Chorus Master for the New Opera Company’s performances of Tale of Two Cities at Sadlers Wells then my recording of the Italian Overture for Lyrita. In Australia I recorded his opera The Prima Donna for the ABC again with David Harvey producing. Incidentally are you aware of my two Naxos CDs? On one, Britten’s Sinfonia da Requiem and the American Overture are included and Delius’ Paris, Brigg Fair and Eventyr on the other. We recorded them in a hall just outside Wellington in New Zealand in freezing cold weather and with car noises all the time outside. The NZSO is a very good orchestra consisting mainly of young Americans who had never played any of these scores before!!! The producer was Murray Khouri, himself a New Zealander who had been Principal Clarinet with the LPO when I recorded the Bax Symphonies and who played under me many times at Glyndebourne. He also is a great Baxian!

RB: Have you seen Richard Adams’ Bax web site?

MF: Just after buying this computer I stumbled across Richard’s web site which was a bit of a surprise to a novice nerd like me and even more to come across my name there as well. I am sure that the efforts of the BMS, Ian Lace and Richard will bear fruit on Bax’s behalf as musical tastes begin to swing towards this fascinating composer. I would willingly come over to further the cause if any opportunity arose.

RB: Your name is also associated with Havergal Brian’s music. How did that happen?

MF: I was quite active with Havergal Brian in the 60s and early 70s before coming to Australia . I am in fact one of the Havergal Brian Society’s Vice-Presidents. I had always been curious about this composer after reading Nettel s “Ordeal By Music – Music in the Five Towns” because my wife hails from Stoke-on-Trent . Then one day I read an article in The Times about HB and that he lived in Shoreham , Sussex . At that time we lived in Tunbridge Wells as it was convenient for Glyndebourne where I worked from 1959-1974 and as Shoreham was not far away I went down to see him on a number of occasions and he also wrote to me. When I asked him where he had studied composition, his reply was that he used to walk to Manchester to listen to Hans Richter and the Halle and that was about it! The letters I received from him I have recently sent to the Havergal Brian Society as they have requested such memorabilia. He came to Glyndebourne as my guest when I was conducting Werther which he enjoyed very much. HB thought my name was Marty Feldman! I am very friendly with his son Pat who lives inretirement in Norfolk . He invited me to Maida Vale Studio 1 for the recording of his Violin Concerto with Ralph Holmes and that is how I met Robert Simpson who then asked me to conduct some HB for broadcasts and I conducted some premiere performances and premiere recordings of some of his symphonies. The Lyrita recordings came about as a follow-on from the studio broadcasts when I suggested the idea to Mr. Itter who found the money somehow but unfortunately he couldn t find any more money to record some of the other studio broadcast recordings. I remember that the LPO literally got off the plane from China (jet-lagged) and came straight to the BBC studio to rehearse them for the very first time. I have no idea as to whether my studio recording of Symphony No. 22 is still in existence and surprised that you are aware of it. I have a number of HB scores here including a vocal score of The Tigers! I did record one of the early Suites in Brisbane but only for a studio broadcast and I imagine that the tapes have been erased. I understand that there is someone in Australia (unknown to me) who wants to put on The Gothic with me conducting but can’t find the money which is not surprising! With HB not having much success early on,he must have composed in a vacuum as it were and so he didn’t have an opportunity tohear his works in the flesh which might perhaps have then influenced his actual writing of the orchestral texture. I remember that it was always difficult to get real clarity between the parts which, I feel sure, sprang from this lack of a critical faculty. The other problem for the conductor is, as with Bruckner, being able to discover the inner connection between one musical paragraph and another to produce an overall satisfying unity. Incidentally it is not commonly known that thanks to HB, Elgar’s Gerontius finally got a proper performance in England and that HB was also responsible for composing the vocal score of Vaughan Williams’ Sea Symphony. He was the spitting image of Bruckner!

RB: How did you come to conduct the first performance in modern times of Bernard Van Dieren s Chinese Symphony?

MF: As a boy I had many times read Constant Lambert’s “Music Ho” which whetted my appetite for this unknown composer who had been of considerable influence on a generation of English musicians. I had also read Van Dieren’s book “Down among the Dead Men”. Then John Woolf of the Park Lane Group asked me to conduct the first professional performance of Delius’ Fennimore & Gerda at the Camden Festival which curiously enough, Beecham had never conducted out of pique at Delius and Warlock’s criticism of Beecham’s British Opera Company and the producer (whose name I just cannot recall now) turned out to be someone who had been very much part of that circle. I asked him about van Dieren and he mentioned that his son lived in Tunbridge Wells (!!!!), in fact about three or four roads from where I lived so need-less to say I contacted him and he lent me various scores including some of Beecham’s Delius scores with his inimitable blue pencil markings. Amongst his father’s works was an unfinished Dance Symphony which apparently various composers, including Walton, had been asked to finish but turned down as being too difficult to complete. The scores were beautifully hand-written but in an incredible amount of parts rather like the Tudor Madrigalists, only for orchestra and then I came across the Chinese Symphony. It is a setting of the same poems that Mahler set for Das Lied von der Erde. Thanks to David Ellis at the BBC in Manchester we scheduled it for broadcast coupled with another forgotten work, Elgar’s Lux Christi. I cannot remember the date of the recording but it was in the old Milton Hall studios and the soloists were Vivian Townley, Enid Hartle, William Elvin, John Mitchinson and John Tomlinson (the present world-renowned Wotan). For this BBC performance of the Chinese Symphony I used the manuscript score that Warlock had copied and from which Constant Lambert conducted the premiere. The Chinese Symphony has some beautiful sections but also some rather turgid passages with, again, like HB, difficult to achieve a clear texture. Fine for broadcasting purposes using orchestral microphones but very difficult to balance with the singers in a concert hall. Van Dieren has a certain affinity with Delius but without his passion! I remember Spike Hughes telling me about a projected TV opera but then the 2nd world war broke out. The Elgar is a splendid work but, try as I might at that time, no one was interested in releasing it commercially. It does seem to be my fate to pioneer rare works and composers (e.g. Bax) and then other conductors come along to consolidate my spade work!

RB: What about other British music?

MF: I came to Australia to create the State Opera of South Australia in Adelaide in late 1974 and during my tenure up till 1980, I gave the Australian premieres of Britten’s Death in Venice , Tippett’s Mid-summer Marriage and Maw’s One Man Show. Before leaving England however in London I recorded for the BBC Van Dieren’s Elegy for cello and orchestra with Christopher Bunting coupled with Goossens’ By the Tarn and Constant Lambert’s Piano Concerto with David Wilde which is a brilliant work inspired I think by Duke Ellington. In Australia , I have conducted a Symphony by Edgar Bainton who had emigrated to Australia to direct the Sydney Conservatorium before the 2nd world war. To my ears, his music is a mixtures of his musical idols i.e. Elgar, Vaughan Williams and a little Delius although his Concerto-Fantasia for piano and orchestra which I recorded with Frangcon Davies is much better. I have a cassette of our performance. I think that he won the Cobbett prize with it.

Copyright © Rob Barnett

Myer Fredman has written a book on conducting which can be obtained from him directly by contacting him via his web page: http://mfredman.customer.netspace.net.au/ or his e-mail address; [email protected]