Bax’s early Symphony in F – Premiere recording on Dutton

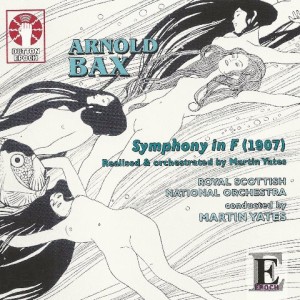

Arnold Bax: Symphony in F (realized and orchestrated by Martin Yates)

Arnold Bax: Symphony in F (realized and orchestrated by Martin Yates)

Royal Scottish National Orchestra; Martin Yates (c.)

Dutton CDLX 7308 [TT=78:28]

[rec. RSNO Centre, Henry Wood Hall, Glasgow, 15–16 August 2013. Producer: Michael Ponder. Sound Engineers: Dexter Newman, Dillon Gallagher. Editor: Richard Scott]

Review by Graham Parlett, who writes about the origins of the work, Richard R. Adams, who writes about the performance and recording.

The Symphony in F was Bax’s earliest attempt at writing a piece in this form, preceding the completion of his first official symphony by fifteen years, and is his longest composition apart from the unorchestrated ballet Tamara. The work is referred to in Farewell, my Youth (pp. 37–8 of the first edition), in the chapter describing Bax’s second visit to Dresden in Saxony during the first three months of 1907, when he was twenty-three years old: ‘I was engaged upon a colossal symphony which would have occupied quite an hour in performance, were such a cloud-cuckoo dream to become an actuality. (Happily, it never has!).’ In March, after completing Fatherland (tenor, chorus and orchestra) and the song ‘The Fiddler of Dooney’ (W. B. Yeats), Bax left Dresden with ‘a tall, calm-eyed Scandinavian girl’ (identified by Bax’s sister, Evelyn, as Dorothy Pyman), and the short (or piano) score of this symphony was finished a few weeks later, on 3 April. Although the work appeared in early lists of Bax’s music, such as the 1914 edition of Grove’s Dictionary (as ‘Symphony in F minor and major’), the composer never orchestrated the work, and after his death the manuscripts of the first two movements were given by Harriet Cohen to Colin Scott-Sutherland, while the third and fourth movements were handed to Professor Aloys Fleischmann, to be kept in the Bax Memorial Room, University College Cork, which was opened by Vaughan Williams in 1955. When the Memorial Room was denuded of its Bax material in the 1980s, the two movements were re-housed in the college’s Boole Library, and later on Mr Scott-Sutherland sold his manuscripts to the library in order that all four movements of the symphony could again be kept together.

I have owned a photocopy of the complete piano score for many years, and in 2008 I decided to transcribe it on to Sibelius with a view to seeing whether any of the movements might be worth orchestrating, and a copy of this transcription was later given to Martin Yates. Having studied the score very closely, I came to the conclusion that it would not be worth the time and effort, a decision that I am now glad I made since Yates has done a very much better job than I could have managed. Bax left very few indications of his intended instrumentation in the manuscript, and it may be objected that Yates’s orchestration is much grander and showier than the kind of style that Bax himself would have employed if he had done it himself in 1907, by which time he had written at least six orchestral works, of which only the Variations, Cathaleen-ni-Hoolihan, and A Song of War and Victory are extant; but the result is undeniably striking and effective. Unlike Anthony Payne and Elgar’s Third Symphony, Yates was able to work from a virtually complete piano score, the only missing bits being a few bars in the finale where the left-hand part is blank, though these were easy to fill in. Anyone interested in Bax will be grateful to him for enabling us at long last to hear the work and to understand how it fits in with the development of his musical style at this period of his life, before the tone-poems and symphonies for which he is best known.

© Graham Parlett 2014

If Bruckner can have his symphonies in 0 and 00 then why not Bax? While Spring Fire may not be included among Bax’s numbered symphonies, the composer did identify it as a kind of “freely-worked symphony” albeit one with an explicit program and this has caused some in recent years to refer to it as his Symphony No. 0. Bax wrote an even earlier symphony while he was studying in Dresden (1906-07) and it’s believed this was his first attempt at writing in a large scale symphonic form. Evidently this exercise was inspired in part from his having heard the first two movements of Mahler’s Sixth Symphony and the entire Fifth Symphony of Bruckner (Schalk edition) in and around Dresden as well as Strauss’s Salome. Bax evidently realized that what he completed in piano score was just too ungainly and didn’t warrant the effort of orchestrating it. Luckily, he didn’t destroy the manuscript as it was passed down in various collections and ultimately found its way to the Cork University Library along with many of Bax’s other original manuscripts. No attempts were ever made to orchestrate the work until the ambitious Martin Yates took a look at it and determined the score had some potential. His efforts to orchestrate and edit the work were completed last year and a recording was made soon after for the Dutton Label. This new recording shows Bax’s early symphony to be a work of huge ambition and imagination but one that doesn’t quite sustain its length. It does give indication of the musical influences on Bax at that time — many of which the composer would discard soon after.

As recorded here on Dutton, the symphony lasts some 77.30 minutes. It easily the largest-scale work Bax ever attempted aside from his uncompleted ballet, Tamara. It’s in four movements including a rigorously paced and developed first movement, a romantic second movement marked Andante con molto, a waltz-like third movement and a rather overblown fourth movement. I have no idea what Bax would have made of Mr. Yates efforts to resurrect this score but I’m certain he would have approved of the orchestration. It is masterfully done and it does allow us to assess this very early work on its own terms.

So can it be said that Bax’s early Symphony is something more than a curiosity? For those of us who love Bax’s music for its visionary use of harmony and counterpoint and brilliant way with form, this symphony will come as something of a shock. Despite its enormous size, it’s also one of the most traditionally structured of all his works. There are some fantastic elements to much of the music but its closer to the world of Bantock and Glazunov than to those composers whom we associate with mature Bax like Delius, Elgar and Sibelius. When listening to this early English symphony, we have to remember that it predates the symphonies of Elgar or Vaughan Williams and in truth it sounds much more Russian than anything we would identify as British sounding today. The two most interesting and original movements are the second and third and I can see a case being made for stand-out performances of the second movement even though here we are still quite a ways from the startling originality of those early tone poems like In the Faery Hills, Into the Twilight or Christmas Eve in the Mountains.

I’m afraid one of the reasons this symphony fails to impress has more to do with the recording. A symphony like this must be played with all the power and force that a great symphony orchestra can bestow upon truly mammoth works like the symphonies of Mahler and Bruckner. While the Royal Scottish National Orchestra plays very well for conductor Martin Yates, I get more of a sense of caution than inspiration in the performance. The playing isn’t helped by the acoustic of the Henry Wood Hall in Glasgow that drains all weight from the strings and emphasizes the brass. Dutton is an extremely fine label but I do wish they’d find another venue to record the great Royal Scottish National Orchestra. Naxos had similar problems with their recordings in Henry Wood Hall although Chandos seems to have understood how to make that acoustic work – or do they record someplace else? I realize I’m being churlish to complain about the recorded sound when this was such an important and brave endeavor but as doubtful as my hope may be, I do hope this symphony will be recorded again someday in a manner that does full justice to its size and complexity and in a performance that really catches fire.

So, is it worth hearing? Well…for anyone who cares at all for Bax or British music in general, the answer is an obvious yes. It’s startling to hear what the young Bax was capable of even before his older compatriots had written their first symphonies and also to see how within a very short time after completing the piano score, Bax was looking elsewhere for his inspiration and within a year or two was writing those early masterworks that mark him out as one of the most adventurous and challenging composers of his time and for that I have to thank Ireland and William Butler Yeats!

© Richard R. Adams 2015